Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS): The Black Hole of Neuropathic Pain

What the medical profession now calls complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)—a mouthful by any standard—was only recently changed from the previous name, reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD). Before that, this strange disorder was called by twelve other names, including minor causalgia and shoulder-hand syndrome. This musicalchairs game of names reflects the confusion surrounding the cause and treatment of this serious but enigmatic disorder. These names also reflect the unusual and sometimes dramatic tissue changes seen in the affected extremity.

The phenomenon was first described by a group of surgeons during the Civil War. (One of these doctors, S. Weir Mitchell, also described phantom-limb pain.) The doctors noticed that some soldiers with severe pain from hand or foot injuries would fill their boots with water or wrap their affected limbs in wet rags to “extinguish the fire.” Dr. Mitchell named the condition causalgia, from the Greek kausos (heat) and algos (pain) in 1867. This checkered history surrounding CRPS leaves no doubt that it is a kind of black hole of neuropathic pain.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) recently classified two different types of CRPS. Type 1, the syndrome formerly called RSD, does not involve obvious injury to the peripheral nervous system. Its deep, diffuse pain is brought on by infection, inflammation, surgery, heart attack, stroke, degenerative joint disease, burns, or prolonged nerve compression following the use of a plaster cast, to name but a few of its causes. Diagnosis is made five to six weeks after the onset of pain, because after this time injury to other tissues should have resolved. In contrast, Type II (formerly called causalgia) results from obvious peripheral nerve injury. In CRPS Type II, the areas of the body most often affected are the hand and foot, but pain can spread to involve the entire limb as well as unrelated structures. In about 85 percent of cases of CRPS Type II the pain persists for more than six months; in about 25 percent of cases it continues for one year or more.

Old studies suggest that CRPS rarely occurs in people under sixteen, appears to be more common in Caucasians, and is three times more common in women than men. In up to 15 percent of people, this disorder may follow trauma, with psychological factors playing an influential role in bringing it on.

The case of Maryann Dart exemplifies the terrible nature of this disorder. Ten years ago, a steel door crushed the fingers of Ms. Dart’s right hand. Four years and three surgeries later, she was finally diagnosed with reflex sympathetic dystrophy (as CRPS was then known) that continued to spread. Following several briefly successful blocks of the sympathetic nerves to her affected right hand, she had a sympathectomy, a procedure that interrupts the presumed painful hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system with chemicals, heat, or surgery. The procedure produced no long-term benefit, and her pain continued. She has become totally disabled and is now confined to a wheelchair. The pain has spread to her pelvis and groin, left hand, and left leg. It has affected the muscles of her eyes, causing a visual problem, and also affects her esophagus and bladder. The intensity of her pain is reduced while she is in warm water. She frequently goes to a warm swimming pool for some relief.

As in the case of Ms. Dart, people with CRPS often suffer through months, even years, of failed treatments before a true diagnosis is made and more appropriate therapy is begun. This frustrating course of trial and error reflects the many faces of the disease, particularly in its early stages. It can look like many other kinds of nerve pain from many different types of injuries and conditions, not to mention psychiatric disease. In up to 10 percent of cases there appears to be no obvious cause.

Symptoms

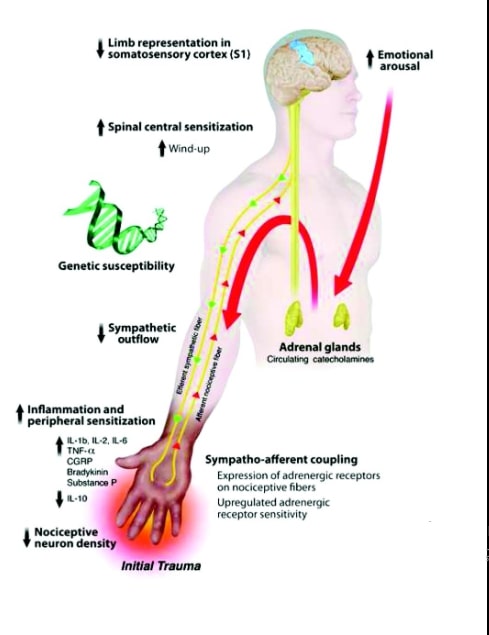

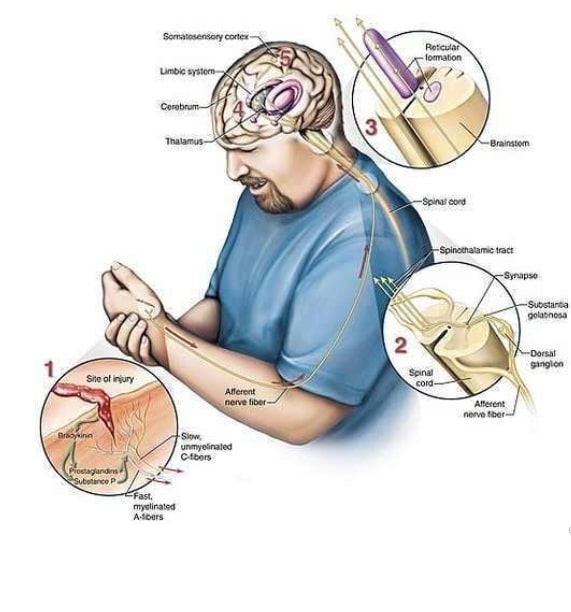

While the initial causes of the two types of CRPS may differ, the conditions have similar features, such as the horrible continuous pain in the affected areas, usually the extremities. The pain may feel like intense burning, occasionally in combination with an acute stabbing sensation. Some people describe knifelike, piercing, and throbbing pain, as well as deep aching. These flare-ups are out of proportion to the most innocuous stimuli, such as a breeze, a noise, moving an arm, or feeling anxious. A quick touch can set off a half hour of increased burning pain. The central nervous system is clearly hyperexcited or hy-persensitized. Moreover, the distribution of the pain often doesn’t follow the distribution of peripheral nerves, suggesting that the cause and mechanism for continuation and eventual spread of the pain involves more than the peripheral nervous system. The central nervous system may be important in the spread of this disorder.

Painful areas become swollen, red, warm, and dry. Later in the disease, the skin becomes sweaty, shiny, blue, and cold, and the nails get dry and cracked. The joints become stiff and fixed in contracted positions. Hands assume clawlike positions, muscles shrink, and the bones begin to lose calcium and become osteoporotic. Finally, the disease spreads up the limbs toward the central body. This process may involve limbs on the other side or even other parts of the body. Severe deformity of the affected extremities results in total physical and mental disability. The changes in the soft tissues and bones are thought to be caused first by augmented blood supply and later by diminished blood supply, presumably due to abnormal sympathetic nervous system activity.

Pain Management with Sympathetic Nerve Blockades

The management of CRPS usually involves a stepwise approach that depends largely on the severity and progression of the condition. All therapy is combined with active rehabilitation. Medication for neuropathic pain (anticonvulsants), tricyclic antidepressants, certain antiar-rythmics, narcotics, and even oral corticosteroids have been effective in relieving pain in CRPS. However, CRPS is considered by some to be a special type of neuropathic pain, caused or complicated by overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system.

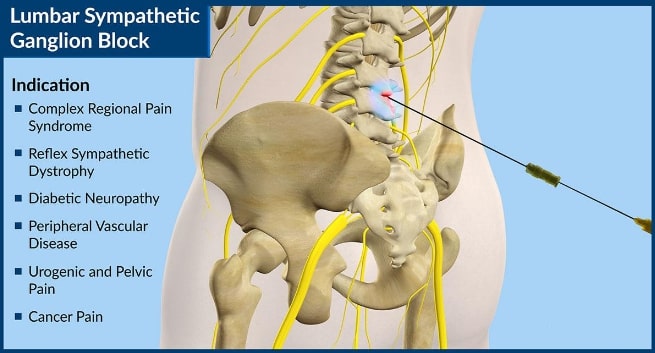

The sympathetic nerves travel with other nerves out of the spine, but their major role is not sensation or movement but controlling bodily functions, like blood flow and sweating, for example. Sympathetic nerves, when they fire, cause the muscles in blood vessel walls to tighten, which constricts the vessels, so less blood can flow through them. A limb affected by sympathetic overdrive could become cold and blue. If these nerves are at rest —not firing—the vessels they control open up, allowing more blood to flow into the limb, making it warm and pink. Blocking the sympathetic nerves with a local anesthetic will result in dilation of blood vessels, increasing blood flow and warming of the area supplied by the blocked nerves. In the block, the anesthetic is injected directly onto sympathetic ganglia, relay centers of the sympathetic nervous system. These are located next to the front of the spine in the neck, upper thorax, and lumbar area.

For those who believe CRPS is due to excessive sympathetic activity, reducing this overactivity should relieve pain and reverse disability. A sympathetic block results in a temporary, and a sympathectomy in a long-term, interruption of sympathetic nerve impulses supplying an area, such as an arm.

Sympathetic nerve blocks often provide pain relief for about three to four hours. The blocks may be repeated at regular intervals, with the goal of progressively dampening a vicious cycle of sympathetic nervous activity and pain. Unfortunately, the response to these blocks may vary even in the same person and there is also the risk of perforation of major blood vessels or other structures, such as the lung, depending on where they are performed.

If sympathetic blocks provide short- but not long-term relief, a sympathectomy may be considered.

Chemical sympathectomy is the injection of chemicals toxic to nerves, such as phenol or alcohol, onto the appropriate sympathetic nerves. Radiofrequency may be used to destroy the sympathetic nerves. Both chemical and radiofrequency techniques may last several months and can be repeated. Surgical procedures involve the removal of a piece of the sympathetic nervous system, producing a much longer lasting result.

Intravenous regional sympathetic blockade is a less invasive approach in which the affected limb is isolated with a tourniquet and a drug such as guanethidine is injected into the veins. Guanethidine inhibits or blocks sympathetic activity. The drug accumulates in a high local concentration during the twenty to thirty minutes the limb is wrapped in the tourniquet, so its antisympathetic effect is localized. More recently this treatment has been called into question and found in some studies to be no more effective than a placebo (saline injection), but it may be more effective when given early in the condition. An alternative approach to therapy, which appears to have had positive results, is the delivery of guanethidine through the skin of the affected area. This is done using a gentle electrical stimulation.

Unfortunately, these procedures all too often do not provide long-term pain relief (see below).

Oral Drug Therapy

Following the logic underlying the previous procedures, to the extent that the sympathetic nervous system is involved in the pain and sec ondary effects of CRPS, oral medication may be used to block sympathetic-nervous-system activity. These drugs include some that arc ordinarily used to lower blood pressure in people with hypertension. Some drugs diminish the activity of the sympathetic nervous system by blocking the ability of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter of this system, to bind to certain receptors. Drugs such as Inderal (propranolol), in dosages up to 320 mg daily, are prescribed to CRPS patients. Inderal can block the early-warning effects of low blood sugar and should not be given to diabetics being treated with oral medication or insulin. It also can worsen asthma. Other potential side effects of propranolol include low blood pressure, depression, feeling weak or faint due to low blood pressure, and impotence or inability to ejaculate. Drugs that block other receptors in the sympathetic nervous system include Minipress (prazosin) and Dibenzyline (phenoxybenzamine).

Another drug works by stimulating, not blocking, yet another type of sympatheticnervous- system receptors and paradoxically reduces, rather than stimulates, sympathetic activity. Catapress (clonidine), which is given as a skin patch, works in this fashion. All these drugs can make you feel weak or faint, because they lower your blood pressure whether or not they provide pain relief.

Another type of drug that works on the heart and blood vessels, Procardia (nifedipine), is also sometimes used in CRPS Type I patients. Procardia is a type of drug called a peripheral calcium channel blocker, which dilates the blood vessels and is thus effective in treating the aspects of CRPS attributed to decreased blood supply to an affected area.

Other Treatments for CRPS

For some severe cases, indwelling pumps or spinal-cord stimulation, mentioned later in this chapter, may help significantly. These measures provide pain relief so that physical therapy can be used to restore function to the affected limb. Even with treatment, symptoms remain present in up to 60 percent of people suffering from CRPS.

The Placebo Effect

Most if not all of the success of blocking or destroying sympathetic nerves in CRPS may be attributable to the placebo effect. Up to 60 percent of people with this disease respond for a short period to this scientifically questionable intervention. The placebo effect is the link between the mind and the body. Suggestion may cause the effect, but the body produces the pain relief underlying the effect. The naturally occurring opioid system appears to be involved in the placebo response. The placebo effect is partially blocked by drugs that interfere with the effect of narcotics—including the body’s natural opioids. Also, anxiety, which often accompanies pain, makes pain worse, pos- sibly by creating further spasm in muscles already tight from ongoing pain, among other things. Belief in a new treatment may reduce anxiety, relax tight muscles, and partially relieve pain. It is unethical and scientifically inappropriate to use placebos to determine whether or not your pain is real. A positive response to a water injection is a real effect and cannot differentiate real pain from fake. In fact, people with the worst pain are the most likely to respond to a placebo. Anyone can experience a placebo effect under the right circumstances. If one hundred people in pain are given a “very special pain reliever” (really water), at least thirty of them will note a real, temporary reduction in pain. The more they are in pain, the more they want a treatment to work, and the more they believe in the potential of the treatment to work, the more likely it is that a placebo effect will occur.

CRPS should be recognized and treated, like other neuropathic painful disorders, by competent pain specialists as early as possible so as to minimize the risk of sensitization of the central nervous system. The role for invasive and even pharmacological manipulations of the sympathetic nervous system, as opposed to other means of pain control in CRPS, must be further clarified.