Arthritis in Children

Children get arthritis too. In fact, over 30,000 children in the United States have an important kind of arthritis called juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA). This name, however, is misleading, since it suggests that these children have a disease similar to rheumatoid arthritis in adults. For the most part these children have a quite different set of problems and require quite different treatment. The outlook for their complete recovery is much better than that of persons with adult rheumatoid arthritis.

Children, of course, lead very active lives and continually put stresses on their joints, muscles, and back. They fall down, sprain their ankles, and experience a variety of temporary aches and pains that are not really arthritis. Occasionally a child will be born with an abnormality in a knee, hip, or elsewhere. Again, this is not reallv arthritis. Very rarely, a child will have a joint infected with bacteria (most commonly the Staphylococcus), which causes a severe infectious arthritis like that discussed later. An adolescent will sometimes develop arthritis due to infection with gonococcal bacteria. These problems are true arthritis, but they are acute forms. They develop rapidly and last less than six weeks. In this article we are concerned with arthritis of longer duration in children.

Three forms of juvenile arthritis are now generally recognized. The first, monoarticular arthritis, occurs in only one joint or, at most, in two, three, or four joints. The second, systemic arthritis, is more impressive for its high fever and its skin rash than for the arthritis itself. The third, polyarticular arthritis, invokes many joints and resembles the rheumatoid arthritis seen in adults.

Beyond these major subtypes, there are other kinds of chronic arthritis in children. Acute rheumatic fever is a completely different disease that must not be confused with other forms of childhood arthritis. And some kinds of attachment arthritis described in this article, such as ankylosing spondylitis, can occur in adolescents.

Features of JRA

The following paragraphs describe the features of the three types of juvenile arthritis, and acute rheumatic fever.

Monoarticular juvenile arthritis simply means juvenile arthritis that involves only one joint. Most frequently this joint is a knee. Pauciarticular and oligoarticular are similar words that mean “few joints” and allow for the fact that this type of arthritis may involve one, two, three, or even four joints. Usually the joints involved are large ones. Most children with pauciarticular arthritis feel generally well except for their swollen, sore, affected joints. In a few instances there may be involvement of the eye.

Many doctors will ask an ophthalmologist to perform periodically a slit lamp examination of the eye to detect any eye problems. In this procedure, a thin beam of light is projected obliquely onto the eye through a narrow slit to permit examination of the eye by a magnifying lens.

The systemic form of juvenile arthritis is far more dramatic. This form has been called Still’s disease. A child may suddenly develop a very high fever, as high as 106°F (41°C), and may be very ill with fatigue, muscle aching, and perhaps a fine, red skin rash. The liver, spleen, and lymph nodes may be enlarged, and the disease may involve other organs as well. The attack may last days or weeks and disappear as quickly and mysteriously as it came. A few months or years later it may recur again and again and again. With the initial attack there may be just a little arthritis, quite a bit of arthritis, or no arthritis at all. Eventually arthritis will accompany every attack, but this may not occur for several years.

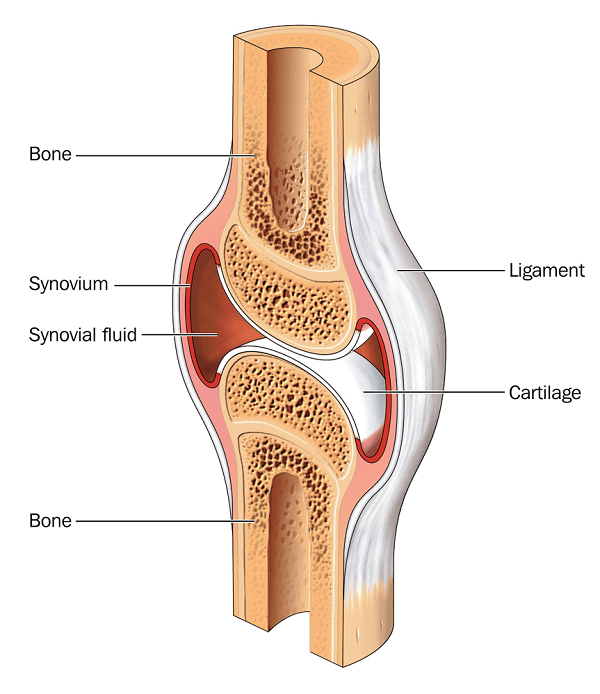

Polyarticular juvenile arthritis affects many joints and usually comes on slowly in children approaching adolescence. The arthritis is usually experienced equally on both sides of the body and frequently affects the wrists and knuckles as well as the knees and other joints. This form is characterized by intense inflammation of the joint membrane (synovitis), and closely resembles the rheumatoid arthritis seen in adults.

Acute rheumatic fever follows a streptococcal infection, usually a “strep throat.” It is a much less frequent illness now than it was a few years ago. The possibility of acute rheumatic fever is the major reason that throat cultures are taken and that penicillin is sometimes given to treat sore throats, since rheumatic fever can be prevented by such treatment. Acute rheumatic fever is an allergic (immunologic) reaction of the body against a strep bacteria infection that occurred several weeks earlier. Antibodies attack the joints, and sometimes the heart valves and other parts of the body.

The arthritis of rheumatic fever is termed migratory. It will, for example, appear in one joint, such as the knee, then migrate to a shoulder, then to a wrist, and then to the other knee. Affected children may have a heart murmur, a fever, or an unusual red skin rash with sharp, irregular borders.

Tests

Laboratory tests for juvenile arthritis are not very helpful. By and large, all of the usual tests for arthritis are negative. Even in children with the polyarticular arthritis most closely resembling adult rheumatoid arthritis, only a minority have a positive rheumatoid-factor test. The sedimentation rate is often elevated, but this indicates the severity of the inflammation and not the accuracy of the diagnosis. With acute rheumatic fever, a blood test can confirm that a streptococcal infection has occurred recently.

Similarly, X-rays are usually not very helpful. This is a fortunate thing, since we do not like to X-ray children unnecessarily. Destruction of the joints sufficient to cause X-ray changes to the bone is uncommon in children. Watching the course of the disease with time often provides the most important diagnostic clues. Does the arthritis stay in the original joints? Are there associated skin rashes or fever? Does the arthritis come in recurring attacks? Does it tend to involve both sides of the body equally? Such questions, repeated over time, require patience on the part of parent, child, and physician. The patience is usually rewarded by a good outcome for the child.

Prognosis

Many of us have the idea that arthritis, once encountered, is present for life. This is not true. When a child develops arthritis, the concern of parents, child, and even the child’s school is naturally intense. Fortunately, in children the disease usually disappears entirely with time. Most children with juvenile arthritis will grow into normal adults without any leftover bone or joint problems. This does not mean that parent or child can relax. Hard work is required to prevent development of permanent stiffness, particularly when a period of active arthritis coincides with one of rapid growth. The long-term outlook, however, is good.

This is particularly true of the first two categories of juvenile arthritis. At least two-thirds of children with monoarticular or pauciarticular disease will have no problems with arthritis as adults. Even with the dramatic systemic form (Still’s disease) a similar twothirds of children will have no problems as adults. The outlook is not quite as favorable for children with polyarticular arthritis; about half of these children will continue to require treatment for arthritis in adult life.

Acute rheumatic fever does not cause joint destruction, and arthritis continuing into adult life is unusual.

Treatment

Medications

Drug treatment of arthritis in children centers around the use of NSAIDs. Aspirin, an anti-inflammatory, in appropriate doses, will satisfactorily control the arthritis in the great majority of patients. Some of the new anti-inflammatory agents are also useful and may be safer, but not all are yet approved for use in children. Tylenol is safe and is frequently used; aspirin should be avoided in children with fever.

On the other hand, the bad effects of the corticosteroids on childhood growth are well understood; these agents stop bone growth and can lead to failure to reach adult height. Other side effects of steroids also occur; thus, these drugs must be used with extreme caution in growing children. Their most justifiable use is in short courses of treatment for the dramatic but brief episodes of illness with Still’s disease, or occasionally for severe eye problems.

The careful physician relies on aspirin or other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as the major medication for pauciarticular disease. Parents, child, and physician must always take the long view. An exception is that with very high fever, chicken pox, or influenza, most doctors now avoid or discontinue aspirin because of the possibility of triggering a severe liver and neurologic condition known as Reye syndrome.

Methotrexate is now being used more frequently in children with polyarticular disease, as are the other DMARDs.

Exercise

Physical therapy and exercise programs, particularly swimming, are very helpful in maintaining muscle tone and mobility in the child with arthritis. Sometimes special arrangements with the child’s school are required so that the child doesn’t fall behind during the time the arthritis is expected to remain active. Since the overall outlook is good a reasonable plan of management includes attention to keeping the child up with his or her peers, so that when the arthritis subsides a normal school and social pattern can be resumed. For many patients, body contact sports and activities (such as basketball) that require a lot of jumping should be discouraged, but only while the disease is active.

Surgery

Surgery is seldom required, and indications for surgery are similar to those in adults. It is needed only infrequently because the destructive aspects of the arthritis are less severe in children. Surgical removal of the synovium (joint membrane) of the knee is sometimes required, but this is performed less frequently now than a few years ago. “Soft tissue release” procedures to increase motion (capsulotomy) are fairly frequently performed.

Rather rarely, removal of joint fluid through a needle provides some relief. Sometimes injection of a corticosteroid preparation into a knee joint or other joint is helpful. Since too many treatments of this kind can accelerate bone destruction, they must be used with caution.