An Attack of Nerves

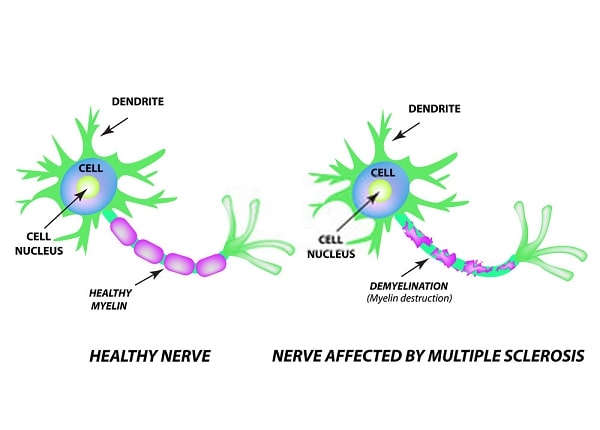

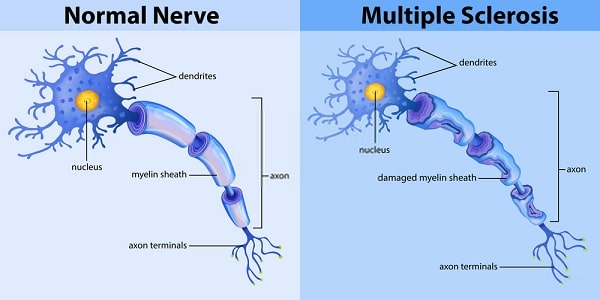

If you can imagine an electrical cord with insulation that’s frayed and worn away in places, causing a short in the wire and then shorting out the electrical system, then you can visualize multiple sclerosis (MS).

In MS, autoantibodies, immune cells, and inflammation damage the “insulation” (called myelin) wrapped around nerve cell fibers in the brain and spinal cord that carry messages to the rest of the body, causing a variety of symptoms, from vision problems to limb weakness. Two-thirds of the 500,000 Americans with MS are women, and the number of new cases among women is rising. The reasons why are unclear; it may be due to better diagnosis or a real increase.

Warning Signs of MS

- Fatigue

- Vision problems—blurred or double vision

- Tingling, numbness, burning sensations in the arms or legs

- Muscle weakness, especially in the legs

- Muscle stiffness or spasticity

- Problems with balance or coordination

- Problems with short-term memory

- Dizziness or vertigo

- Slowed or slurred speech

- Change in bladder or bowel function

More people are now being diagnosed at an earlier stage and started on drug treatments that can slow the progression of the disease. Where once MS could mean disability and confinement to a wheelchair, today most women with the disease lead normal, fully functional lives.

What Causes MS?

Myelin is usually compared to the insulation around electrical wires that helps electrical transmission and protects the wires from being damaged and shorting out. But it’s not really like the single, smooth layer of rubber found on electrical wires. It’s a fatty substance manufactured by specialized cells called oligodendrocytes that coils around nerve fibers (axons), more like multiple layers of electrical tape.

Both myelin and oligodendrocytes find themselves under attack in MS. Autoantibodies reacting to proteins in myelin (including myelin basic protein) and other toxic products of immune cells eat away one or more layers of the myelin sheath and the cells producing it. Since a single oligodendrocyte may spin out myelin for fifty to one hundred axons, an attack on one of these cells can result in problems for multiple axons, notes Anthony J. Reder, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of Chicago. However, because there are so many layers of myelin, it may take a while for the damage to produce symptoms. And myelin may regenerate over a period of months in the beginning (the brain may even reorganize some of its circuits to compensate for minor damage). But the new myelin is not as stable, and eventually spots along the sheath are totally eaten away (demyelination). Inflammation of the sheath at areas of demyelination, which may come in cycles or bursts of activity, is believed to be responsible for MS flares. Immune attacks and inflammation can occur in any area of the central nervous system—the brain, the spinal cord, or the optic nerve—but early on, most of this damage occurs silently.

As myelin is eaten away, messages between nerve cells are increasingly disrupted. When the axon is exposed, it can become damaged or even severed. Accumulated damage to axons can be widespread, eventually leading to irreversible loss of function and permanent disability.

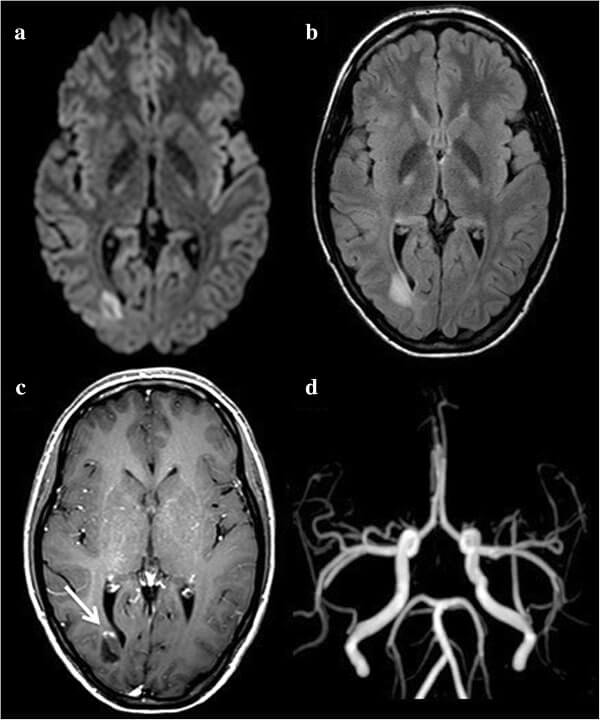

As myelin is stripped away, it’s replaced by scar (sclerotic) tissue, which forms plaques that build up at numerous spots around the central nervous system—hence the name multiple sclerosis. Plaques and inflammation show up as white spots on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is an important diagnostic tool because it reveals plaques even when there are no symptoms. The number of myelin-producing cells are reduced (or they’re absent altogether) within plaques.

For all of this newfound knowledge about the underlying process of MS damage, it’s still unclear what triggers it in the first place. Faulty genes may predispose people to the most common form of MS. Up to 20 percent of MS patients have at least one relative with the disease. While there’s no evidence that MS itself can be inherited, having certain genes may also make people vulnerable to environmental toxins or viruses. Some MS experts believe female hormones may protect nerve cells to some extent.

The agents of destruction in MS are thought to be cell-killing (cytotoxic) T-cells, activated as if to rout a foreign invader, along with hordes of scavenger macrophages attracted by chemicals released by the activated T-cells. In fact, there may be an invader hidden in nerves. Some viruses can infect the body and then remain dormant in nerve trunks. To T-cells, those viruses may look similar to proteins in myelin (molecular mimicry). There are dozens of suspects—including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV, which causes infectious mononucleosis), the respiratory virus Hemophilus influenzae, the mumps and measles viruses, and a herpes virus that causes the childhood illness roseola. We’ve all been exposed to them, and it’s unclear whether they actually trigger the initial MS attack.

Antibodies to these viruses (evidence the body has reacted to an infection) are elevated in people with MS; antibodies have also been found in cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). Evidence of viral infections in the central nervous system and in MS plaques have also been detected. EBV antibodies are increased during MS exacerbations, notes Dr. Reder. “One out of every three upper respiratory viruses triggers an MS attack, probably caused by the activation of the immune system,” he says. Respiratory infections are known to prompt MS relapses (probably through a reaction in “memory cells” programmed by a previous encounter with a virus). But so far there’s no direct evidence that viruses actually cause MS.

One recent study suggests that EBV infection increases the risk of developing MS. Researchers from Harvard analyzed blood samples from 144 women with definite or probable MS and 288 healthy women taking part in the ongoing Nurses’ Health Study. Eighteen of the women developed MS over a ten-year period; 126 had MS or MS symptoms at the start of the study. The researchers found elevations of anti-EBV antibodies in blood collected from the 18 women before they were diagnosed with MS, and antibodies in blood from the other 126 women collected after their diagnosis; levels were all higher than in their age-matched healthy counterparts. A fourfold elevation in antibodies to one fragment of the virus was associated with a fourfold increase in the risk of MS, according to the study reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in December 2001.

Since 90 percent of people have been exposed to EBV at some point, other factors must be involved in MS, such as genetic predisposition, the age at which a woman is infected, or even infection with other microbes, the researchers speculate.

But how would the destructive T-cells get through the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain from toxins? New research indicates that cells in the brain membrane (endothelial cells) somehow become activated and secrete chemicals that attract T-cells, then literally pull them through the cells, crossing the normally impervious blood-brain barrier, says Dr. Reder. These chemicals are called adhesion molecules, because they act like glue. Once inside the brain, myelin-reactive T-cells multiply and likely release chemicals that bring more inflammatory cells into the area to cause damage.

Some scientists believe MS may actually be several different disorders, some of which may be autoimmune and others more like damage from toxins or viruses. Recent research has identified four possible categories of disease based on the appearance of brain lesions; studies are under way to correlate those findings with actual brain tissue samples and MRI images.

Symptoms of MS

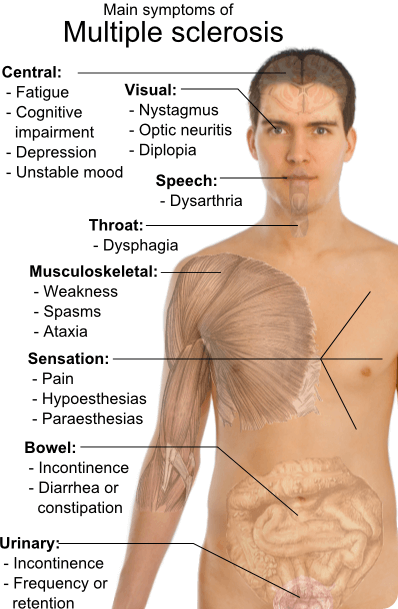

MS can be sneaky—the first symptoms can come and go, and you might not pay much attention to them. A mild tingling in one leg, a little trouble with your eyes. Perhaps some fatigue, joint pain, or trouble remembering things. Sometimes these symptoms last a few days and may include balance problems, slurred speech, and stiffness. Symptoms can resemble other conditions, including Lyme disease, which may delay a diagnosis.

Barbara S. Giesser, MD

The most common symptom is actually fatigue, reported by up to 85 percent of MS patients. “MS fatigue is very distinctive. It’s not a function of physical disability, or of not sleeping, but if you don’t sleep well that can aggravate it. These women sleep eight hours and wake up feeling like they are just drained. It’s generally made worse with heat, and generally gets worse later in the day,” says Barbara S. Giesser, MD, an associate clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles. Unlike other autoimmune diseases, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and fibromyalgia are not usually fellow travelers with MS. “However, I certainly have had patients who were initially diagnosed with fibromyalgia or CFS and turned out to have MS,” she adds.

Depression is actually the second most common symptom of MS, reported by up to 70 percent of patients at some point during the course of their illness. Some women may experience wide mood swings, unprovoked and uncontrollable euphoria followed by extreme depression. In fact, Dr. Reder speculates that sometimes the mood swings attributed to bipolar depression (also called manic depression) could be an early symptom of MS. No brain lesions are found in manic depression, but may be seen in early MS.

Depression in MS may be due to brain lesions or immune dysregulation; depression may also induce abnormalities of immune function that may contribute to MS. A recent study found that treating depression is accompanied by a reduction in interferon-gamma production, one of the inflammatory proteins in MS.

Vision problems are very common, especially optic neuritis. This can take the form of blurred or hazy vision, usually in the central area, or even a complete loss of vision. Problems can come on gradually or suddenly, and resolve quickly. Pain around the eyes may precede loss of vision, sometimes by a few hours, sometimes by a few days. An eye exam may reveal paleness at the back of the eye, indicating optic nerve damage.

Motor symptoms can include a vague feeling of weakness or heaviness in the legs (one leg may tend to drag), as well as a tendency to trip or fall. Five percent of MS patients present with a tremor, while 2 percent may suffer from nerve pain that affects the jaw called trigeminal neuralgia, notes Dr. Reder. Some women may have trouble swallowing or experience facial twitches.

The most common cognitive changes are slowed thinking and memory retrieval, especially visual memory. Corresponding brain changes may even be seen, such as thinning of the corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres of the brain, and a degeneration of nerve fibers.

Some of the sensory changes experienced in MS include tingling, numbness, or feelings similar to small electrical shocks in the limbs or other areas of the body. Some women may experience vertigo or clumsiness. Five percent of women may initially experience bladder problems, a sense of urinary urgency along with more frequent urination, or incontinence. In some women, the bladder may not empty completely and they may have frequent urinary tract infections. Bladder or urinary problems may be the only initial symptoms of MS. Heat can cause a worsening of symptoms, making it even harder for damaged neurons to communicate.

Four types of multiple sclerosis can be diagnosed, based on general patterns of symptoms:

1. Relapsing-remitting: This is the most common type of MS, in which symptoms flare and then go into remission. This respite may be due to bursts of inflammation that subside or to the regeneration of myelin. That inflammation can be seen on MRI using a special contrast agent. Up to 75 percent of people with MS display the relapsing-remitting type.

2. Primary progressive: In this type of MS there are continual attacks on nerves and inflammation, with no remissions, causing increasing disability; about 10 percent of patients have primary progressive MS. (This is actually more common in men.)

3. Secondary progressive: About two-thirds of people with the milder relapsing-remitting MS evolve into a secondary progressive form. This can occur with or without occasional flares, minor remissions, and even long plateaus of stability in the disease. But eventually the disease keeps worsening, with a progressive loss of axons.

4. Progressive relapsing: This is a relatively rare type of MS, occurring in about 5 percent of patients. In this type of MS, there’s a steady worsening of disease from the start, but with distinct flare-ups, that may or may not get better. But there’s continued disease progression in between flare-ups.

Diagnosing MS

In the spring of 2001, an expert panel convened by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society issued new criteria for diagnosing MS, reflecting the latest research. There are now three diagnostic categories: MS, possible MS, and not MS.

The new guidelines keep the threshold of two separate attacks as a requirement for a formal diagnosis of MS. An attack is defined as a neurological disturbance typical of those seen in MS, either reported by the patient or observed by the physician, lasting at least 24 hours. A single episode of muscle weakness would not qualify, but multiple episodes would. The onset of the two attacks must be at least 30 days apart. A clinical evaluation and sometimes three tests—MRI, analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and analysis of Visual Evoked Potentials (VEPs)—are used to confirm a second attack. The clinical guidelines also allow for the diagnosis of people who’ve had only one attack, so they can be started on medication if needed. Evidence of a second attack must be seen on MRI.

There are also people who’ve had no obvious MS attacks, but have had steady progression of disability. For those people, the diagnostic criteria require a positive CSF test, plus multiple lesions in the brain or spinal cord seen on MRI, or an abnormal VEP with fewer brain and spinal cord lesions.

Depending on the symptoms, the neurologist must also exclude other conditions that mimic MS. Blood tests may be needed to rule out other autoimmune diseases or Lyme disease; those tests usually turn out normal in MS patients.

Tests You May Need and What They Mean

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is the most frequently used test for multiple sclerosis, clearly showing the white plaques characteristic of MS. The addition of a contrast agent (gadolinium) can “light up” areas where inflammatory cells have crossed into the brain, causing demyelination.

Plaque that is seen in certain areas of the brain, such as the optic nerve, can be correlated with symptoms. The amount and location of plaques are taken into account in assessing the stage, severity, and progression of the disease. White matter makes up most of the brain, and gets its name from the color of the myelin insulation. Gray matter makes up the cerebral cortex, the multifold outer layer of the brain where most information processing occurs. To be diagnosed with MS with an MRI, separate scans must find at least one gadolinium-enhanced lesion (or a new lesion suggesting inflammation), plus plaques in characteristic areas of the brain or in the spinal cord.

A 2002 study in the New England Journal of Medicine says MRI scans can pick up the earliest signs of the disease in people who have only mild, intermittent symptoms, allowing them to be put on medication as soon as possible. The study followed 71 patients given periodic MRI scans, and among those whose initial test showed plaques in the brain, 88 percent developed MS.

Evoked potentials (EPs) are noninvasive tests that can reveal problems in myelin conduction. During a VEP test, you look at a checkerboard pattern or series of flashing lights while being monitored by a device that measures the conduction of visual images from the eyes to the brain. A delay or prolongation of conduction signals (or weaker conduction) is seen when there’s demyelination. EPs are especially useful in confirming a diagnosis of MS, because they can often detect lesions not seen on MRI.

Lumbar puncture or spinal tap tests a sample of cerebrospinal fluid for antibodies and proteins that result from the breakdown of myelin. Under local anesthesia, a hollow needle is inserted into the spine to withdraw a small sample of the fluid bathing the spinal cord and brain. The fluid is then examined for the presence of abnormal levels of immunoglobulins (which are occasionally autoantibodies), fragments of myelin basic protein produced by inflammation, and for immune cells. This helps to distinguish MS from other nervous system diseases.

Looking for traces of myelin basic protein in urine, along with MRI scans, may help identify women whose disease is transforming from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS (a sign of more damage to come). A study of 662 MS patients reported in 2001 by researchers at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and other centers found that such a test could be helpful in predicting the course of the disease.

The severity of MS is scored using a numerical scale. The Extended Disability Status Score (EDSS) measures vision, sensation, coordination, strength, and walking ability. For example, a score of 0 indicates a normal neurological exam. A score of 1.0 to 1.5 indicates an abnormal neurological exam, but no disability. A score of 2.0 to 2.5 shows mild disability, while a score of 3.0 to 3.5 shows mild to moderate disability. By the time a patient has a score of 6.0, they need a cane to help them walk.

Some clinical signs of MS can provide helpful clues along with the EDSS. For example, women who present with optic neuritis show paleness in the back of the eye after symptoms resolve; the paleness indicates a lesion on the optic nerve that caused demyelination, says Dr. Reder. Some women may show an impaired response to a pinprick, heat, or light touch in areas that correlate to areas of nerve damage. Clumsiness and an impaired ability to sense vibrations can be signs of demyelination that can sometimes be correlated with an MRI (however, often MRIs do not correlate with symptoms).

MS Clusters

The problems that often cluster with MS are not all autoimmune. But the fatigue and depression of an underactive thyroid may not be apparent if you’re having similar symptoms from your MS. So it’s important to be aware of anything that occurs in addition to MS symptoms.

- Hypothyroidism

- Fibromyalgia and arthritis pain

- Epilepsy (may occur in 5 percent of patients)

- Ulcerative colitis

Interstitial cystitis

The Female Factor

Over the years, there have been hints that female hormones may play a role in MS. For one thing, there are fewer MS relapses during pregnancy, when estrogen levels are increased. This may be partly due to pregnancy-associated elevations of a weaker form of estrogen called estriol, normally produced in small amounts in fatty tissues. Lower levels of estrogen that are usually present in the body may not be enough to protect against MS. Animal studies also show that testosterone may be protective, and this may be one reason men get MS less frequently (and later in life).

“There are all sorts of immunosuppressant substances produced during pregnancy. When you look at women with relapsing-remitting MS who become pregnant, the relapse rate during the nine months of pregnancy goes dramatically down, especially in the third trimester, compared to prepregnancy levels,” says Dr. Giesser. “There’s an increase in the relapse rate immediately postpartum, in the three to six months after delivery, and then the relapse rate returns to prepregnancy levels.” She cites one study that included MRIs of pregnant women with MS. “Two women who were in a study protocol happened to get pregnant, and they elected to stay in the study. They were given MRIs during pregnancy, and lesion activity went down during pregnancy and rebounded after they delivered. But we just don’t know why.”

Studies that have followed women with MS for long periods of time after pregnancy have found that they do not have increased long-term disability compared to women who have not been pregnant. “And there are a couple of studies to suggest that pregnancy may even have kind of a protective effect, that people who became pregnant may have a little longer time before increased disability, or the onset of things may be delayed,” she adds. Again, it’s not clear if that’s due to hormones.

“A lot of the sex differences in MS may be due to the protective effects of testosterone, and pregnancy-associated levels of estriol. But that’s probably not the whole story. Sex chromosomes may also have a role in making the disease better or worse,” says Rhonda Voskuhl, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Voskuhl is studying the effects of estriol on MS.

Relapsing-remitting MS is largely inflammatory, and estrogen may act as an antiinflammatory agent, observes Dr. Voskuhl. When female mice, engineered to develop an MS-like disease, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), are given estrogen, they produce higher levels of an anti-inflammatory cytokine. And the effects of estrogen during pregnancy also dampen inflammation in the immune system, she notes.

Dr. Voskuhl initially studied the effects of estriol in mice with EAE and found that they had fewer exacerbations, less disability, and improved health compared to mice not treated with the hormone. Based on these results, she conducted a small pilot study of estriol among twelve women, six of whom had relapsing-remitting MS and the other six with secondary progressive disease. “We saw a beneficial effect on the immune system, we saw lesser reactions to skin testing. On MRI we saw about a 50 percent reduction in gadolinium-enhanced lesion volume in relapsing-remitting patients, and the number of lesions was reduced by around 20 percent. The secondary progressive patients did not show any benefit.” During the treatment period, there seemed to be some stabilization of lesions caused by T-cells, as well. “What we are doing now is a larger study among relapsing-remitting patients to see if we can have statistically significant results.”

Dr. Voskuhl also hopes to see clinical trials of estriol in combination with the so-called ABC drugs (Avonex, Betaseron, and Copaxone) to see whether it will enhance their effects. Estriol, made from soybeans, is widely used in Europe to treat hot flashes, but is not yet approved for use in the United States.

Another sex difference may be due to inflammatory cytokines. During pregnancy, levels of interferon gamma (a damaging inflammatory cytokine associated with MS) are lower. A small study at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation revealed that when T-cells from women with MS were stimulated with a myelin protein, they produced higher levels of interferon gamma compared to men. At the same time, women with MS produced none of a regulatory cytokine that may dampen the disease process. It’s not clear what role, if any, sex hormones may play in this response.

However, the inflammatory immune response does switch to a regulatory response during pregnancy (so the body doesn’t reject the fetus), and MS typically improves during pregnancy, when estrogen and estriol levels are high. Researchers at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation say a possible new direction in MS therapy would be stimulating that regulatory response.

Another recent study found that a combination of estrogen and a T-cell receptor vaccine completely prevented EAE in female mice, and those mice getting either estrogen or the vaccine developed fewer symptoms than mice getting no treatment. The researchers, at the Neuroimmunology Research Program at the Portland Veterans Administration Medical Center in Oregon, developed a vaccine that blocked certain T-cell receptors, preventing them from interacting with myelin. The vaccine also increased the number of regulatory immune cells that keep autoreactive T-cells in check, the researchers reported in 2001. They plan to design a pilot study for humans.

Another new avenue of therapy may come from studying estrogen’s effects on specific brain cells. One of the ways estrogen suppresses EAE in mice is by changing the action of T-cells and the activity of brain cells called microglia, which can produce toxic molecules that attack myelin-producing cells. Studies are under way to see whether female hormones can suppress these attacks. Dr. Voskuhl is also looking into adding progesterone to estriol, which she believes may enhance its effects.

But all of this doesn’t mean estrogen can be prescribed as a treatment for MS yet. “We’ve only done a pilot study. The results are interesting, but must be confirmed in a placebocontrolled trial. Also, the doses we used are pregnancy doses, which are high levels of estriol. So I don’t know what effect the estrogens and doses found in birth control pills or hormone replacement will have on symptoms,” remarks Dr. Voskuhl. “Conjugated equine estrogens are made from the urine of pregnant mares, so they contain estriol. So Premarin may help—or it may do nothing. We simply don’t know.”

However, Dr. Voskuhl and Dr. Giesser believe estrogen—either in birth control pills or in hormone replacement therapy—can be safely used by women with MS, as long as they’re being followed by a gynecologist.

Treating Multiple Sclerosis

Under the new diagnostic criteria, a woman who experiences a single MS attack can be started on medications that have been shown to slow the progression of the disease—in many cases preventing permanent disability.

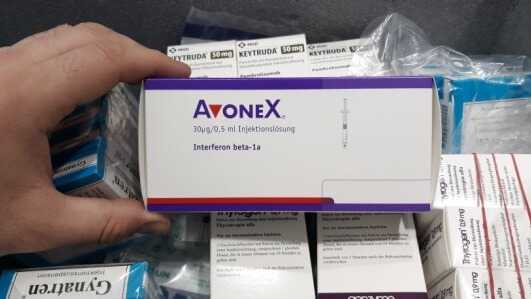

This change in treatment was largely brought about by a major study reported in the September 28, 2000, New England Journal of Medicine. The trial, known as the CHAMPS study, was conducted among 838 men and women at 50 clinical centers in the U.S. and Canada judged to have a high probability of developing MS based on symptoms and findings on MRI. The group was randomly assigned to weekly injections of interferon beta-1a (Avonex) or placebo. The trial was supposed to last three years, but after a planned pause to survey interim results, the trial was stopped early because the effects were so positive. The upshot: weekly injections of Avonex were found to delay the onset of clinically definite MS by 44 percent and produced a lower rate of brain lesions. New research also found that Avonex slows the brain atrophy associated with MS.

Since CHAMPS, many women can begin treatment after the earliest symptoms of MS appear. The medical advisory board of the MS Society recommends that treatment be started as soon as possible (except in pregnant women) with one of the new MS drugs: Avonex, interferon beta-1b (Betaseron), or copolymer-1 (Copaxone), known as the “ABC drugs.” A new interferon drug, interferon beta-1a (Rebif), is now available.

Interferon beta-1a (Avonex) works like natural human interferon to dampen immune system activity. Avonex was approved by the FDA in 1996 to reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations in people with relapsing-remitting MS, but is now being used to treat people who have experienced a single MS attack, to slow down the disease. The drug is given by self-administered injection once a week into the large muscles of the thigh (or hip or upper arm muscle). Avonex reduces relapses by about 18 percent, slows MS progression, and studies show it may help cognitive impairment in relapsing MS.

Side effects include flulike symptoms (chills, fever, aches) after the injection, which lessen as time goes on. In rare cases, Avonex can cause mild anemia and elevated liver enzymes (suggestive of liver inflammation), so patients must be monitored.

Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron) was the first of the ABC drugs, approved in 1993. It also works like natural human interferon to inhibit immune system activity and reduces MS relapses by about 30 percent. It’s injected under the skin every other day.

Betaseron also causes flulike symptoms after an injection (which also lessen after a while). Women can also experience reactions at the site of the injection (which can be serious and require medical attention in about 5 percent of cases). It can also cause elevated liver enzymes and low white blood cell counts, increasing the risk of infection.

A study comparing Betaseron to Avonex found it was more effective in reducing relapses, but further studies are needed. Avonex and Betaseron both can cause menstrual irregularities in about 15 to 25 percent of women.

Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) is a synthetic protein that looks like myelin to the immune system. Its neuroprotective effects haven’t been proven in MS, but it seems to block attacks on myelin by T-cells, apparently acting as a decoy for myelin. Copaxone is approved for relapsing-remitting MS. A long-term clinical trial among more than 250 patients with relapsing-remitting MS found that most of those who stayed on Copaxone had an improvement in their neurological status or remained unchanged after eight years. Interim results of the twelve-year trial, led by the Maryland Center for MS at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, were reported at the 2002 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Another study found that Copaxone stopped new brain lesions caused by MS flares and reduced the amount of damaged brain tissue over time, with the protective effects appearing three to four months after treatment began.

Copaxone is available in prefilled syringes and given by injection once a day. It can cause reactions at the injection site. In rare cases, there may be anxiety, chest tightness, shortness of breath, and flushing right after an injection, but there do not seem to be any long-term consequences.

“I like to think that these drugs give the brain a ‘breather,’ allowing more of the normal remyelination to occur,” says Dr. Reder. The ABC drugs all cost around $10,000 a year, but are available at a reduced rate through the manufacturers.

Interferon beta-1a (Rebif) was approved by the FDA in March 2002 for relapsingremitting MS. It also works like natural human interferon. Studies showed Rebif reduced the frequency of MS exacerbations, reduced disease activity seen on MRI, and slowed the progression of disability. A 2001 study comparing Rebif to Avonex showed it produced a 32 percent reduction in relapses compared to Avonex. Another trial showed Rebif could delay MS development as the ABC drugs did in the CHAMPS study.

Rebif is prescribed in prefilled syringes and given by self-injection three days a week at the same time of day, with each injection forty-eight hours apart. There can be reactions at the injection site (soreness, redness, pain, bruising), so you’re advised to pick a different spot each time to lessen the chance of an infection or other problem. Side effects include flulike symptoms (fever, chills, muscle aches, and tiredness), depression and anxiety, liver problems, a drop in red and white blood cell counts, changes in thyroid function, and allergic reactions. Periodic blood testing is needed to monitor liver or blood changes. Like the ABC drugs, Rebif cannot be used during pregnancy.

Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) is an anticancer drug that suppresses T-cell, B-cell, and macrophage activity, and seems to lessen attacks on myelin. It is usually given intravenously every three months for up to two years (or up to a specific cumulative lifetime dose). A 2002 study from France, where it has been used for more than a decade, found that an initial “induction” course of more intense mitoxantrone therapy for six months significantly reduced relapse rates, and kept 43 percent of patients relapse free for a five-year period. Recent studies also suggest that combining Novantrone with Betaseron is safe and may reduce disease progression without significant toxicity in people with aggressive relapsing-remitting disease, or secondary progressive disease, whose MS wasn’t controlled by Betaseron.

Novantrone can affect the heart, raising the risk of congestive heart failure. So you must have normal heart function to take the drug, and tests of cardiac function are necessary before and during treatment.

Targeting Common Symptoms

Other treatments for MS target symptoms, such as pain, tremor, bladder or bowel dysfunction, and fatigue.

“Up to 85 percent of MS patients have fatigue, and it may be the single most disabling symptom,” remarks Dr. Giesser. An antiviral medication called amantadine is widely used to treat MS-related fatigue. Some patients benefit from a stimulant used for hyperactivity, methylphenidate hydrochloride (Ritalin). A newer stimulant, modafinil (Provigil) has been very effective in clinical trials against MS-related fatigue. Antidepressants such as fluoxetine (Prozac) may also help fatigue.

Physical, occupational, and/or cognitive therapy may sometimes be recommended. A landmark 1996 study at the University of Utah found that aerobic exercise produced many physical and emotional benefits for MS patients, including improved bowel and bladder control and reduced fatigue.

Most MS patients are sensitive to increases in body heat, so exercising in an airconditioned room is highly recommended. Dehydration can exacerbate fatigue, but many women with MS don’t drink enough water because of bladder incontinence. But getting enough water during exercise is extremely important.

Anti-seizure medications like carbamazepine (Tegretol) and gabapentin (Neurontin) help nerve pain. Other drugs used for MS-related pain include the tricyclic antidepressants amitriptyline (Elavil) and imipramine (Tofranil), which interfere with pain signals from nerves. Antispasmodic drugs, such as baclofen (Lioresal) or tizanidine (Zanaflex), can help leg or back spasms. Prednisone may be given for optic neuritis.

MS patients have specific bladder problems. “In MS, the bladder often doesn’t store urine properly. So instead of holding a normal volume of urine, around two or three cups, before you have the urge to go or before you empty reflexively, a patient’s bladder may hold only a cup or so. The result is urgency, a spastic, nervous bladder that wants to go all the time,” says Dr. Giesser. “Or, MS patients may have a bladder that doesn’t empty itself completely, so when you void there’s still urine in the bladder, which leads to urinary tract infections, urine reflux (it can theoretically back up into the kidneys), and kidney disease. And there are women who have a ‘mixed’ bladder, a bladder that wants to empty all the time, but doesn’t empty well.”

For a purely spastic bladder that doesn’t store urine well, patients are prescribed anticholinergic agents, drugs that relax the bladder and allow it to hold more urine. In some cases, women are taught how to use urinary catheters. “For ‘mixed’ bladders we may use medication along with self-catheterization. It’s very individual.” A new procedure, sacral nerve stimulation, a kind of “pacemaker” that helps eliminate abnormal nerve signals to the bladder, may work for some women with MS, she adds.

Another common problem is constipation. “Women who are less mobile are more prone to constipation. Some of the drugs we give cause constipation. A lot of women with bladder problems self-treat by restricting liquids and become dehydrated, which contributes to constipation. And MS probably has some effect on gut motility, as well,” says Dr. Giesser. In general, women with MS are advised to increase fiber intake, take bulking agents, keep well hydrated, and eliminate on a schedule to help keep regular.

Studies conducted by the NMSS show that two out of three people with MS will remain ambulatory twenty years after diagnosis, and those numbers should improve as more people are treated earlier for the disease. Again, just because you’re not experiencing a relapse doesn’t mean there’s no disease progression. So medication is needed.

What’s Next?

New drugs in the pipeline include natalizumab (Antegren), now in Phase III clinical trials. The drug, a new class of therapeutics called alpha 4 integrin inhibitors, is designed to prevent the migration of inflammatory cells from the blood to other sites in the body. (In MS, it would block adhesion molecules that attach T-cells to cells lining the blood vessels in the brain and draw them across the blood-brain barrier.) Preliminary results reported in 2001 showed that Antegren slowed the relapse rate by 50 percent and lesions seen on MRI by 80 percent, notes Dr. Reder. It’s also being tested in Crohn’s disease.

Avonex and Betaseron are being tested against secondary progressive MS, and Copaxone and Avonex are being tested in primary progressive MS.

Scientists are also investigating the possibility of stimulating immature (or progenitor) myelin-making cells or transplanting those cells into patients with MS. Other experimental treatments being tested in animals include exposing autoreactive T-cells to large amounts of myelin basic protein in an effort to induce programmed cell death. Monoclonal antibodies and immunoglobulins are also being tested in animal experiments to regrow myelin.

Ritonavir, a drug used to treat human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), has shown potential benefits in preliminary animal studies. Ritonavir is a protease inhibitor, which affects an enzyme (called a proteasome enzyme) thought to play a role in the activation of lymphocytes that attack the myelin sheath in MS. Daily doses of ritonavir prevented clinical symptoms in the animal model of MS in such a way that researchers feel it may have a protective effect when given early in the disease. MS also seems to respond to other antiviral therapies.

Drugs used to treat Alzheimer’s disease are also being tested to see whether they can slow cognitive decline in MS. Preliminary indications are that donepezil (Aricept), slightly improved cognitive function in the small group of patients who have tried it, Dr. Reder reports, but definitive data will have to come from clinical trials. Newer drugs such as galantamine (Reminyl) may be even more effective.

A small, preliminary study reported at the American Academy of Neurology annual meeting in 2002, suggested stem cell transplants might be effective in severe MS.

I hope you have enjoyed this article. If you have further questions please comment.

Wishing you joy and healing.