Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Lupus, or SLE)

Lupus is Latin for wolf. The name comes from a red rash that spreads in a characteristic butterfly pattern over the bridge of the nose and cheeks of some people with lupus, lending its bearers, it’s said, a wolflike appearance. That’s certainly one explanation for the origin of the name. It was a Parisian dermatologist, Pierre Cazenave, in 1851, who coined the term “lupus erythematosus,” the latter half from the Greek word erythema, meaning redness. Cazenave may have meant to echo the term for skin lesions, known as lupus pernio (pernio is Latin for congestion and swelling of the skin due to cold), that he’d seen in patients with sarcoidosis. A more whimsical notion is that he associated the shape of the rash with a type of mask worn by society ladies at costume balls, popularly called un loup.

Nearly half a century later, Sir William Osler, the great Canadian born physician, realized that many of his patients with the rash had more than a skin condition. The rash was merely a telltale sign of a far more “systemic” ailment—a descriptive modifier he appended to more appropriately describe the overall disease.

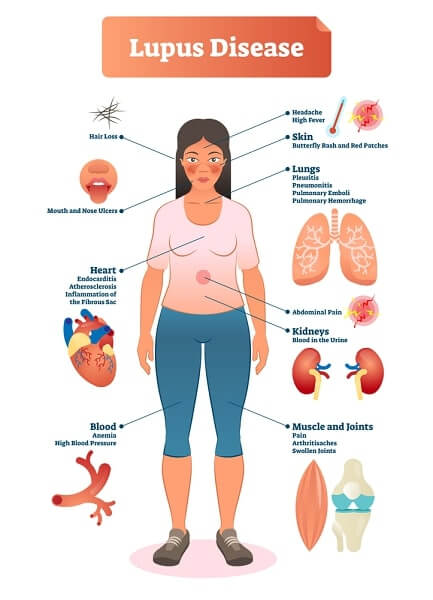

Lupus can and often does cause nausea, weight loss, and muscle weakness, as well as chronic inflammation in many different parts of the body, including the skin, muscles, and joints (the connective tissues), lymph nodes, and spleen. Lupus also poses a risk of kidney damage, in which inflammation impairs the organs’ ability to filter waste products from the blood. The result may be uremia, a poison buildup in the system, which can cause nausea, vomiting, and extreme fatigue, or proteinuria—an excess of protein in the urine, which may in turn lead to edema, swelling in various parts of the body due to fluid accumulation.

Serositis is another potentially severe problem, often taking the form of pleuritis or pericarditis (inflammation of the lining of the lungs or heart, causing chest pain, difficulty breathing, and sometimes fever). In fact, any of the vital organs can be affected. Even the blood vessels of the brain (in rare cases) can become inflamed, leading to paralysis and convulsions.

Many people with lupus also suffer from Raynaud’s phenomenon. As well, among women with lupus who become pregnant, there’s a high incidence of miscarriage, especially in the first three months.

What Are the Symptoms of Lupus?

Lupus is often called “the great pretender,” because many of its symptoms mimic those of other diseases, making diagnosis vexingly difficult, especially during its early stages. A definitive diagnosis can take a year or more. Lupus strikes about one in two thousand people— fourteen to fifteen thousand Canadians—women eight to ten times more often than men. It usually appears in women between the ages of twenty and forty, although it can occur at any age in either gender and is equally common to both after age fifty. In severe cases, it causes death. In fact, as recently as the 1940s, only one patient in six survived three years after diagnosis.

Thanks to intensive clinical and basic science research, that last grim statistic has been radically upgraded, to something like one fatality in ten cases a decade after diagnosis. By far, the majority of people with lupus live full, basically normal lives, as the disease and its symptoms can usually be treated.

People with lupus often suffer from a double affliction. There’s the disease itself, but added to that is an emotionally corroding experience: the misunderstanding and skepticism, sometimes outright disbelief, that many people with lupus are subjected to by colleagues, family members, and friends— even some physicians. It’s partly a visibility problem: How can you be sick, someone will ask, when you look perfectly healthy?

Such queries usually reflect the disease’s own fickle mercies: Sometimes you’re up, sometimes down, victim to an inconstant spectrum of ills. Lupus isn’t a “true” form of arthritis; more accurately, it’s a connective-tissue disease, though it’s classified as a rheumatic disease because its symptoms usually include joint pain and swelling. About half of all people with lupus do develop recognizable arthritis, though very few of them suffer the deformities associated with severe forms of that disease.

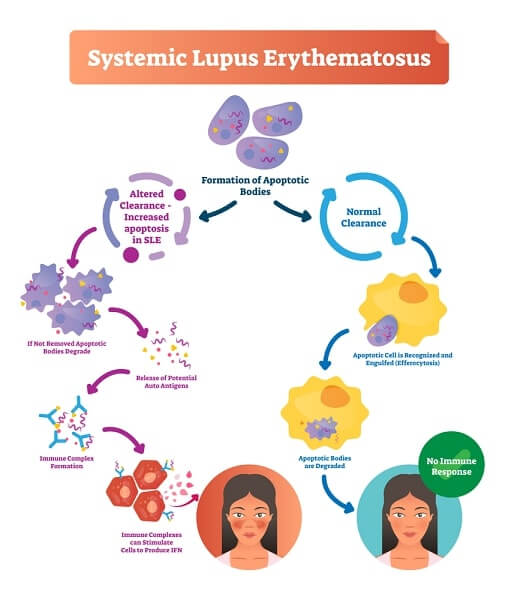

There are still major questions concerning the cause, or causes, of lupus, and a real cure is still only a dream. (It’s known that some people develop drug-induced lupus from taking medications for other conditions.) It is certain, however, that lupus is an autoimmune disease, a disorder in which the body’s own defences turn on itself.

Furthermore, there appears to be an inherited predisposition for the disease, although the specific gene or genes involved have yet to be identified. Current theory suggests that heredity alone can’t explain why some people develop the disease and others don’t. Some external trigger, perhaps a bacterium or virus, may be responsible for starting the disease process in genetically predisposed people. It could also be the result of one or more environmental factors, such as childbirth, hormonal changes, a traumatic injury, an infection—even sunlight.

Diagnosis and Treatment

That unknown trigger is just part of the reason physicians are at such pains to diagnose the condition. Then there’s the fact that no two patients suffer, or present with symptoms, in quite the same way. Symptoms can include anything from hair and weight loss and rashes to ulcerated mouth sores and throat and facial swelling (which may indicate kidney failure). Some people develop mainly joint problems. And any patient can get any combination of the full menu.

Diagnosis begins with a patient’s history. A family history of lupus or another autoimmune disorder, such as rheumatoid arthritis, is a strong clue. The doctor then performs a physical examination to confirm suspicions raised by the history. Joint inflammation, for example, would suggest arthritis, but if there’s a rash that flares from exposure to the sun (see Photosensitivity, below), or other rashes on the body consistent with lupus, the diagnosis is clearer. There are a number of other techniques a physician can perform to confirm the diagnosis, including tests for inflammation around the lungs and heart. There are also lab tests to identify lupus-associated immunological dysfunctions, including tests for FANA (fluorescent antinuclear antibody), anti-DNA, and anti-Sm (a substance found in cell nucleii that was named after a patient—named Smith—in whom the first “anti-Smith” antibody was found).

The difference between Rheumatoid Arthritis and Lupus

The arthritis component is one of the most confusing factors in diagnosing lupus, since many of its symptoms are shared with various rheumatic disorders. As in RA, arthritis in lupus involves synovitis, inflammation of the synovial membrane enclosing a joint capsule, though the intensity of inflammation is less pronounced, and affected joints rarely become disfigured. The range of joints affected is the same, or very nearly so: Any joint in the body is subject to attack, though the most frequent sites in lupus are the wrists, the large knuckles at the base of the fingers, and the middle finger joints.

In the lower body, knees fall victim more often than hips, though hips have their own (admittedly rare) problem—a blood-supply complication called aseptic necrosis (death of tissue without infection). Another major difference between RA and lupus is that, in RA, the inflammatory process leaves bone ends pitted. X-rays of affected joints in lupus almost never show that kind of damage, though the patient may still experience pain, and the joint will be tender to the touch or when if s moved through a range of motion.

Again, only a few lupus patients suffer any joint deformity. When they do, it’s most often in the hands and fingers, and they don’t lose as much dexterity as someone with a comparable degree of RA. Even the process of deformity is different. In RA, disfigurement results from the erosion of bone; in lupus, it’s caused by joint slippage, known as sub- luxation—a partial or incomplete dislocation.

Treatment of Lupus

Today, most cases of lupus are eminently treatable; some people, in fact, require very little treatment at all, depending on their symptoms. Mild forms of the disease can usually be treated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce pain and inflammation. More serious forms of the disease, especially those involving a major organ, call for stronger medications, such as corticosteroids, though the most commonly prescribed medication for moderate to severe lupus is the antimalarial Plaquenil.

Plaquenil has fewer associated side effects than the corticosteroids, though there’s a real risk of serious vision impairment, so frequent checkups with your ophthalmologist (at least every six months) are essential.

Immunosuppressant drugs, such as azathio- prine (Imuran), are reserved for only the most serious cases of lupus, because of their potentially severe side effects.

Rest, diet, and exercise programs all have a role to play in the management of the disease. You may find you tire easily and require scheduled rest periods: Don’t overdo it—fatigue is sometimes enough to excite a flare-up of symptoms. For the same reason, you should investigate relaxation techniques to keep your stress levels to a minimum. Exercise is important to maintain overall body fitness and joint flexibility (and thus reduce fatigue and promote all-round health), but it should only be done in consultation with a physiotherapist or your doctor.

A healthy diet is important to your general health (as it is in any arthritic condition) but, because of the potential complications of lupus, ask your doctor or a nutritionist for specific dietary recommendations—for example, with regard to how much salt or protein you should allow yourself, and what foods will best control the progression of renal (kidney) disease.

Photosensitivity

About one in seven people with lupus suffers from photosensitivity, or reaction to the light of the sun, specifically ultraviolet (UV) light. A certain amount gets through even on cloudy days, and hats and visors are no guarantee of protection. Even fluorescent lights produce UV radiation. While they only emit minute amounts of UVB, the active band of UV light, their effect is cumulative and, over time, they can have the same effect as the sun.

Not every lupus patient has this photosensitivity, says rheumatologist Dr. Carl Laskin, director. Obstetric Medicine Program, University of Toronto, and staff rheumatologist at The Toronto Hospital, “but the thing that’s important about it is, if someone is photosensitive, it’s not just the rash you worry about. You get photoinduction of the immune system, so that the whole disease gets turned on.” People with photosensitive lupus report flare-ups of symptoms after brief periods of exposure, ranging from fatigue and headache to rash, nausea, and joint pain. Some people have even complained of reactions to a half hour’s shopping under the fluorescent lights of a large store.

(Ironically studies have also shown exactly the opposite effect— that exposure to some bands of UV light can actually reduce symptoms in people with photosensitive lupus. Dr. Hugh McGrath, associate professor of medicine at Louisiana State University Medical Centre in New Orleans, reported that exposing patients to low-dose ultraviolet-Al radiation in a controlled setting for ten to fifteen minutes a week eliminated headaches, fatigue, and bad rashes. Not only did patients say they felt much better after brief treatments, those who missed treatments quickly reported feeling worse.)

In general, people with photosensitive lupus are advised to stay indoors during the hottest part of the day, that is, from noon to 3 p.m. If, like mad dogs and Englishmen, you simply must go out in the midday sun, slather on a good sun block, with a minimum SPF (sun protection factor) of 15. Cover arms and legs and sport a broad-brimmed hat, but keep in mind that the sun’s rays reflect up off sand and a variety of hard surfaces, such as metal (in a boat, for example). For a mild rash or skin eruption, a topical cortisone cream may be all that’s required, but a real overdose of sun can cause a reaction requiring emergency hospitalization.