Treating Pain with Narcotics

Imagine that you have found the perfect, life-enhancing gift to give a friend, but it must be wrapped in three sheets of paper. Before your friend can reach the gift, he must examine each paper and read its message. The first sheet of wrapping tells him that refusing gifts is a sign of strong and admirable character and that he must refuse gifts if he wants to be a “real man.” The second says that the contents of your gift will cause him to become a drug addict, which could lead to various forms of degradation and at best a period of painful, horrific withdrawal. The third wrapping, if he has gotten this far without running away, informs him that the gift is so dangerous that it must be regulated by the government. In fact, a government representative may be preparing to investigate him even as he reads.

This story pretty much represents the position of many patients in significant chronic pain. Helping someone find and accept the proper narcotic drugs for debilitating chronic pain is mixed up with ideas of personal weakness, images of addiction and its associated lifestyle, and government regulation.

How Narcotics Work

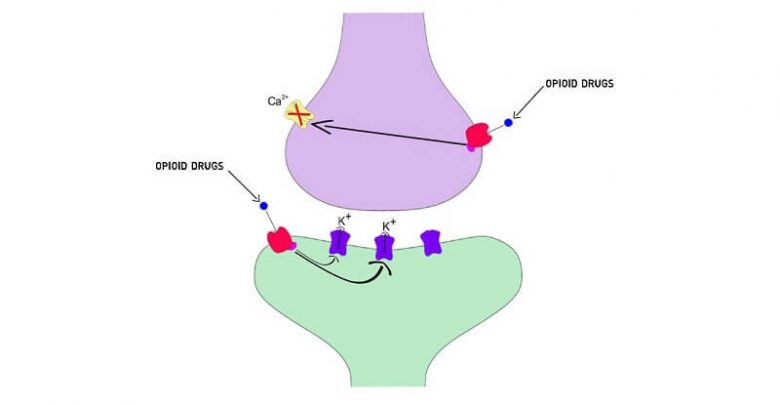

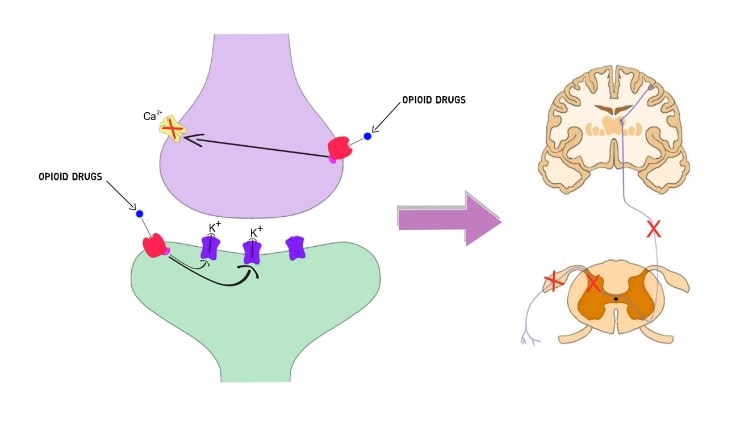

Narcotics work and have side effects for the same reason. In the early 1970s, two medical scientists at Johns Hopkins, Drs. Solomon Snyder and Candice Pert, discovered receptors for narcotics or opioids in the brains of mice. A bit later, another group of scientists discovered certain protein molecules called endorphins, which fit like a key into a lock, the lock being the receptors. The relationship between these endorphins and our own pain control was thus demonstrated. However, opioid receptors were found in other organs as well, and it was surmised that these receptors play a role in all sorts of bodily functions, including pain, pleasure, and the degree of dependence on and tolerance to opiates.

Narcotics like morphine are not perfect three-dimensional molecular matches for our own opioids. They are keys, which fit the lock imperfectly. Yes, they fit well enough to provide great pain relief, but they also fit into other locks or receptors that have nothing to do with pain control, and that is the basis for their side effects. It is the binding to receptors in the base of the brain, which influence the gastrointestinal tract, that cause some people to have nausea, at least transiently, and almost all patients to have constipation when taking narcotics. Similarly, receptors to which man-made narcotics bind may depress respiration, another potential side effect. Some narcotics may alter your mood by binding to still other receptors.

Not all narcotics bind to receptors in the same way in each person. Some patients may tolerate morphine, Dilaudid (hydromorphinone), and fentanyl (used in Duragesic skin patches), three different narcotics, without a significant problem. In other cases, a patient may tolerate morphine but vomit when taking Dilaudid or fentanyl. Incidentally, the latter drug appears to cause 30 percent less nausea and constipation than other narcotics —it bonds to certain receptors less than its narcotic colleagues.

A crucial issue with narcotic drugs is tolerance. Tolerance means a drug’s effect decreases over time, presumably because of some physical change—a reduction in the number of receptors for a drug or a change in the configuration of the receptor, the lock for the drug’s molecular key.

The good news is that most people become tolerant of many side effects of narcotic drugs within one or two weeks (except constipation, which usually has to be treated on a long-term basis) while still obtaining good pain relief. The reason for this differential tolerance is not clear. Perhaps the interaction of many narcotics with the receptors causing side effects is different from the interaction with the receptors causing pain relief.

The bad news is that some patients also become tolerant to the pain-relieving properties of a narcotic. If this occurs, changing to another narcotic that binds to our pain-relieving narcotic receptors differently may help better control the pain. This strategy may fool or outwit the mechanism of tolerance.

Man-made narcotics are more potent than our own natural opioids, the endorphins, but both work along the same lines. If you were taking morphine when you touched a hot stove, your reaction to the heat would be slower than if you didn’t take the pain reliever. It may take more heat to make you jump and you might jump away more slowly. You still would jump, however, and learn not to touch the hot stove in the future. Once you have been treated with morphine, the pain-transmitting cells in the spinal cord are forced to slow down. They are inhibited from rapidly firing in response to the incoming barrage of pain signals, which are carried into the spinal cord along the nerve coming from your burned finger. The morphine acts like a brake, modulating or inhibiting an important segment of the pain-transmission system.

Why Most People Won’t Become Addicted to Narcotic Pain Treatment

Remember that first cigarette behind the garage? Boy, did it make you green. Your body wasn’t used to it. If you were foolish enough to keep smoking, you got used to the effect of nicotine—tolerant to it. You wouldn’t feel green, and would want to smoke more cigarettes, and even feel terrible if you didn’t have any. You became dependent on nicotine. Worse yet, you might have grown to crave them, purely because you liked to smoke or liked the way smoking made you feel. That craving is addiction, often confused with tolerance and dependence.

Tolerance means that the body adapts to an opiate so that both therapeutic and side effects are diminished. Fortunately, tolerance to the side effects of opiates develops relatively quickly but tolerance to the pain-relieving effects of these drugs develops slowly, for unclear reasons. Most chronic pain, once controlled, may be treated with a stable dose that never has to be increased. In practical terms, someone in chronic pain may take the equivalent of six to eight Percosets daily for years, with good results and few side effects. He gets used to the drug.

If a person not used to that amount of narcotic took it, he would be sleepy and act as if overdosed.

Dependence is physical adaptation to the presence of a drug, narcotic or non-narcotic. Has someone in your office ever decided to go off caffeine for a while? Why, a person can become a bear—jittery and headachy. You’ve seen them. If coffee drinkers go without their drug, they will have some withdrawal symptoms—just like withdrawal from narcotics.

Dependence and tolerance are normal physiological adaptations to the exposure of the central nervous system and the rest of the body to a chemical on a regular basis. Now, the real bugaboo with narcotics is addiction. What does it make you think of? Dazed people lying around an opium den or in a filthy crack house? Drugs are not paving the road to hell when they are prescribed for the medical control of pain. Addiction, by any definition, is compulsive, inappropriate use of a drug for a psychological reason —to get high. Use for pain control is not addiction.

The most commonly abused drugs in the United States that result in emergency-room visits for overdose are cocaine, heroin, and Valium-like drugs, in that order. Notice the conspicuous absence of any prescription narcotics from the top of the list.

Pseudo-addiction is drug-seeking behavior by patients whose pain is not adequately controlled. The nurse complains, “That kid down in room 404 who keeps asking for her pain medication must be an addict.” No, she was just in a bad motorcycle accident and broke a leg, which needed open surgery to repair, and skinned half the upper layer of flesh off her back. Her doctor prescribed oral narcotics every six hours as needed, in spite of the fact that the medication only lasts three to four hours. He also prescribed about half the amount of narcotic she needs to take the edge off, much less make her truly comfortable. That kid in 404 may be obnoxious outside the hospital for other reasons, but now she is whining because she is in excruciating pain and cannot imagine how she’ll ever get comfortable, much less go to sleep. Most patients in pain asking for more narcotics are undermedicated. Don’t ever forget that. Her demand for more drugs is pseudo-addiction. Real addiction is when a person demands a drug whether or not she is in pain.

In a study of national databases, the use and abuse of five narcotics, including fentanyl, Dilaudid, Demerol (meperidine), morphine, and oxycodone, the narcotic in Percoset, were studied from 1990 to 1996. Use of these drugs increased severalfold while abuse decreased. The trend clearly demonstrates increasing medical use of narcotics for pain control and no associated increase in narcotic abuse. The trend obviously should continue.

Why Your Physician Won’t Prescribe Narcotics

Vastly exaggerated fear of addiction is one major reason physicians underprescribe narcotics. An even more important impediment to the medical use of narcotics is a very real physician concern regarding bureaucratic audits and punitive government regulations. In thirty-one states, doctors can be prosecuted by state and local lawenforcement agencies for oi/erprescribing narcotics to treat pain. The definition of overprescribing is often without basis in terms of contemporary professional understanding of pain management. Understandably, too many physicians are unwilling to prescribe narcotics, avoiding the costly office record keeping required for writing these prescriptions, not to mention the exceedingly expensive potential of defending themselves in a bureaucratic audit or legal investigation. Tragically for patients, many physicians are more likely to capitulate to their fear of punitive regulatory oversight, prescribing ineffective, non-narcotic medication. Interestingly, since 1997, twenty-five states have enacted laws to protect physicians and their patients. Unfortunately, the other states haven’t.

Fear of addiction should not prevent you from getting pain relief. In a survey conducted for the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society, published in 1999, 49 percent of those who had taken narcotic pain relievers said they were concerned about addiction. The vast majority of patients with pain from cancer or other causes do not become addicted to narcotics they take chronically for that pain (fewer than 5 percent become addicted, according to some data).

You, the public, must work to foster the commonplace, appropriate use of prescribed narcotics to treat pain, especially chronic pain. Within your communities, strive to alter irrational beliefs concerning addiction to prescribed narcotics. Prod the larger political system to liberalize regulations controlling the medical use of narcotics.

Balancing Pain Relief and Side Effects

In evaluating what kinds of side effects are acceptable, you have to weigh what is wrong with you, what medications and procedures can help your prognosis, what the chances are that your condition will improve on its own, and whether your pain is chronic.

Severe nausea and vomiting are not acceptable side effects of narcotics, but a little queasiness for a few days is. Most patients get used to most narcotic side effects in one week, except for constipation, which will not go away but can be treated. It is not acceptable to be drowsy or so sedated that you walk like a drunk. If you are on a new drug regimen and sleepy for a few hours of the day, but for the first time in years you have 75 percent reduction of chronic, severe, otherwise intractable pain, then the pain relief outweighs the side effects. That’s how doctors weigh side effects. It’s common sense.

Side effects from narcotics may be treated and often disappear with time because of tolerance. Nausea may be treated with antinausea medications like Compazine (prochlorperazine) and sleepiness may be counteracted on a long-term basis with amphetamines. Constipation is usually a persistent problem that may be controlled with a high-fiber diet, lots of fluids, a stool softener, and possibly a laxative.

The most serious side effect of narcotics—slowing of respiration and buildup of deadly carbon dioxide from inadequate breathing—is quite rare if narcotics are used as prescribed. Obviously if someone wants to commit suicide by taking all of their Percoset at once, they could die, or end up with brain damage from severe narcotic-induced depression of respiratory function.

Take the dose of the drug you need to control your pain. You should be given a drug that controls your pain with minimal long-term side effects. Realize that you can have side effects with one member of a drug family and none with another drug in that same group. Narcotics like Dilaudid, Percoset, methadone, codeine, and fentanyl skin patches (Duragesic) all may substitute for morphine and for one another. If one drug doesn’t work or isn’t tolerated, try another.

How to Use Narcotics Effectively

Preparations of morphine last from three to four hours, eight to twelve hours, or twentyfour hours. On the other hand, fentanyl patches (Duragesic) last three days.

The strength of a drug, in relation to how it is given, depends on the amount of drug that gets to the pain-modulating areas of the spinal cord and brain. When a drug like morphine is given by mouth, it is absorbed by the small intestine and goes to the liver, where it is broken down before circulating to the brain and spinal cord. When given intravenously, more drug gets into the brain and spinal cord before it is broken down, so a lower dose will provide the same pain relief as a larger dose given by mouth. Intraspinal injection of morphine permits still less of the drug to be given with good pain relief, because the drug is delivered close to its site of action—the cells with opioid receptors in the spinal cord that modulate or inhibit pain transmission.

In many difficult-to-control pain states, drugs can be used in combination. You may need a long-acting narcotic and a short-acting one, plus some other drug to work more specifically on neuropathic pain and one or several drugs to control the side effects of the narcotics (most commonly constipation).

In many cases of musculoskeletal pain—like a chronically painful back—a narcotic can be combined with nonsteroidal drugs like acetaminophen (Tylenol) to achieve better pain relief with less narcotic and fewer narcotic side effects. Narcotics and NSAIDs act on different pain-relieving mechanisms. As it turns out, adding an NSAID to a narcotic has a synergistic effect, which is more than an additive effect.

Prozac and similar antidepressants can accelerate the metabolism or breakdown of narcotics. Patients using these may require more narcotics, not because they are depressed drug addicts, but because their narcotics don’t last as long.

Physicians must know not only the duration of pain-relieving activity of various drugs but also their strength. Just as Scotch is stronger than sherry, and pure grain alcohol stronger than Scotch, Percoset is twice as strong as morphine, and Dilaudid six to seven times stronger than morphine. If, despite experiencing relief, a patient doesn’t tolerate 60 mg of morphine because of side effects or even a skin reaction to the drug, 30 mg of Percoset may be substituted.

Timing medicine correctly is as important as finding the correct medication. If you know a pill takes forty-five minutes to work, don’t wait until your back hurts to take it. Anticipate what you are going to do and take your medicine before you take a walk or play with little children or go shopping, so that the medicine will be in effect when the pain starts. This will also keep your dosage down. If a medication works for about four hours, watch the clock. Be aware that around four hours after the dose you should take it again before the first pill wears off. Otherwise, you are going to have pain in the middle of your Christmas-shopping spree and you will squirm until your pill takes effect.

Even here, however, there is room for an exception. Some people who are heavily medicated for chronic pain say it does slow down their thinking. They deliberately take short-acting drugs that they allow to wear off in order to give them periods when their thinking is sharper, despite the pain they experience. Except for these rare cases, I urge my patients to avoid the seesaw of taking medicine, eventually obtaining pain relief, and having it wear off, experiencing new pain, and so forth. Relief of chronic pain can take time and it involves communication and trust between doctor and patient, as well as patience. For example, of the drugs I have mentioned, it may take two months to figure out the proper dosage of Neurontin, because if the dose is raised too quickly, severe sleepiness may occur. It can take at least two weeks to experience the pain-relieving effects of anticonvulsants like Dilantin and Tegretol. Reaching the proper dose of tricyclics like Pamelor may take one to three weeks. That is a relatively short period, but not for a person suffering through side effects and waiting for pain relief.