Effective Opiate Prescribing

At the time of writing this article, there is estimated to be over 100 million Americans with chronic pain. The treatment of the majority of these patients will mostly happen by Primary Care Practitioners (PCP). Therefore, I have decided to author this article with the express intention of conveying my approach to effective opiate prescribing for the PCP.

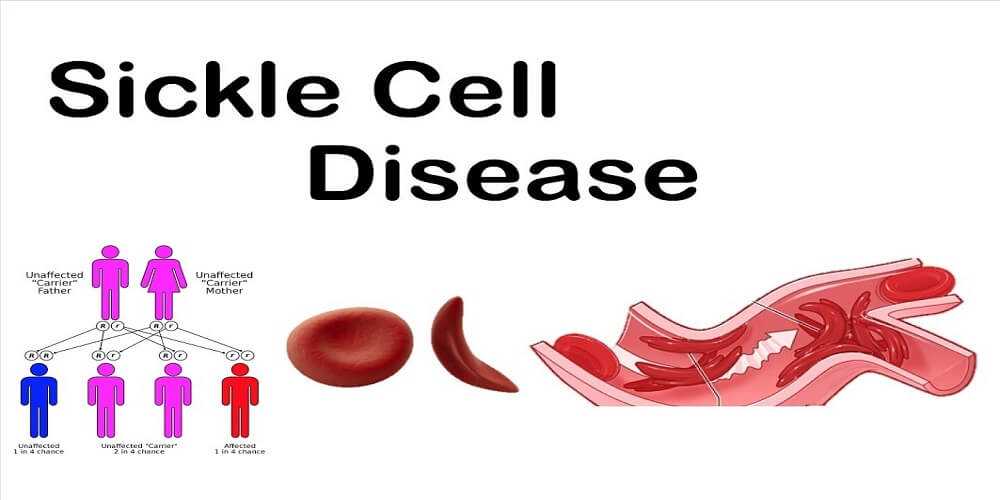

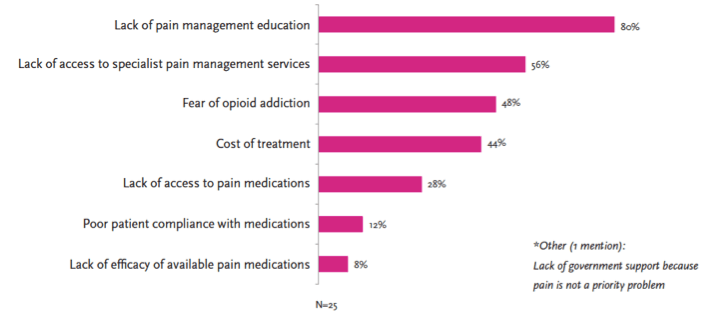

Ironically, the training in chronic pain management is woefully inadequate in the American medical system. Medical students get on average 5 hours total of chronic pain management teaching in an entire medical school curriculum. Even schools of veterinarian medicine teach many more hours of pain management than most medical schools in the U.S.

After graduating from medical school, most residency programs do not have any specific rotations in pain management. Whereas the most common malady that a Doctor of Medicine will encounter is chronic pain, it seems inconceivable that chronic pain management is not more emphasized by residency programs.

The number of pain management specialists is also inadequate. Most medical students readily understand that what is emphasized in their training is what is most valued when they graduate. Subsequently, a recent survey that polled medical students applying for residency programs showed that the least popular programs were pain management. The result is that there are not enough pain management physicians trained in the U.S. to meet the burgeoning need for the 100 million people in chronic pain.

What has happened in medicine is that other specialties related to forms of pain management have largely taken over the task of meeting the needs of chronic pain patients. Orthopedic Surgeons constitute the largest surgical sub-specialty that branches off into pain management.

The old saying, “Pick your specialist and you pick your disease” has a certain ring of truth to it when you consider pain management. An Orthopedic Surgeon will be naturally biased to lean towards surgical remedies for chronic pain. The patient that does not have a “surgical cure” will often need chronic pain medications for relief. Do you really think an Orthopedic Surgeon is going to manage a complex regimen of potentially habituating medications? I think not…

To add to this problem of undertraining to meet the need, Doctors who devote their practices to chronic pain management are often the targets of aggressive criminal prosecution by law enforcement. There seems to be little cooperation between medicine and law enforcement in this area. The result is a further reticence of physicians to become involved in the field. Who is left to meet the needs of over 100 million Americans?

I believe that what must happen is a movement must occur in medicine where PCPs receive intensive training in chronic pain management. The residency programs in Family Medicine, General Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, General Surgery, and Obstetrics/Gynecology must include regular rotations in Pain Management.

Furthermore, the fellowship programs in Pain Management must be opened up to all primary care residencies so that more people can be trained in the field. The real epidemic in America is chronic pain…even more pervasive than cardio-vascular disease. The needs of chronic pain patients are not being met.

The Truth About The Opiate “Epidemic”

I am sure you have observed all the media, political, and medical attention that the abuse of opiate pain medications has received. You have been told that the use of opiate pain medications for chronic non-malignant pain results in obligate addiction. You, like me, have heard many of the testimonies of parents who relate the death of their child to the irresponsible prescribing of opiate pain medications.

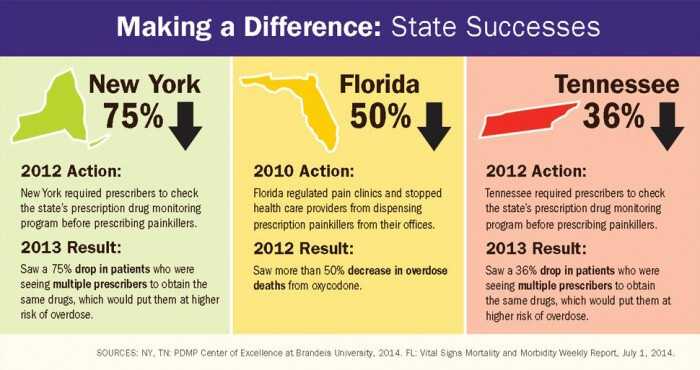

The prosecution of physicians who prescribe opiate pain medications makes for great press for law enforcement. The largely ineffective “War on Drugs” (illegal substances) has been replaced by the criminalization of physicians (a much softer target than illegal drug dealers). And yet, have we reduced the overall rate of addiction in the U.S.?

The rate of opiate addiction is approximately 15%. The incidence has not changed since the Civil War despite the aggressive attempts by law enforcement which began with the Nixon Administration. This is because addiction is a complex interaction of genetic, physiologic, psychologic, and social factors.

Consider the greatest social experiment of Heroin use in American history…the Vietnam War. At the height of the Vietnam War, 20% of all American soldiers deployed to combat regularly used Heroin (which was widely available in Vietnam). As the war drew to a close the American military leadership braced for an epidemic of Heroin addiction among the returning soldiers.

The “epidemic” never happened. Most of the returning GIs were able to stop using Heroin upon return to their families and friends. The stress of combat relieved, so was the use of Heroin. Only 3% of the Vietnam veterans who had used Heroin returned needing Drug Rehabilitation.

Reliable statistics on the rate of addiction for people who use opiate pain medications remains elusive. In people with no history of addiction the latest rate seems to be about 0.3%. When one reads most of the studies on this topic it becomes very evident that such studies are fraught with methodologic errors.

Even physician groups have formed that are attempting to limit the daily dose of opiates for chronic non-malignant pain. The Centers for Disease control is presently spearheading a movement in this direction. I have to wonder…are they reading the same studies I am? Where does this “opiophobia” originate from?

The “opiophobia” that has resulted is from a misunderstanding of the difference between habituation and addiction. Many of the medicines that physicians use in the practice of medicine cause habituation. In habituation the human body adapts to a chronically administered medicine. Tolerance and an abstinence syndrome (withdrawal) may result. This can happen with anti-hypertensive medications, certain cardiac medications, sleep medications, and anti-depressants.

In conclusion, the number of opiate complications that have been observed by the press and other media outlets are the result of what would be expected when physicians are trying to treat the chronic pain of so many people. If the percentage of people developing addiction has remained the same (which it has), then the increase in complications of opiate prescribing is due to the volume of prescriptions and not due to a change in the expected side effects of the medications themselves.

What is needed is better screening tools for already addicted people, for people who are addiction prone, for people who would be diverting their medication, and for people who could be safely treated with opiate pain medications. Law enforcement and physicians must find a way to work cooperatively as they are really on the same side.

The commonly held misbelief that all people on chronic opiate therapy are addicts is simply not the truth. The media and law enforcement will have to be educated on the facts…dedicated pain management physicians will have to be unrelenting in their support of their patient’s right to have relief of their pain.

The Mechanisms Of Opiate Pain Relief

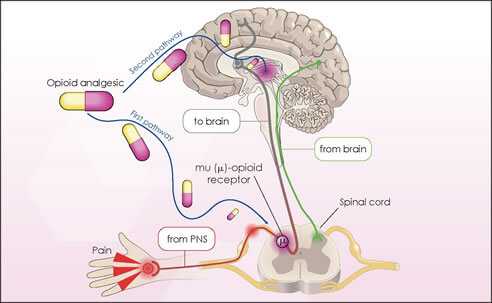

Every medicine that has any effect on the human body works through a receptor mechanism. That is, the medicine has a specific place where it attaches and exerts a physiologic effect. The receptor is often barely larger than a few molecules. Understanding how the medicine “docks” with any given receptor enables us to understand the mechanism of the medicine.

Receptors are very specific for the substances that attach to it. The number and type of receptors in any given place in the human body govern the effect a medicine will have. Factors that affect the receptor can enhance or diminish the effect of a medicine (without having to change the type or amount of medicine).

Opiate pain medicines operate through specific opiate receptors. The traditional teaching was that the “mu” receptor was the principal receptor of opiate pain medications. We now know that there are many receptors for opiates. There are even subtypes of the “mu” receptor.

The central nervous system is the principle site of action for opiate pain medications. As you might have surmised, that is where the majority of the “mu” receptors reside that affect pain. It is for this reason that opiates are so affective at reducing many different types of pain as all pain is really a central nervous system phenomenon.

When the “mu” receptor is repeatedly stimulated it begins to adapt. This adaptation results in the tolerance (requiring more medicine over time to obtain the same relief) and habituation (withdrawal) that is seen with this class of medications. This is an expected result of the administration of most chronic medications.

Tolerance and adaptation are governed genetically. Some people have a proclivity to develop addiction while others do not. The same treatment in 2 different people can result in addiction in one and not the other.

Furthermore, environmental effects (called epigenetics) can influence 2 people with similar genetic tendencies to adapt differently to the administration of opiates. There are no 2 people identical…even identical twins. Epigenetics can influence which genes are turned on or off. The net result is an interaction between the genetics and the environment…each are important when considering how a medicine will affect a person. Nature and nurture cannot be separated.

Opiates attach to “mu” receptors (and other receptors) and block the transmission and perception of pain. Though certain types of pain are better treated with opiates than other types, generally all pain is reduced to some degree.

Pain itself is a complex array of interacting physiology, so it can be expected that opiate pain relief may not only vary between people but within the same person. To make matters even more complicated, the physiology of a human being is always changing. Treating human beings for anything is really trying to hit a moving target.

In the next section I am going to use several examples of the opiate pain medicines that I used in my pain practice at Comprehensive Pain Consultants.

Common Opiate Medications

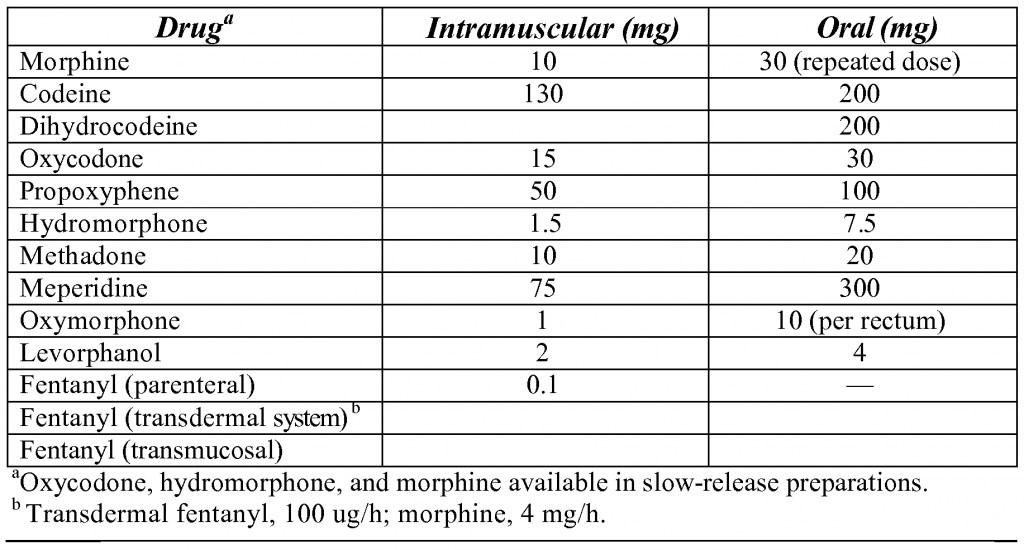

Though all opiate pain medications have similar mechanisms, the potency, duration of action, side effects, cost, route of administration, and availability varies widely for opiates (the above table depicts equivalent doses of the many opiates available). Since no single pain practitioner can be experienced with all the medicines available, I recommend that each pain practitioner become very familiar with at least one long acting opiate, one short acting opiate, one synthetic opiate, one intravenous opiate, and one transcutaneous opiate.

In doing so, the pain practitioner will be equipped to medicinally treat most forms of chronic pain. As new medications are being developed all the time, you may need to “switch-out” a medicine that you used commonly for a better medicine from time to time. You, as a pain practitioner, are a work in progress too.

* Long Acting Opiates

OxyContin (OC) is my long acting opiate of choice. It is really an “old” molecule (oxycodone) in a unique delivery system. The delivery system allows for the medicine to be delivered slowly over a 12-hour period when taken orally. Most people can achieve a measurable degree of pain relief taking OC every 8 to 12 hours orally.

I liken OC to the long acting insulin preparations. In a diabetic, blood sugar control is essential. By taking a long acting form of insulin, the top blood sugar levels are lowered generally. Dangerous sustained levels of blood sugar are avoided using long acting insulin preparations.

Similarly, when using OC, the pain level of any given patient is generally reduced. Persistently high pain levels are “cooled off” when using a long acting opiate such as OC. It is my opinion that the introduction of OC into pain management changed the effectiveness of treating chronic pain. It allowed pain practitioners to give large doses of oxycodone in as few doses as possible.

I found that when OC became available for pain management, my chronic pain patients were able to achieve a predictable level of pain relief that was sustained. The side effects were also better tolerated as the medicine was gradually released over time by the newly developed delivery system.

The starting dose of OC varies from person to person…situation to situation. In patients that have been on opiate pain medications, the starting dose will be higher. In a person who has never been on opiates the dictum is, “start low and go slow.” Each patient is individualized as to their starting dose and effective dose.

The effective dose to relieve pain with opiates varies from person to person. Opiates have no “ceiling effect” (the maximal dose at which additional increases in dosing will not give additional pain relief). For this reason (and others), some people require very large doses of OC. Some patients require hundreds, even thousands of milligrams of OC per day to obtain pain relief.

One patient’s dose should not be compared with another’s. A dose in one person may be toxic in another person. Each pain patient has to have their therapy individualized without value judgement. This is a major area of misunderstanding among physicians (for the reasons I have mentioned previously such as lack of training).

*Short Acting Opiates

Every pain patient has times through-out the day where their pain worsens. This is called “break-through pain.” The pain is “breaking through” the OxyContin coverage. Under those circumstances it is advisable to give a short acting opiate for covering the “break-through” pain (and not adjust the long acting opiate).

This, again, is similar to treating a diabetic. Even though a diabetic may be on a long acting dose of insulin, they will have “spikes” in their blood sugar from time to time (such as with a meal). For this reason, diabetics will often check a finger stick blood sugar before a meal and administer a short acting insulin preparation if the pre-meal blood sugar is too high.

This pre-meal administration of insulin “covers” the blood sugar “spike” often by using a graduated scale called a “sliding scale.” Not every pre-meal dose of insulin is the same amount (it depends on how high the blood sugar has risen). The “sliding scale” advises the patient on how much short acting insulin to take for a given pre-meal finger stick blood sugar.

In like manner, a short acting opiate is used for the “break-through” pain that occurs throughout the day. Every dose is not the same as it depends on the level of the pain. Can you see the similarity between pain medicine dosing and insulin dosing?

I think it makes most pharmacologic sense to use the same opiate molecule for the long acting and short acting form. In this way, the receptors are targeted maximally and you may expect the best pain relief. Furthermore, the side effects will be more predictable as you are utilizing the same molecule for pain relief.

Because of this, I used generic Oxycodone as my break-through short acting medicine. It has a rapid onset of action (within 45 minutes) and has a short 4-hour half-life orally (the half-life is how long it takes for 50% of the medicine to be metabolized). The “break-through” dose is often estimated at 10 to 20 % of the total daily dose of long acting opiate (though this varies widely too).

Generic Oxycodone is relatively inexpensive and widely available (unlike OxyContin which is very expensive). Because of the cost of OxyContin, insurance companies will often cap the amount of it they will cover. Furthermore, in the event OC is unobtainable (for instance, the pharmacy runs out of it), a patient can be easily converted to an equivalent dose of generic oxycodone.

*Synthetic Opiates

This class of pain medicines are important as a means of enhancing the effects of your opiate pain medicines (as they bind to a slightly different receptor), are an alternative to your other medications if you lose coverage (such as OC), and are generally well tolerated. I do not use them as a first choice as their pain relief orally is not as effective as the opiate compounds.

I used Methadone (MTD) as my choice for synthetic opiates. Most people are unaware that MTD is an effective pain medication (it is well known for its use in opiate detoxification). It was developed in Germany at the end of WW II. The patent was bought very cheaply by the U.S. Government which has resulted in it being the cheapest synthetic opiate on the market. Most patients can afford it even if their medical insurance would not pay for it.

That being said, MTD is a complicated medicine to use. It has an unusually long half-life (2 or 3 days) while providing pain relief for only 6 to 12 hours. This means that the side effects last longer than the pain relieving effect…tricky. There have been reports of QT prolongation (potentially increasing the risk of cardiac arrhythmia) with its usage…it is controversial whether the overdose deaths associated with it is due to this side effect.

More research is needed to establish whether MTD is really the cause of the overdose deaths by cardiac arrhythmia or simply due to the medication being taken improperly. It is easy to see how a patient that was used to taking their opiates in a certain way could mistakenly take too much MTD.

I frequently added a low or moderate dose of MTD to patients on moderate or high levels of opiates. MTD has a calming effect and may be preferred for patients that have an anxiety neurosis along with their chronic pain syndrome. It is usually dosed orally every 8 to 12 hours for chronic pain (or every 6 in lower doses).

*Intravenous Opiates

I am not going to discuss this class of opiate pain medications as it is beyond the scope of an introductory article on opiates. Suffice it to say, the use of this class of opiates for chronic pain will require a pumping mechanism of some sort (into the venous system or spinal cord). I used this method of administration in only a handful of very compliant patients. It is very effective and achieves excellent pain relief. I will write an article on this form of therapy in the near future.

*Transcutaneous Opiates

This form of opiate administration is particularly useful in the event a patient cannot tolerate an oral opiate. Patients with intractable vomiting who have chronic pain, patients with a Gastric Bypass (which changes the pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of an orally administered medication) with chronic pain, and non-compliant patients with chronic pain may all benefit from this type of medication.

For this route of administration, I occasionally used a compound called a Duragesic Patch. It is actually a delivery system where an adhesive patch has the synthetic opiod Fentanyl impregnated into it. Fentanyl has its most common usage as a pre-anesthetic agent in surgery (given intravenously when used in that manner). Its half-life is quite short intravenously (10 to 20 minutes).

However, when used in the Duragesic Patch format, this medication has a 3 day delivery period (the patch is changed every 3 days). This again demonstrates that the delivery system that any given opiod is placed into can affect the duration of action of the medication.

The challenge with this type of delivery of medication is the mechanics of wearing a patch. Patients with oily skin, dry skin, and sweaty skin may all find that the patch does not adhere well. If the patch falls off, reapplying the same patch may not duplicate the proper absorption (as when first applied).

Furthermore, the onset of pain relief after applying the patch may take several hours as the medication builds up in the bloodstream. Initiation of this form of medicine requires that a chronic pain patient have an available supply of short acting medicine when the patch is first applied.

Due to the challenges of wearing a patch (and its high cost), I used this form of pain management infrequently in my practice.

Let me continue my discussion on the art of effective opiate prescribing by discussing the potential side effects of this class of medication.

Side Effects Of Opiate Medications

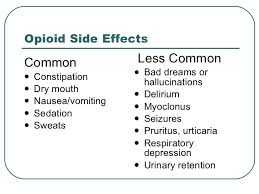

Any medication of effect will have side effects. In fact, “side effects” are not really “on the side” but are exaggerations and extensions of the effects of the opiate medication. When it comes to medications in general, the higher the dose the more likely a “side effect” will occur.

Opiate medications are actually some of the safest medications that can be given to a patient. For instance, generic Oxycodone has a pregnancy rating of “B” when taken during pregnancy. That means that the likelihood of birth defects occurring as a “side effect” of the medicine is less than that of Motrin (which has a pregnancy rating of “D” after 30 weeks of pregnancy and “C” before 30 weeks of pregnancy).

The major “side effect” of chronic pain patients maintained on opiate pain therapy is constipation. This is easily addressed by taking a stool softener and/or laxative at regular intervals while on opiate therapy. Opiates slow down the peristaltic contraction of the bowel which causes the constipation.

The media gives the most attention to overdose and addiction as side effects of opiate pain medication. As regards overdose, the very term itself depicts an incorrect taking of the medication. Would any medicine be allowed if judged on the overdose effects?

The issue of overdose with opiates is not an intrinsic medication defect as much as it is an abnormality of the person taking the medicine. Irresponsible behavior does not occur in a vacuum. The cases of overdoses with prescription opiates needs to be addressed at its source…the patient.

Patients need to be followed carefully for reckless behavior. This is not easy and is very time consuming. At Comprehensive Pain Consultants, I spent 2 hours each morning before office hours collecting intelligence data on patients for polypharmacy (and continued same throughout the office hours). I even hired a full time intelligence officer to proactively survey patients for addictive and diversionary behavior.

Monitoring Patients On Opiate Pain Medications

Because of the risk of very creative and nefarious patients finding their way into a pain management practice, Comprehensive Pain Consultants (CPC) had a very comprehensive system to screen and follow chronic pain patients. Our system included the following:

- A screening process that required every new patient to be referred by a physician, 6 months of progress notes outlining the previous pain management, diagnostic studies that support the reason for chronic pain, and hospital records of surgical procedures that were performed relevant to chronic pain.

- Frequent Urine Drug Screening for illegal, unprescribed, and prescribed medications.

- Witnessed urine sample collection when sample contamination was suspected.

- Observation of behavior from the time of arrival in the CPC parking lot until leaving the office.

- Signing of an extensive narcotic contact at each visit.

- Utilization of a software program (AthenaNet) for the possibility of Doctor shopping. It was able to identify if patients were receiving prescription pain medications from other Doctors (they had to use their medical insurance for this to be detectable). The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania does not have a central registry for patient prescriptions that is accessible by practicing physicians.

- Installation of digital cameras in all common areas of CPC with a permanent recording.

- Frequent patrolling by CPC Intelligence officers of the CPC grounds and street parking.

To my knowledge, there was not a practice in our region (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) nor in the U.S. that had such an extensive system for identifying addicts and diverters.

Discharging a Patient On Opiates And Patient Abandonment

The issue of patient abandonment is very real in the field of chronic pain management. As a board certified specialist in General Internal Medicine, it was very unusual to discharge a patient from my practice. When I focused my medical practice on chronic pain management I discovered that a particular type of patient had infiltrated into CPC.

These people (a minority by the way) were nefariously creative in just how they could justify their chronic pain. As there exists no diagnostic study that actually measures pain, the testimony of the patient is the only way to assess whether they are actually experiencing pain.

I have observed the sometimes callous way that pain management physicians discharge suspicious pain patients. This is often done on the basis of over-interpretation of urine drug screening (UDS), on the way a patient looked, or even based on a “sense” that a pain doctor had about a patient. The medical literature supports a different approach.

Most patients are non-compliant to some degree. Patient compliance studies have shown that, in the best of circumstances (such as in a research study), patients will be 60% compliant with their medications. I, therefore, devised a system that probated low risk patients.

If a patient was shown to be using illicit drugs, they were probated for an 8-week period. During that time, they came to the office every 2 weeks for a UDS. If their UDS violated the terms of their narcotic contract they were discharged. Most patients were able to stabilize their UDS and be readmitted into the practice. The patients were given 2 week prescriptions of their pain medications during probation. The dose and frequency of the medicine was “frozen” at the level they were at when the infraction occurred.

Immediate discharge from the practice occurred when a patient was discovered to be diverting their medications. In the event that a patient was discharged for other than diversion (for possibly showing addictive behavior) they were given a 2 week to 1 month “bridging prescription.” This allowed them to find another pain management practice without having to face withdrawal from their medications (and worsening of their chronic pain).

Nearly all patients that demonstrated persistent addictive behavior were discharged to Drug Rehabilitation (DR). We had several DR centers that we referred the patients to. In the event a patient successfully completed their DR, they could be re-evaluated for possible readmittance to CPC with modifications. Readmitted patients were automatically entered into an 8-week probation to observe their behavior.

It was the policy of CPC that, since addiction is diagnosed by witnessed behavior (see the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Psychiatry – V), nearly no single addictive behavior would be allowed to initiate a discharge. I also followed a policy that drug addiction by itself does not disqualify a legitimate chronic pain patient from pain management.

The CPC system worked quite well. No patient was ever abandoned for medication non-compliance or addiction. Only patients that were clearly suspected of breaking the law regulating the use of scheduled medications were immediately discharged. Rumors, anonymous phone calls, accusations etc. were not criteria for suspicion of diversion.

A patient who was discharged for diverting their medications could only be identified by direct observation of having done so by a reliable observer. A reliable observer constituted a law enforcement officer, a member of the CPC staff, a pharmacist, another practitioner, or myself.

I believe CPC had the most ethical, thorough, and fair system of identifying patients who were suspected of being addicts or diverters. No patient was discharged without abundant objective evidence supporting my decision. CPC never had any patient complaints about the fairness of our system. The CPC system was consistent with the highest standards of patient care and never abandoned a legitimate pain management patient.

Summary Remarks

This is a rather extensive article that outlines the CPC format for effective opiate prescribing. I have not only reviewed the introductory pharmacology for doing same but I have also detailed the system that I created at CPC for identifying addiction and diversion.

For all its innovation and completeness, the CPC system of pain management was not perfect. Until closure of the practice 1/16/2013, CPC still regularly identified patients who had become addicted or were diverting their pain medications.

Pain management is not a perfect science. Identifying addiction and nefarious patients takes time and observation. Before closure of CPC, I was exploring additional innovations to continue to upgrade our system. Polygraph testing all new patients, digital video recording of all patient visits, and a paperless-debit/credit card only means of payment by the patients for their office visits were upgrades that were being actively explored.

All in all the patient with chronic pain must not be forgotten. Most of my patients were suffering greatly from their chronic pain. The opportunity for physicians to impact the lives of people is no greater than in the field of chronic pain management.

To cure some, alleviate many, and comfort all is my credo. It is the reason I became a Doctor.

Wishing you joy and healing,