Myofascial Pain

Clinical Presentation

Myofascial pain, sometimes known as myofascial pain syndrome or regional myofascial pain , is a condition whose diagnosis is based on clinical findings. Myofascial pain is defined as a pain syndrome that exists in a region of the body, and that is not caused by a physical problem within the spine or nerves. The muscles and supporting muscle tissues may be tender or in spasm, but these changes are not the primary cause of the pain. The pain of myofascial pain is thought to originate from abnormal signals within the nervous system. As such, myofascial pain is a type of neuropathic pain.

No imaging or diagnostic tests prove the diagnosis. Some believe that myofascial pain is simply a psychosomatic pain syndrome, but this is not in keeping with the scientific and medical literature available. In other words, myofascial pain is a well-established clinical entity that is too often underdiagnosed or misunderstood by physicians and other health care practitioners. In this setting, the clinician may simply prefer to state that no medical basis exists for pain rather than admit that he does not understand the basis for the pain.

Myofascial pain generally presents in one region of the body and, with regard to the lower back, myofascial pain can present as a diffuse low back pain, as a regional pain on one side of the back or the other, or as pain with radiation into the gluteal and proximal leg musculature.

Patients who suffer with myofascial pain may experience exacerbations and remissions of pain. Very often, no clear precipitating or palliative features to these exacerbations and remissions are present. Patients often remark that the pain “seems to have a life of its own.” This distinguishes myofascial pain from more mechanical and situational pain syndromes such as a lumbar disc herniation or lumbar stenosis.

Pain often is described as deep, aching, and sometimes burning. Pain frequently awakens the patient from sleep. The patient often feels somewhat better when he is more physically active.

Myofascial pain may be the result of repetitive trauma or overuse, or it may be a response to a more singular traumatic event. For example, some patients may develop myofascial pain following a sudden accident. The difficulty in making this diagnosis is that the severity of the trauma per se does not predict whether someone will develop myofascial pain. For example, a minor car accident may become the inciting event for severe myofascial low back pain. Thus, it is the patient’s response to the trauma or repetitive traumas that determines the outcome, and not the physicality of the trauma in and of itself. This response is both physical and physiological, which means that the response has to do with the musculoskeletal system and the emotional-cognitive processing system, that is, the mind-body.

Myofascial pain may exist as a continuum with another condition known as fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia is a more diffuse pain syndrome, affecting multiple joints or multiple muscular trigger point areas in the arms, legs, neck, and trunk. Some patients seem to move in and out of a fibromyalgia presentation and myofascial pain presentation over time.

Myofascial pain can coexist with other musculoskeletal conditions. For example, some patients may have radiographic evidence of lumbar stenosis, but their clinical presentation suggests a myofascial pain syndrome. Similarly, patients may have a herniated lumbar disc, but they do not present with the characteristic symptoms of mechanical pain from a disc herniation. Sometimes, the body responds to the lumbar stenosis or herniated disc in such a manner that it develops a transformed pain syndrome. Clinicians must learn to rely on making a firm diagnosis based on the clinical presentation. Imaging studies alone are insufficient to make a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Myofascial pain can be a short-lived response to a traumatic event, or it can become a more chronic condition. When myofascial pain becomes chronic, other markers of disability often are present, from a psychological, social, and physical point of view, and all these factors must be considered in treating the patient.

Cause of Myofascial Pain

Various explanations are given for myofascial pain, but no one unifying explanation exists for this condition. With regard to the lower back, the muscles involved often include the deep rotator muscles, the iliopsoas, the gluteal muscles, and piriformis. Tenderness to palpation may be present, but this is not always the case. The muscles generally have a maladaptive state, with decreased flexibility, abnormal consistency, pain with contraction, and a hypersensitive response to internal and external triggers.

Myofascial pain is a neuropathic pain condition, meaning its genesis lies in a dysfunction of the nervous system. Myofascial pain has a remarkable biochemical and physiologic similarity to migraine. Migraine is a disorder of the trigeminal vascular complex—the nerves and blood vessels that innervate the brain and head. In migraine patients, a hypersensitivity exists in this entire system, with abnormal “pacemaker” activity in the brainstem. This results in pain signals and regional inflammatory chemicals being generated, despite the fact that no localized trauma is present to cause such pain. In some migraine patients, the pain becomes transformed into a chronic, daily headache.

Myofascial pain has a similar presentation. Abnormal pacemaker activity occurs in the brainstem, and a hypersensitivity response is triggered between the brainstem and the region of the spinal cord that mediates the local pain response. Abnormal pacemaker activity means that a particular brain circuit sends signals unusually fast or slow. The brainstem pacemaker is commingled with parts of the brain that sustain emotional and cognitive activity. As a result, patients who suffer with myofascial pain may note a relationship between uncompensated stress and pain response.

The serotonin and norepinephrine pathways are particularly involved in the expression of myofascial pain. The serotonin and norepinephrine centers are located in the brainstem and project widely to multiple brain and body areas. Serotonin and norepinephrine are the chemical mediators of multiple physical expressions, including depression, anxiety, and irritable bowel syndrome. Thus, it also comes as no surprise that patients who suffer with myofascial pain may also suffer with depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, migraine, or some combination thereof.

Physical Examination

The musculoskeletal examination may be rather unremarkable in a patient who presents with myofascial pain. At times, areas of specific trigger points may be present, and pain with resistance to certain trunk movements may be present. The neurologic examination is normal. Indeed, it is the paucity of physical findings that has led some clinicians to doubt the existence of myofascial pain and to suggest to a patient that the pain must be “in your head.”

Imaging and Diagnostic Studies

Patients with myofascial pain have no abnormalities in imaging or other diagnostic studies that correlate with or explain their pain. Incidental abnormalities may be present, and this is often the case when patients undergo an evaluation. For example, a patient who presents with 1 year of low back pain and who undergoes a lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be told that he has degenerative discs or even a disc herniation. Because of these abnormalities, and because there is no other “objective” explanation otherwise for pain, the patient and clinician may then embrace the idea that the pain is anatomically generated from these abnormal discs. This can then lead to a cascade of unsuccessful treatments directed at these discs.

Treatment Considerations

Nonsurgical

Patients with myofascial pain benefit from a multidisciplinary approach. The first and sometimes most important aspect of treatment is to evaluate the patient and to assure him that he does have real physical pain. Too often, patients with myofascial pain have sought numerous medical opinions, have been told that nothing is wrong, and then begin to doubt themselves, the medical profession, or both.

Routine physical therapy often exacerbates myofascial pain. Physical therapy is too often a simplistic combination of ultrasound, electrical stimulation, and cookbook-type exercises. If the abnormal tension, contractility, and hyperresponsiveness of the musculature are not addressed, then exercises can worsen the pain.

Skilled hands-on therapy, including spinal manipulation, physical therapy with a focus on myofascial release and craniosacral technique, and acupuncture can help to reshape the maladaptive muscular response of myofascial pain. This type of treatment in and of itself can be extremely beneficial.

Patients often benefit from medication. One of the most successful medications for myofascial pain is amitriptyline, which is an old-fashioned antidepressant medication that nonspecifically increases the availability of norepinephrine and serotonin. This medication promotes sleep, and patients with myofascial pain are often sleep deprived. Amitriptyline generally is prescribed in a low dose, 10 mg to 25 mg, which is lower than the therapeutic dose required to treat depression.

Anticonvulsants sometimes are useful in treating myofascial pain, especially when the pain has a burning component and when the pain has become severe. The choice of anticonvulsant depends on other symptoms that the patient is experiencing. Some anticonvulsants help to promote sleep, some anticonvulsants are associated with weight loss, and others are associated with weight gain. Newer-generation antidepressant medications also serve as a useful adjunct in treating myofascial pain, because very often an associated anxiety, depression, or both are present. In addition, numerous welldesigned scientific studies have demonstrated the efficacy of newer-generation antidepressant medication in alleviating neuropathic pain.

Narcotic analgesics generally are avoided unless the pain is refractory. Tramadol may be a useful alternative to traditional narcotic analgesics. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have little role in the treatment of chronic myofascial pain. Muscle relaxants may be quite effective in some patients, especially when abnormal hypercontractility of the involved musculature occurs.

Psychological counseling, group therapy, or both may be an important intervention in patients suffering with myofascial pain, especially those who have been suffering chronically. In such cases, a complex interplay often exists between emotions and pain, or there may simply be a secondary depression that must be addressed. As stated earlier, patients with chronic pain who are also suffering with depression will not improve unless depression is adequately managed.

Therapeutic injections have little role in myofascial pain, other than the judicious use of trigger-point injections. An over-reliance on trigger point injections should be avoided, and such injections should be coupled with manual therapy. Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections have been tried with myofascial pain, but their efficacy is unclear.

Exercise is exceedingly important for patients who suffer with myofascial pain. However, the exercise should be a part of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach, and should be tailored to the patient’s overall clinical presentation. Meditative exercises such as yoga, t’ai chi, and Pilates benefit many patients suffering from myofascial pain. Other forms of exercise, such as walking, swimming, or biking, may be well tolerated and ultimately beneficial, once the pain cycle is under better control.

Surgical

There is little role for surgical treatment in myofascial pain. Too often, patients with myofascial pain undergo surgery for degenerative lumbar discs or similar conditions, only to have increased pain following surgery because surgery does not address the cause of pain. In essence, surgery is yet another trauma that the body must adapt to, and patients with myofascial pain already have a maladaptive response to trauma. Thus, pain can worsen substantially following such surgical intervention.

Spinal cord stimulator placement also should be avoided in myofascial pain, unless patients have an extraordinarily well-localized pain and have exhausted all other aspects of pain management. Even in this case, patient selection must be exceedingly careful. Certain patients, having exhausted all other aspects of pain management, may become dependent on narcotics coupled with a systemic intolerance to these medications. In such cases, placement of a morphine pump may be indicated.

Mind-Body Considerations

A mind-body approach is extremely effective in managing patients with myofascial pain. This is a classic pain syndrome in which a well-defined relationship exists between the emotional response and the pain response.

Many patients who suffer with myofascial pain have undergone physical trauma, but the psychic response to trauma often is underexplored. It is not the traumatic event per se that determines the onset of myofascial pain, but the patient’s interpretation and insight into the traumatic event.

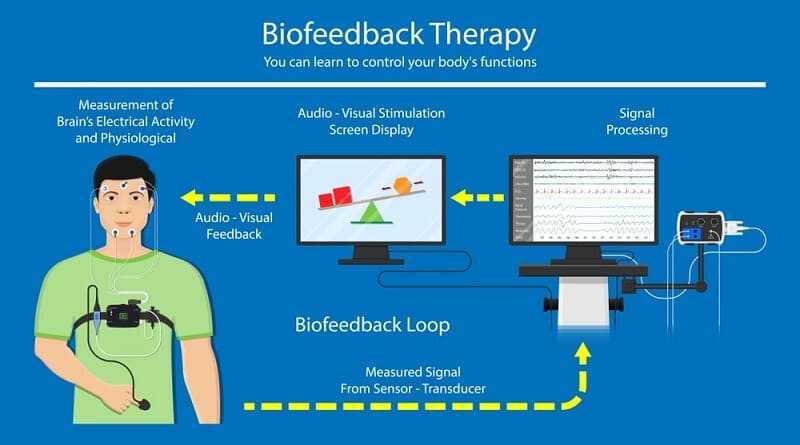

Because myofascial pain can be worsened by emotions and perceptions, meditative techniques, relaxation techniques, and biofeedback help patients to gain insight into the relationship between pain and emotions. At a deeper level of insight, patients with myofascial pain may come to understand a connection between a repressed or disassociated conflict that has no apparent peaceful reconciliation and that has led to a chronic, low-grade, post-traumatic stress-type behavior. Such patients often are exceedingly compulsive and well organized, to the point that every aspect of their day is placed in order. By doing so, patients have developed a sense of order that compensates for the disorder within.

With this latter point in mind, it is interesting to come to an understanding of the patient’s perception of where he was at the time the myofascial pain began. Something such as a minor car accident, in which the physicality of the event becomes the focus of treatment and medical-legal work, may have profound psychic implications. Sometimes the car accident happens when the patient is physically and emotionally at a point of exhaustion. This trauma represents the “final blow,” and the patient begins to decompensate. If pain develops, this may become the focus of the decompensation, because this expression may be psychologically preferable to becoming a witness to the emotional pain. This is not to state that all patients who suffer with myofascial pain have such a simplistic mind-body explanation. However, to resist exploring such a possible connection may limit avenues of appropriate treatment.