Chronic Abdominal Pain-A Remarkable Case

Chronic Abdominal Pain in Review

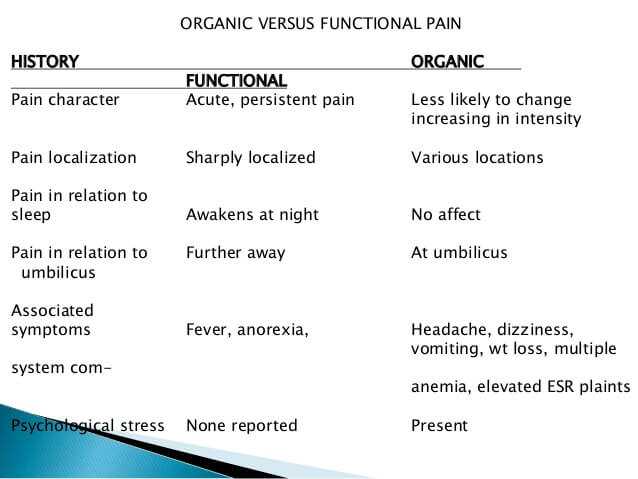

Chronic abdominal pain (CAP) occurs in about 2% of American adults. The majority of these patients are female. Of all people that have CAP, the medical literature estimates 10% to be due to an actual physiologic abnormality and 90% to be due to “functional” causes (psychiatric). This article will be focused on a real case of chronic abdominal pain…a remarkable case indeed.

In my practice of chronic pain management, I had the occasion to attend to people who have CAP. CAP is defined as abdominal pain that persists continually or intermittently for 3 or more months. It is usually identified in patients 5 years of age or older.

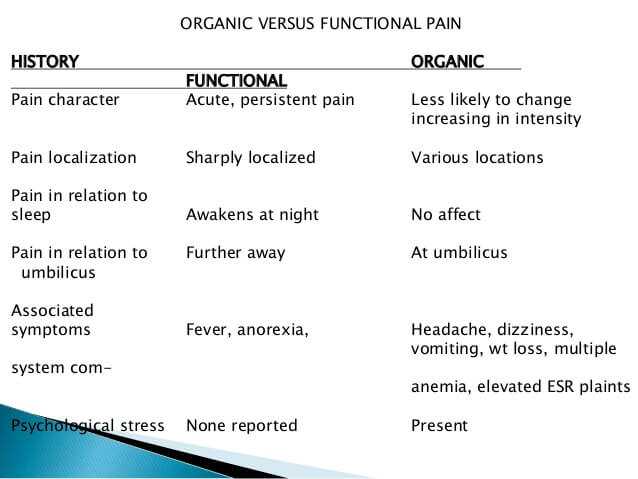

The abdomen has the largest number of organs of any portion of the human anatomy. The symptoms that suggest dysfunction of an abdominal organ can be quite vague. Furthermore, the same symptom can relate to dysfunction of any number of organs located in the abdomen.

The ability to diagnose abdominal organ dysfunction has improved over the years. With the advent of excellent non-invasive diagnostic testing, the need for an exploratory laparotomy (surgically exploring the abdominal cavity) for chronic abdominal pain has decreased.

Abdominal CT Scanning, Abdominal Ultrasound, Abdominal MRI, Endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus-stomach-small bowel-large bowel-biliary system, and HIDA scanning have all resulted in increasing the likelihood that a cause of abdominal pain can be found without surgical exploration.

Yet and still, some cases of chronic abdominal pain defy detection. There are a number of causes of abdominal pain that are primarily due to an abnormality of the contraction of the tubular structures located within the abdomen. This type of abnormality may not be detected on the usual non-invasive testing for chronic abdominal pain. It may also not be detected with surgical exploration of the abdomen.

Most non-invasive testing of the organs located in the abdomen test for a structural cause for chronic abdominal pain. This is actually one of the major pitfalls in chronic pain management. As there is no present way to objectively measure pain in a person, Doctors rely on structural evidence to support whether there is organic pain being reported by the patient. What if the patient is experiencing organic pain that is caused by a disorder that does not result from a structural cause?

Those patients are often mislabeled as “drug seeking” or “attention seeking” and may be disparaged by their Doctor. There are a large number of people with chronic pain who do not have a structural cause for their chronic pain. It is imperative that Doctors discipline their minds to the possibility that the person who is complaining of pain may have a non-structural cause for it.

The Case Of M.K

The following is a real case that was referred to my practice of chronic pain management. I have changed many details about the case and am only disclosing the initials of the patient in order to protect their privacy.

M.K Presents to My Office

M.K. came to my office with a complaint of abdominal pain for many years. The pain was continuous, increased and decreased throughout the day, was made worse with a meal, located in the right upper quadrant, and was associated with constipation alternating with diarrhea.

M.K.’s pain had totally taken over his life. He was in danger of not being able to perform his work duties (he had an office position in a local non-profit organization). His marriage and family relationships had also been severely affected by the chronic abdominal pain. His social life was also curtailed as he could not predict when the pain would intensify.

He had been seen and treated by a number of pre-eminent Gastroenterologists, General Surgeons, General Internists, Family Physicians, and many other specialists related to his many conditions.

In addition to CAP he had Central Sleep Apnea, GERD (gastro-esophageal reflux), Asthma, Hypertension, and Chronic Headaches from Occipital Neuralgia. He was on chronic oxygen therapy, a host of medications, and had an anthology of surgical procedures that had been performed on him.

Most notably, he had his Gallbladder removed for presumptive Cholecystitis (a gallbladder malfunction). Despite the removal of his gallbladder, he still had chronic right upper quadrant pain. M.K. brought all of his medical and surgical reports with him for his first office visit. He had cataloged and indexed all the data for me. I have never had any patient so prepared for their office visit.

None of his previous Doctors treated his pain effectively. No doubt the other medical conditions were the reason for their reticence.

It took me at least an hour to interview and examine him. We then poured over his records. He had the most extensive and academic work-up for his CAP I had ever seen. There did not seem to be any major deficiencies in his work-ups and treatments. I agreed with nearly all the of his other Doctors management.

A Pragmatic First Approach to M.K.’s Abdominal Pain

I was uncertain as to why he still had right upper abdominal pain. We agreed together to take a pragmatic approach to his pain management. We began with an opioid that could be given transcutaneously (Duragesic). I preferred this mode of delivery as it was gradual, did not require gastro-intestinal absorption, and had not been tried before.

M.K. returned every 2 to 4 weeks for re-evaluation of our pain regimen. Each time I increased the dose of the Duragesic he had temporary relief, only to find that the pain returned after several days. Furthermore, the Duragesic was worsening his Central Sleep Apnea as opiates can have this side effect in high doses.

I knew I couldn’t advance the dose of the Duragesic any higher. M.K. was having less pain but was more fatigued on it…his already unstable sleep cycle was being affected adversely by the opioids. I had to tell M.K. the bad news, that we had to stop increasing his dose of medications. He was understandably upset as this was the first time in years that he was having some relief.

I was perplexed what to do next…if anything. M.K. and I agreed to “freeze” his medication regimen at the present dose. I told him I would be doing a literature search to see if there were any innovative diagnostics or therapies we could try. My next move would be an academic referral to Johns Hopkins University or the University of Pennsylvania. I wasn’t optimistic that they would have any recommendations different from what had already been done.

A Work of Providence

In the days that M.K. had come into my practice, I used to work as an Emergency Room physician weekend nights in a local community hospital. I had been doing so for nearly 10 years when I met M.K. I liked the excitement of the ER…but not enough to work fulltime.

One given night a 20-year-old female patient was brought emergently to my ER in shock. According to her family, she had been having fevers for several days but had refused to come to the ER for evaluation. She was unconscious when I came to her bedside in the ER. I noticed she had a long term intravenous tube placed under her collar bone (called a Hickman Catheter).

People with long term intravenous lines often develop infections related to their use. I needed to remove the line and culture the tip for infection. As I wrapped the line around my gloved hand to pull it out forcefully, the patient suddenly awoke and demanded I not do that. Evidently, the fluids and oxygen that we were giving her had revived her to a degree.

The patient related a story to me that she had Biliary Dyskinesia with severe abdominal pain and received an intravenous synthetic opiod agonist-antagonist called Nubain. The Nubain had changed her life for the better and she did not want me to stop it. I reassured her I would give her the Nubain through a “clean line” and needed to remove the infected line…she agreed. She also told me the name of her Doctor at the University of Pennsylvania who managed her Nubain.

As I wrote up the patient’s admission my mind wandered to the case of M.K. Could he have Biliary Dyskinesia? Would he benefit from a continuous Nubain infusion? I determined to call M.K. and ask him if he would be interested in pursuing this line of reasoning…he was.

I discussed M.K.’s case the following Monday with the gastroenterologist at the University of Pennsylvania who was supervising the woman’s case of Biliary Dyskinesia (BD). She had been part of a research study looking at ways to diagnose and treat BD. The study was closed to further patients. I would be unable to enroll M.K.

The diagnostic method the University of Pennsylvania (U of P) was researching for BD (measuring the pressures inside the biliary tree of the liver) was not available for routine use. The gastroenterologist running the study at U of P suggested that I had good evidence that M.K.’s case was BD and that I could proceed with that as my presumptive diagnosis.

Nubain was their medication of choice for biliary pain in the BD study as he believed it had less anti-cholinergic side effects than other opiods (this can make biliary pain worse). Perhaps this was why M.K. had only partial relief of his pain on the Duragesic.

A Difficult Transition

I called M.K. and scheduled him for admission to my affiliate hospital. The switch from his present opiod regimen would not be easy. Nubain has antagonistic properties to regular opiates so M.K. would have to be fully detoxed before I started his Nubain. Also complicating matters was M.K.’s Central Sleep Apnea, and the need to anesthetize him for placement of a Hickman catheter.

What I was attempting to do had never been done at our hospital. Furthermore, none of my specialty support colleagues had done this before. Even the pharmacy of our small community hospital did not have a supply of Nubain. Would the hospital administration allow me to do this for M.K.?

I planned to admit M.K. to the intensive care unit, consult a Pulmonary specialist to help with his Central Sleep Apnea, personally discussed the case with my favorite surgeon to place the Hickman under local anesthesia, and convinced the pharmacy to obtain the Nubain (which was exceedingly cheap).

We detoxed M.K. by giving him a continuous infusion of Ativan for sedation. All of M.K.’s previous opiods were discontinued while he slept on his Ativan infusion for 3 days. At the end of 3 days we started his Nubain infusion and stopped his Ativan infusion. M.K. woke up several hours later in the ICU and had his first meal in days.

Our first conversation in 3 days went like this (his wife was in attendance), “M.K. how are you feeling?” I asked. With the biggest grin you could imagine he said, “Doc, I have very little pain…it worked!” I discharged M.K. with the Nubain infusing by a portable pump. The next time I would see him would be in my office in several days.

A Miraculous Result

At M.K’s first post-hospitalization office visit his wife came with him. He was rating his pain a 3 out of 10 (the first time in years). He said, “Doc, I was intimate with my wife for the first time in 6 years. I don’t know how to thank you.” He and his wife both wept. I was exhilarated.

The case of M.K. has miraculous elements to it. Not all my pain management cases turned out so positively. A case of Biliary Dyskinesia may occur once in the career of a Pain Management physician. In my next section I want to explain to you a little about Biliary Dyskinesia.

What Is Biliary Dyskinesia ?

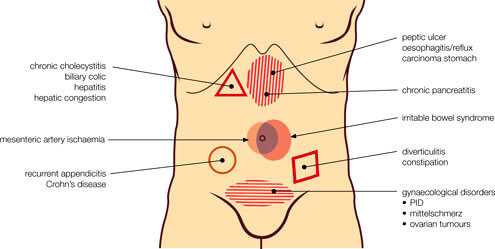

Biliary dyskinesia is a symptomatic functional disorder of the gallbladder and/or biliary system whose precise cause is unknown. It is a dysfunction of the contractility of the gallbladder and biliary tree. It will not be detected by structural evaluation of the anatomy and is a “diagnosis of exclusion.”

It is essentially a disorder of motility. It will often be found in people who have other disorders of gastro-intestinal motility.

What Is Are The Signs And Symptoms Of Biliary Dyskinesia ?

Biliary Dyskinesia presents just as any other cause of biliary colic (pain that crescendos and decrescendos):

- Episodes of right upper quadrant pain

- Severe pain that limits activities of daily living

- Nausea associated with episodes of pain

How Do You Diagnose Biliary Dyskinesia ?

BD is a diagnosis of exclusion which means other structural causes for the pain syndrome must be ruled out by the usual non-invasive diagnostic studies (a liver and gallbladder ultrasound for instance). The structural causes of biliary colic are much more common than BD. The Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional gallbladder/biliary disorders should be considered when attempting to discern BD. They are:

- Pain episodes that last longer than 30 minutes

- Recurrent symptoms that occur at variable intervals

- Pain that is severe enough to interrupt daily activity or lead to ER visits

- Pain that builds up to a steady level

- Pain that is not relieved by bowel movements, postural changes, or antacids

- Exclusion of other structural diseases that could explain the symptoms

- Other supportive criteria include: association of pain with nausea and vomiting, radiation of the pain to the infra-scapular region, and pain that wakes the patient in the middle of the night.

- Normal liver enzymes, conjugated bilirubin, and amylase/lipase.

When the gallbladder is still intact, satisfying the Rome III diagnostic criteria, the next step in diagnosis is a HIDA Scan. This scan utilizes a harmless radioisotope which concentrates in the liver and is secreted through the biliary system. A trained radiologist can then make calculations of how effectively the gallbladder contracts to propel the isotope into the small bowel (called a gallbladder ejection fraction).

A dyskinetic gallbladder will not contract well indicating a sluggish physiologic pattern. In the case of M.K. mentioned earlier, his gallbladder had been removed so this study would not be very helpful. Gallbladder pain can occur even without stones being present.

Patients with a gallbladder that has an ejection fraction less than 38% and satisfy the Rome III diagnostic criteria are considered to have BD. It is noteworthy that the HIDA scan must be performed without the patient taking medicines that can slow down the gallbladder contraction. A partial list of the medicines that can do so is as follows:

- Calcium channel blockers

- Octreotide

- Progesterone

- Indomethacin

- Theophylline

- Benzodiazepines

- H2 blockers

Carefully coordinating the HIDA Scan with a radiologist is very important. The HIDA Scan is best performed as an outpatient to limit the effect of hospitalization on the test (diet, sleep cycle, etc. that are effected with hospitalization).

What Is The Treatment Of Biliary Dyskinesia ?

Patients with an intact Gallbladder, HIDA Scan gallbladder ejection fraction of less than 38%, all other causes of right upper quadrant pain ruled out, chronic pain for at least 3 months, and that satisfy the Rome III diagnostic criteria, will be recommended to have their gallbladder surgically removed. Even then, 50-70% of patients only will have symptom relief.

That means that up to 50% of patients will not have symptom relief. Under those circumstances the only alternative for patients would be to have their chronic pain treated. This is what happened with M.K. He was in the 30 – 50% of people with BD that, despite having his gallbladder removed, continued with a very disabling chronic pain syndrome.

Summary Remarks

I have reviewed a remarkable case of chronic abdominal pain, the essentials of Biliary Dyskinesia, its diagnosis, and treatment options. I believe that there is a sizable number of people with CAP that suffer from this malady.

If you or a family member have CAP, it would be advisable that a methodical work-up be performed to rule-out the usual causes of chronic abdominal pain. If the work-up is unrevealing, then BD may need to be considered.

As with M.K., there is hope for relief of your chronic abdominal pain. As of the writing of this article, M.K. has been on a Nubain infusion for nearly 10 years. He is still obtaining relief with this therapy. I have since retired and he is managed by a new pain management physician who now has his first case of Biliary Dyskinesia.

I hope you have enjoyed this article. If you have further questions, please comment.

Wishing you joy and healing,

Facebook

Google+

Twitter

Pinterest

Reddit

Tumblr

Digg

Skype

StumbleUpon

Telegram

Pocket

WhatsApp

Email

Print

XING

Delicious

VK

OK

LinkedIn

I don’t know. Sorry. I’m just writing. 🙂

En la charla se habló de diferentes aspectos de la enfermedad mental crónica y s.