Alzheimer’s disease: a family illness

Alzheimer’s disease: the family experience

In the preceding articles, we breifly outlined the dilemmas Alzheimer’s families face in various phases of the Alzheimer’s journey. We described some ways in which the family can be understood as a system—as an identifiable entity that possesses a boundary, structure, and culture. And we examined the specific nature of Alzheimer’s disease—its origins and its effect on afflicted individuals.

In this article, we will focus on Alzheimer’s disease as a “family illness”—as an “invader” that disrupts and “disorganizes” long-established family routines, rituals, rules, roles, and relationships. And we will explore the nature of the adaptive, learning family system —its uses and its relation to Alzheimer’s care issues.

Let’s first consider Alzheimer’s disease as a family “invader.”

Alzheimer’s disease as invader

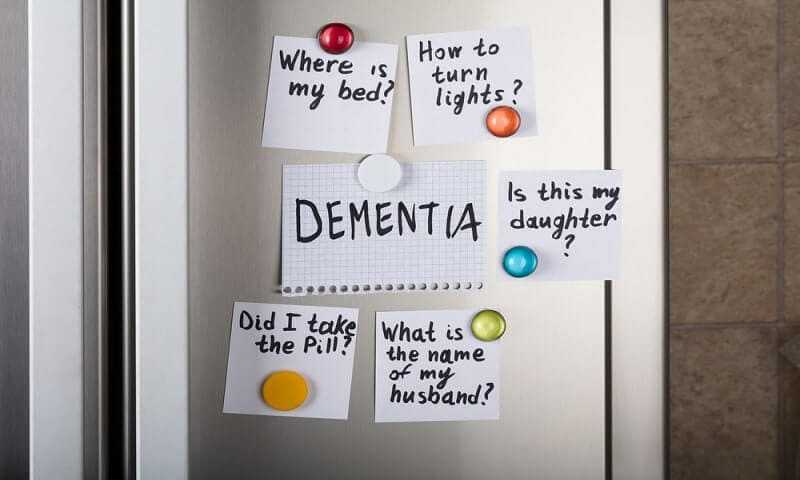

Alzheimer’s disease strikes at family life through the cognitive impairments it creates in the elder. Cognitive losses rob afflicted individuals not only of hard-won skills—but also of the qualities that make them unique and special.

Over time, with steady loss and decline, the elder begins to seem “there” but “not there”— physically present but increasingly psychologically and emotionally absent. Family members mourn the losses. And they find themselves struggling to understand and accept the cognitive and behavior changes—and to maintain their emotional connections with their loved one.

In time, increasingly unpredictable behaviors begin to stand between the elder and his or her family members. The illness—an uninvited, unwelcome intruder—begins to insidiously and relentlessly invade all domains of family life. It takes up residence. It begins to dominate family routines and rituals. And, for many families, the disease becomes a “family illness”—an enveloping, pervasive, inescapable presence that casts a dark shadow over all family activities.

Alzheimer’s disease as disorganizer

Alzheimer’s disease not only invades the family domain—it disorganizes family life. It alters roles and relationships. And it disrupts the family’s stability—the family’s need to maintain an established boundary, a cohesive structure, and an enduring culture. Let’s briefly examine each in relation to the invading and disorganizing nature of Alzheimer’s disease.

Boundary

Alzheimer’s disease raises two family boundary issues. First, the illness places increasing care demands on the family. And these mounting care duties eventually require a collective family response. In order to organize a family response, family members must first determine who’s in and who’s out of the family system —and then determine who’s in and who’s out of the family dialogue.

Answers to these questions will determine (in part at least) who will participate in decision-making activities and who will ultimately enter into family caregiving activities.

Family members must also make ongoing decisions about the ways in which the elder will participate in normal family activities. In the early and (perhaps) middle stages of the disease, the elder’s participation in family routines, celebrations, and rituals can be useful and welcome. In later stages, involvement can unsettle the elder and disrupt family life— and, consequently, rob all family members of needed enjoyments and satisfactions.

Thus, family members must constantly examine boundary issues. Who’s in? Who’s out? To what extent is an individual family member in or out? To what extent should we (and can we) include the elder in family activities?

Answers to these questions help family members clarify (and keep clarifying) the family boundary. Dialogue and discussion around boundary issues will help family members organize a collective response to care challenges—and will help them keep the family organized and focused.

Structure

The invasive and disorganizing nature of Alzheimer’s disease also raises critical structure issues. First, as the elder’s cognitive losses mount, family members find themselves changing their expectations for their loved one—and, consequently, changing the nature of a long-standing and treasured relationship.

Again, difficult questions arise. What can I expect of my afflicted loved one—now and down the line? What does he or she expect of me? How can I best meet my elder’s expectations—while meeting my own obligations and responsibilities?

Second, mounting caregiving duties force changes in expectations among nonafflicted family members. And, since a collective family response is inextricably linked to expectations, more difficult questions arise. Who’s capable of doing what? Who’s willing to do what? What general forms of support can we expect? What specific forms of support can we expect from specific individuals—within specific disease stages?

Certain family members may be willing and able to participate in one way, at one disease stage—and another way (or no way) at another disease stage. Or they may need to adjust their participation as the disease progresses. Thus, changing realities and care demands require an ongoing “expectations” dialogue—an ongoing family conversation that focuses on changing roles and relationships.

Expectations define roles, and they define the tasks that family members are willing and able (and expected) to perform. When family members agree on specific tasks (on who will do what and when), the family structure tends to stay organized. When they’re unable to clearly define expectations, the family structure (its set of roles and relationships) tends to become disorganized.

Thus, family members must constantly consider the family system’s structure. They must continually consider the expectations they hold for themselves (as individuals) and for one another. Are the caregiving tasks clear and appropriate? Are they realistic? Can the caregivers perform them? Are expectations clear? Do they need to be changed and revised? When and how?

Answers to these questions will help the family stay organized. Clear expectations and well-defined roles will help the family maintain stability in the face of a disorganizing and destabilizing illness that permeates family life and challenges family resources.

Culture

Alzheimer’s disease creates dilemmas—problems with no seeming solution. And, in the face of dilemmas, family members often develop differing perceptions and judgements. These differences can lead to tension, disagreement, and conflict—and can seriously disorganize family life.

Families with clear and well-defined values and beliefs can more easily resolve vexing dilemmas. Family members who reflect on their family values—and who make decisions that are congruent with their family culture—will more readily resolve value conflicts. And they will make decisions they can more easily “live with.” (“To what extent should we preserve our elder’s freedom?” “To what extent should we preserve and protect his or her safety?” “What’s constitutes a good balance?”)

Maintaining stability in the face of change

As we noted in this article, all families face change and transformation. And any change (expected and unexpected) disorganizes family life—to some degree. Most families adapt to regular change and maintain a stable family organization. They adapt and move on.

Alzheimer’s disease, however, poses some special challenges. Its dementing and progressive nature strikes at the heart of the family’s ability to stay organized. And the uncertainty surrounding the illness—together with its enveloping nature—holds the potential for demoralizing and deenergizing family life. Let’s look at each of these disorganizing features—one at a time.

Ambiguity

Alzheimer’s disease, insidious and progressive in nature, introduces uncertainty into family life. This ambiguity (difficulty in knowing) is related to some basic questions about the illness. Is it real? Will it get worse? If so, to what extent and at what rate? How should we respond—now and down the line? What does the future hold—for the elder and for the family?

Alzheimer’s families strive for greater certainty. They seek a “roadmap” that will guide them through difficult terrain and help them resolve perplexing dilemmas. This quest is understandable. But, unfortunately, the illness defies “cookbook,” “one-size-fits-all” approaches. Each afflicted individual’s experience with the disease is unique, and each family’s approach is unique—shaped by its own unique temperament, identity, and set of resources.

Moreover, Alzheimer’s disease resembles few other illnesses. Most families possess little or no experience with a dementing illness. And this lack of experience—together with a lack of clear care guidelines—fuels ambiguity (difficulty in knowing) and creates ambivalence (difficulty in deciding).

Ambivalence

The Alzheimer’s journey is marked by ambivalence and by a series of dilemmas— problems with no seeming solution. Family members constantly face unpalatable options. And again and again they find themselves in a state of ambivalence—a state that can express itself in two ways:

1) family members may be unable to determine “right” courses of action (we don’t know) or

2) they may not like any of their options (we see the choices —we just don’t like them).

With no seemingly good alternatives, families find it difficult to mark their successes. With no clear successes, family members can develop a sense of failure and futility—a sense that they’re unable to make any effective decisions. (“What difference will it make?“)

Enveloping and pervasive nature of the illness

Alzheimer’s disease seeps into all sectors of family life. And, over time, it can envelop and permeate family routines, rituals, rules, and relationships. The illness enters into every family interaction and casts a shadow over almost every family activity. The relentless monitoring and care demands can, in time, “engulf” individual caregivers—and can ultimately “take over” family life in ways that undermine individual and family wellbeing.

Demoralizing and deenergizing nature of the illness

Alzheimer’s disease brings sadness and grief into family life. The progressive nature of the illness and the chronic feelings of grief can steal opportunities for hope and joy—and force families to reassess their hopes and expectations. The illness can erode the family vision and undermine the “family dream.” And it can ultimately degrade hope and optimism—and finally demoralize the family system. In the face of a gloomy and forbidding future, the family can get stuck in the “here and now”—moving from one crisis to another without plan or purpose.

The Alzheimer’s challenges, with their constant demands on family strength and resources, require the family to continually and continuously identify and nurture its strengths. But these strengths are considerable—and they are enduring.

They include the ability to maintain a sense of connection and belonging (helped by a clear boundary), the ability to communicate and solve problems (helped by a clear structure and set of expectations), and the ability to maintain a sense of commitment to common goals (helped by clear values and a clear culture).

A family’s response to the Alzheimer’s “invader” is also powerfully shaped by its temperament and identity.

Family resources for meeting the challenges

Temperament

Family temperament consists of the characteristic activity patterns and response styles that families exhibit—as they go about shaping their daily routines and resolving their problems. Family temperament is also shaped by the ways in which various family members interact and “fit together.”

Family temperament is the product of three fundamental properties:

1) the family’s typical energy level,

2) the family’s preferred interactional distance, and

3) the family’s characteristic behavioral range.

The family’s energy level refers to its behavioral activity. We describe some families as high-energy (“hot”) and some as low-energy (“cool”). The family energy level is affected by the intensity of interactions within the family— by the activity level of family members and by the passion that pervades family life.

The family’s preferred interactional distance refers to the degree of involvement between and among family members. Some families are “close”—family members spend time together and know a great deal about one another’s lives. Other families are less close—family members main-rain a looser connection with one another.

The family’s behavioral range refers to the family’s flexibility and creativity. Some families value new experiences and creative approaches. Others prefer consistency, stability, and predictability.

Family identity

Family identity can be viewed as a set of shared values, beliefs, and attitudes that give the family its unique nature— and that distinguish it from other families. This shared belief system—this set of family paradigms, themes, myths, and rules—strongly shapes a family’s view of reality. And it influences the family’s sense of “who we are” and “how we go about our business.”

The family identity rests on certain beliefs about membership (who’s in and who’s out) and on certain long-held values. It rests also on recollections of the family history— on recollections of past shared experiences. And memories of past illnesses and past caregiving experiences—recollections of the ways in which the family met previous challenges—can help the family shape effective approaches to Alzheimer’s care demands.

Family identity plays powerful role in transmitting shared beliefs across generations. The ability of the family to maintain its core identity determines whether the family will take on dynastic qualities—whether it will transmit its traditions and beliefs across generations.

Illness—especially a chronic, progressive, dementing illness like Alzheimer’s disease—can seriously erode family identity. And it can seriously undermine family routines, family rituals, and short-term family problem-solving activities. Each of these three observable behaviors—routines, rituals, and problem-solving activities—provides a window into the nature of underlying family regulatory processes. And each deserves brief mention.

Routines, rituals, and problem-solving activities

Family identity is constantly affirmed through daily routines, family rituals, and shortterm problem-solving activities.

Routines

Routines consist of the background behaviors that give structure and form to daily life— and that impose some order on the pace and patterning of daily activities. Daily activities —meal preparation, housekeeping, shopping— add structure and predictability to daily family life. These daily routines lack flash, and, to the outside observer, they often look repetitive and boring. But they convey a sense of order and comfort—and they strongly reflect a family’s temperament.

Rituals

Rituals consist of special behaviors that possess a strong symbolic content. Family celebrations (Christmas, Passover, weddings, baptisms) call forth highly cherished behaviors. Family traditions (birthdays, vacations, reunions) hold special meaning for family members. And patterned routines (dinnertime, bedtime, leisuretime rituals) are imbued with a sense of specialness.

Rituals affirm and transmit family values and culture, and they help preserve the constancy of the family’s internal environment. Rituals celebrate a common identity and build family morale. They affirm the family’s roots and maintain the family’s connection to the larger community. And they reinforce the loyalty of the participants—while sustaining and nourishing family life.

Short-term problem-solving activities

Short-term problem-solving, the third category of observable regulatory behaviors, is the one most closely linked to family stability. Families strive to balance stability and change needs. And they maintain balance and constancy by responding to the challenges that threaten stability— and by developing and activating the discrete and focused problemsolving behaviors that help them meet specific challenges. Once met, the problem-solving behaviors usually recede into the background.

Chronic illness can disturb all these family regulatory behaviors. Alzheimer’s disease can begin to shape family identity. Family members can begin organizing around the illness, and the illness can become the organizing principle for all kinds of family behavior. The disease can invade family routines and rituals—and can severely challenge family problem-solving abilities and activities. Ultimately, the illness can disrupt and disorganize family temperament and identity—two essential family strengths.

Conclusion

In face of all these challenges, family members might ask, “Is there any good reason to think that we can effectively address this disease—that we can cope with an illness that holds such large potential for permeating, enveloping, deenergizing, and demoralizing family life?”

We think the answer is an emphatic yes. And we think the key lies in the ability of the family to develop an adaptive, learning system that meets the care challenges—while maintaining overall family well-being through all its various phases.

Just as we can describe the afflicted individual’s journey in terms of a series of stages —so too can we describe the family’s experience in terms of a series of phases. Each family will experience the illness in its own unique way. But each family, throughout the course of its journey, will face certain common issues and tasks.