Living with Sjogren’s Syndrome

Sjogren’s affects people so differently and the extent of the disease usually determines the modifications necessary. This article is about maintaining your quality of life with Sjogren’s syndrome. People with little pain or fatigue do not have to pace themselves in the way that people with either or both do. Age and stage of life make a difference too. Although the actual symptoms and emotions that accompany a diagnosis of Sjogren’s may not vary with age, the demands of life are different at thirty-five than at sixty.

Limitations are difficult when you are juggling multiple roles: parent, worker, spouse, and sometimes the caretaker of aging parents with health problems of their own. It makes a difference if you get sick and your family and friends cannot relate to your experience because you are young. In midlife, when people begin to experience health problems, there is more understanding of what it means to have an illness, even if no one has heard of Sjogren’s syndrome.

Listen to Your Body

A healthy body takes you where you want to go. Healthy bodies, even those that have reached middle age and beyond, usually move through the day with ease, prone to some aches and pains now and then, prone to afternoon postprandial fatigue, but resilient just the same. Healthy bodies move through a crowd without bringing home an infection that will take weeks to heal, and a healthy body can push itself when the need arises. One healthy friend of ours noted that she gets tired when she pushes herself too far, but it doesn’t take her much time to recover. As we write this, we are in awe of what a healthy body can do, with little tending. Sjogren’s can make a young person feel old. A healthy seventy-year-old may be able to do more than a person of thirty-five or forty with Sjogren’s, and do it with ease.

Listening to your body means paying attention to things you may not want to hear, such as early warning signs of wear and fatigue. Gains from getting one or two more things done are offset by the penalty for doing them. Getting to know your body becomes an important survival tactic. We aren’t suggesting that you constantly check yourself. There’s no need to take your temperature (either literally or figuratively), morning, noon, and night. We mean that you need to get to know your body, and what it can and can’t do, in an intimate and personalized way. There are times when life circumstances may require more than your body willingly permits, and at such times, do the best you can and make as many adjustments as you can. If you listen to your body, you will find your baseline. If your Sjogren’s is not stable, this becomes more difficult. It may take extra time to adapt to change.

Listening to your body is a two-part proposition. Once you think you have a sense of what you can do, you have to pay attention to it! Think of your body as you would your finances. The credit card bill comes at the end of the month and you have to find a way to pay. So it is with your body. If you push it too far, it will let you know and there will be a price to pay. What you can do may change on a daily basis.

Watching Your Limits

It’s easy to say “listen to your body,” but what about earning a living, taking care of children, going to school, managing a relationship, or taking care of aged parents? There are serious health consequences for pushing yourself beyond your limits. Here are a few suggestions:

♦ Make small changes if big ones are not possible. See how your body responds. Small changes do add up.

♦ Have a contingency plan. Ask yourself what you would do if you couldn’t do what you are currently doing. Review and revise this as circumstances change.

♦ Write down your plan in a notebook and put that book away in a safe place. It’s always better to make alternative plans and not use them than it is to have to make important decisions in an emergency.

♦ Push yourself only when absolutely necessary and for the shortest time possible.

Having Sjogren’s necessitates choices that a healthy person doesn’t have to make. A woman in her thirties with young children at home told us she was contemplating a job change. She had two job offers. One was more interesting, but it was farther away and would require more travel time. The other was closer to home, but less interesting. She thought she would probably take the one closer to home, because it would enable her to go on working for a longer period of time. Here was one woman, like many, whose career was affected by her illness.

You have to make choices all the time. Some of those choices need to take into account that you have Sjogren’s. For example, if you have a choice of health plans at work, take the most comprehensive one that you can afford and that gives you the most choice. It won’t be the cheapest. Don’t try to save money by overlooking the disability insurance if it is optional. Purchase whatever disability insurance you can. Having a chronic disease is a wake-up call to the fact that unpleasant things do happen, and it pays to take a long view.

Containing Flares

A flare is an exacerbation of symptoms. Joints hurt more, muscles ache, fatigue increases, and there is no other obvious cause. For some people, it is difficult to differentiate a Sjogren’s flare from the flu or an infection that produces nonspecific symptoms. Flares may trigger depression, and it is difficult to distinguish between the symptoms of depression and those of a flare. Doctors can have trouble differentiating too, so when you go in and say “I’m feeling worse,” they may take some routine lab tests, and if those don’t provide any more specific clues, they may adopt a “wait and see what develops” attitude. Once a flare begins, it’s difficult to say how long it will last. Some flares last a few days. Others persist for weeks.

Some flares occur after a specific incident. Stress can provoke one, as can viral or bacterial infections and some medical procedures. The infection ends, but sometimes symptoms persist and you continue to feel worse than usual. You may run a low-grade fever.

Fluctuations can also occur within a flare. For a few hours, a part of a day, or even for a day or two, you may feel better. Just as you begin to think it’s over, it comes back.

Once a flare begins, it is hard to make adjustments. No matter how limited you are, you probably make plans based on what you expect to be able to do. When you can’t do what you expected, you face the consequences of not getting it done, and also your feelings about not being able to do what you had planned.

“Will this ever go away?” is a question frequently asked during a flare. In most cases, the answer is a hopeful “Yes, this too shall pass.” First you have to get through it. Learn what you can about your body from the flare. If it occurred after some specific activity, think about ways you might moderate this activity in the future. Remember that sometimes cause and effect isn’t so obvious. Before you decide that a vacation with your in-laws caused a flare, think about the full range of factors involved: extra energy getting ready for the trip, the stresses of travel, unfamiliar surroundings, changes in climate, and so on.

Once a flare occurs, simplify. Give in and let your body rest as much as possible. Take time off from work, sleep extra hours, let the housework go, and order take-out or let someone else cook. Don’t burden yourself with guilt. Stare at the television if you need to, take a warm bath, read a book. The idea is to get through it as quickly as possible. Flares are always unwelcome guests. Think of them that way and look forward to the day they go home.

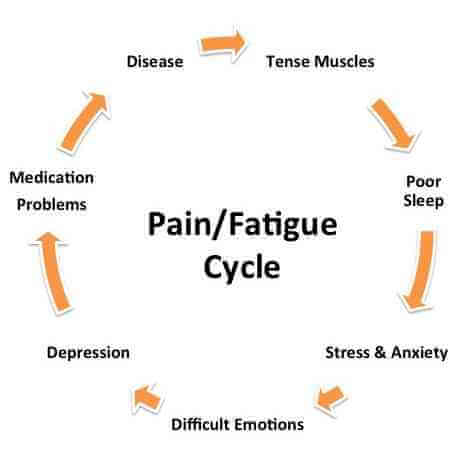

Coping with Pain

Pain is part of Sjogren’s syndrome for many people. It may be the result of fibromyalgia or it may be part of primary Sjogren’s. It may be muscle or joint pain and may be acute and chronic. People with Sjogren’s may have a variety of ovedapping conditions that cause pain, such as fibromyalgia, arthritis, tendinitis, migraines, or irritable bowel syndrome.

Pain control can be an arduous process. It may take multiple trials of a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) to find one that works. For some people, the side effects may be as bad or almost as bad as the symptom the medication is meant to control. Multiple medication trials may be required, which becomes excruciating to someone who just wants his or her pain to go away. Sometimes it is difficult to keep trying. As author Suzanne Skevington notes, “unless pain sufferers have a reasonable expectation that if they take a particular course of action that will be able to directly control their pain, they are unlikely to attempt it” (Skevington 1995, pl44). People who feel that they will ultimately be able to get their pain under control are likely to be more tolerant of the unpleasant side effects than those who fear that they will not be able to control their pain (Skevington 1995). Inadequate pain control may be worse than having no control at all, which makes perseverance all the more important.

Education and behavioral changes are important components of pain control. Selfmanagement courses that combine information about arthritis, exercise and relaxation programs, and information on nutrition and medication use have been found to decrease pain and depression significantly, and the results were sustained over time. Four years after patients had entered a program, their pain was still 20 percent less than at the beginning of treatment (Skevington 1995). The combination of education and behavioral changes appeared to be more effective than either education or behavior change alone.

Chronic pain can lead to an increase in depression, and depression may lead to a decreased ability to cope with chronic pain. In one study, the researchers found that people with inflammatory disease had higher levels of pain after an unpleasant day (Skevington 1995). The same researchers found that people who had high levels of social support were likely to have less pain and depression after something unpleasant occurred, indicating that social support can act as an important buffer.

People with chronic pain may feel increasingly depressed if they sense that other people are withdrawing or do not understand their experience, or fail to appreciate the limitations and restrictions of living with chronic pain. Kleinman (1988) notes that depression that results from chronic pain may actually be the result of demoralization. This is exacerbated if physicians fail to recognize the extent of your pain and don’t treat it adequately. It is therefore extremely important to discuss any uncontrolled or poorly controlled pain with your physician and to have the same conversation repeatedly, if necessary.

Coping with Fatigue

Fatigue, in all its textures and nuances, is part of life for many people with Sjogren’s. The fatigue that accompanies Sjogren’s has been characterized as awful, terrible, bone-tired, bone-weary, toxic, encompassing, poisonous, and noxious. It invades and engulfs, attacks, assaults, inundates, swallows, and entombs. It is a fatigue that makes some people feel as if they are a piece of laundry. They “crumple and fold” like a limp bed sheet or a towel on the floor. In his book on lupus, Robert Phillips says people with lupus (and Sjogren’s) feel “as if someone had pulled the plug” (Phillips 2001, 53). We agree with him.

One of the difficult things about Sjogren’s-related fatigue is that it comes on so swiftly. You can feel normal in the morning, and as if there were lead weights attached to every limb by noon. The fatigue may be accompanied by an increase in joint or muscle pain. Fatigue can be a constant companion. We have each had the experience of waking up in the morning and feeling that someone had poured molten lead into our bodies overnight. When the fatigue is sudden, it’s difficult to continue what you are doing. It’s hard to concentrate. In the middle of a meeting or some other activity, we have each become too tired to talk. We have put down writing this manuscript in the middle of a sentence.

It is possible to be incredibly tired and still appear normal. Because pain and fatigue are invisible, most people won’t know what you are feeling unless you tell them. When someone knows you well, they learn to pick up subtle signs. “Do you want to go home. Mom?” one of our children said recently after an afternoon of shopping. After so many years, he had learned to recognize when his mother was ready to fold. Mom gratefully handed her grown-up son the car keys.

You may be sensitive to changes in either temperature or barometric pressure, or both. You know that a storm is moving in while the sky remains blue and cloudless. When the temperature shifts dramatically or the barometric pressure rises or falls, you can feel a corresponding wave of fatigue or feel released from fatigue.

Other medical causes of fatigue should be ruled out. Fatigue is a nonspecific symptom that accompanies many different conditions. Among these are diabetes, thyroid conditions, anemia, infection, cancer, and other autoimmune diseases.

Fatigue can be a side effect of medication, but medication can also help alleviate fatigue. A variety of medications that work for pain also help alleviate fatigue: some of the NSAIDs, Plaquenil, and prednisone are examples. Fatigue can result from poor nutrition (because you are too tired to cook or shop) and, paradoxically, from inactivity. Fatigue may also be the result of depression.

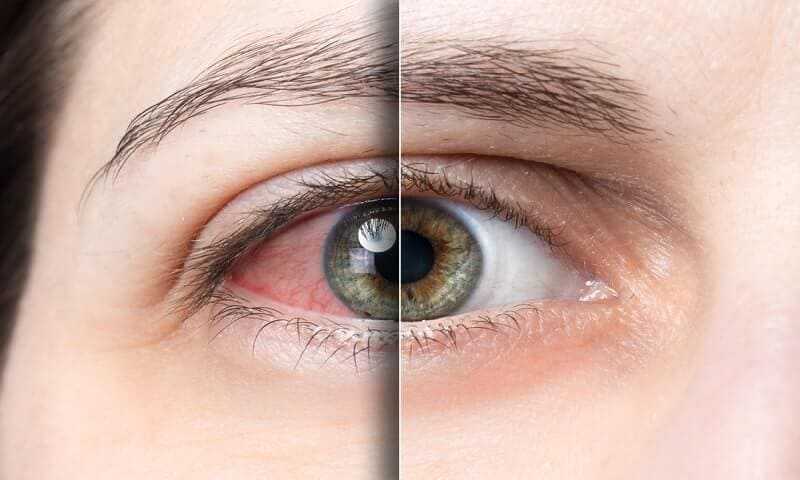

Dealing with Dryness

Dryness can affect the quality of your life. You may have very dry eyes, but your mouth is less dry, or vice-versa. You may not be able to get through the day without large amounts of water and eyedrops, or get through the night without waking up to take a drink or put ointment in your eyes. Your eyes may be sensitive to light, and you may avoid driving or riding in cars or walking in the wind because it aggravates already dry eyes. Dryness can restrict the amount of time you are able to spend working at a computer or reading.

Dryness can hit your pocketbook hard, too. Eyedrops, special mouth rinses and toothpastes, and tiny tubes of eye ointment add up to a significant annual expense.

If dryness prevents you from sleeping through the night, make sure the humidity in your home is adequate. There are inexpensive thermometers that measure both temperature and humidity. While forty percent humidity is desirable, in certain parts of the country you are lucky when you can humidify your home to more than 30 percent. Remember that both heat and air-conditioning are drying. Unfortunately, a humidifier or humidification system can be a good source for both mold and bacteria. Whether you have tabletop humidifiers or a built-in system, careful maintenance is essential.

Getting Enough Rest

People with autoimmune diseases need extra rest and often don’t get it. You may have trouble falling asleep or staying asleep and wake up feeling as if you haven’t slept at all. Extra rest may mean needing to take breaks during the day.

You may not do well with long periods of sustained activity. Whenever possible, try to rest. One friend with Sjogren’s divides the day into three periods, morning, afternoon, and evening. If she does something in the morning, and knows that she has plans for the evening, the afternoon is designated as mandatory rest time. If she has to do something in both the morning and afternoon, she is tired by four or five, and needs to rest all evening. When she is not feeling well, she might do something in the morning and rest for the remainder of the day. Another friend prepares dinner early because she needs to rest in the afternoon.

Resting is difficult when you have a job, young children, or both. Sometimes a half hour or forty-five minutes will help. Twenty minutes is better than nothing. Try to carve out some time when you can just sit down and recharge.

How Much Should You Push Yourself?

If you never pushed yourself, life would be devoid of challenge, as well as boring. You may push yourself to do new things, to accomplish something that seems just beyond your reach, or to change from one situation to something else. If you push yourself too often and too far, you pay the price. It’s important to achieve the right balance. It’s like walking a tightrope. Lean too far to one side, and you compromise what you can do with your life. Lean to the other, and you will find yourself exhausted and in a state of constantly needing to recuperate. How far you should push yourself is therefore exceedingly personal. It relates to what we said earlier about listening to your body. Stay as active as you can without paying too great a price. Sometimes it is necessary to do something that is a challenge. You may be able to do more and go further than you think, but challenge yourself gently.