Lumbar Disc Herniation

Clinical Presentation

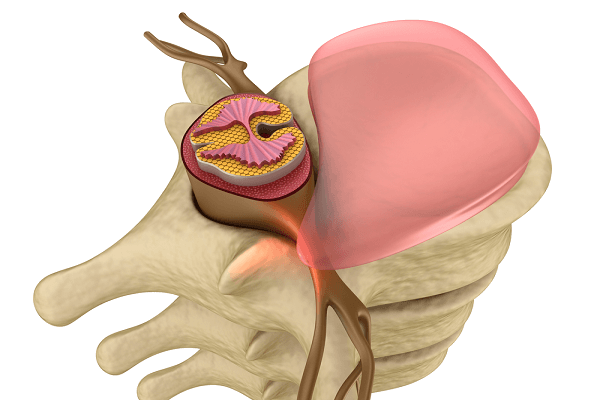

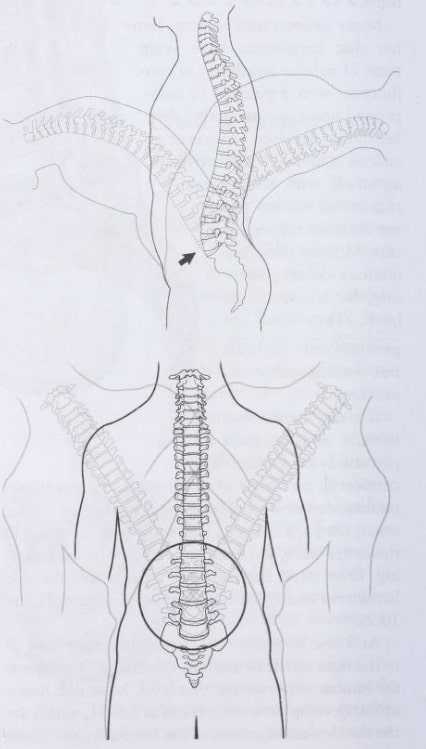

As discussed in this article, the lumbar disc is comprised of an inner gel and an outer annulus. The lumbar discs provide stability and resiliency to the lumbar spine. Lumbar disc herniation develops because of a tear in the annulus of the lumbar spine; the inner nucleus pulposus extends beyond the tear, compromising a part of the spinal canal (Image 1). In many cases, lumbar disc herniation develops insidiously as a result of repeated, small micro tears that develop in conjunction with a degenerative disc. In these cases, patients with lumbar disc herniation may be symptoms. Indeed, modern imaging studies have revealed that lumbar disc herniations may be present in a sizable number of individuals who have no symptoms.

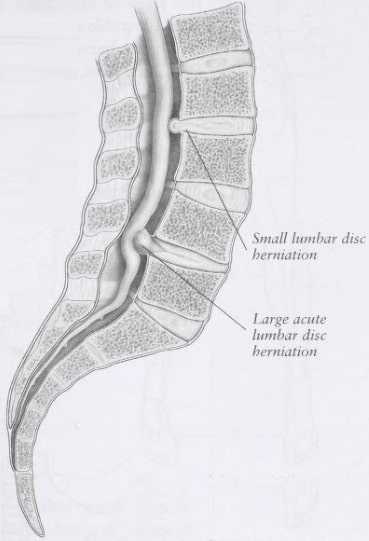

Many patients with an acute lumbar disc herniations have symptoms of pain or numbness in conjunction with a pinched or compressed nerve. Acute lumber disc herniation develops because of a sudden and large tear in the annulus, with subsequent rupture of nucleus pulposus material through the tear. Most of these herniations occur posteriorly, that is, toward the back. They also are generally to one side, but occasionally are midline.

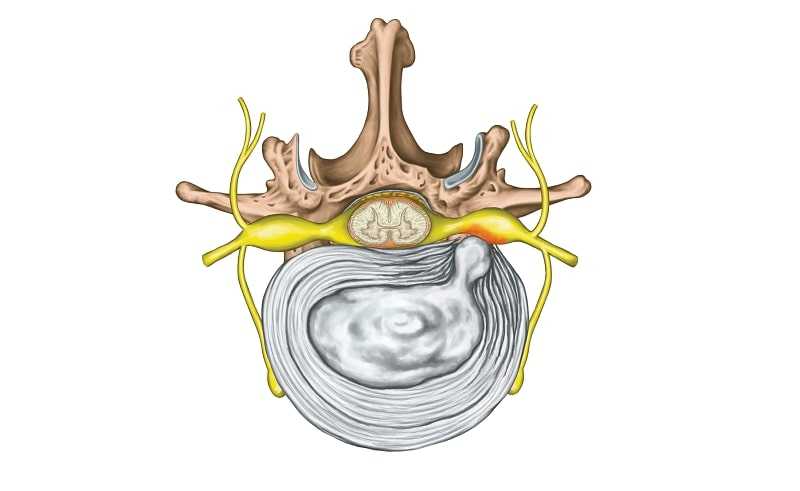

If a disc herniation is initially midline, pain is perceived as a deep discomfort in the center of the lower back. Sometimes patients describe a sudden popping sensation. Other times, the patient senses that something is wrong in the lower back, but the pain may not be excruciating. Over days, the tear may enlarge and the disc herniation worsens while symptoms increase (Image 2).

As a disc herniation enlarges, it generally does so to the right or left of midline. Often, it will compress the lumbar nerve root at that level. Most disc herniations develop between L4-L5, or L5-S1, which are the two lowest segments of the lumbar spine. These two levels of the lumbar spine are the most mobile and vulnerable segments (Image 3). When a nerve root is compressed, there may be associated pain, and pain will normally be Perceived in the sensory distribution of that nerve. For example, a herniated disc at L4-5 may compress either the right or left L5 nerve root, which may cause pain radiating down the right or left side of the leg and into the great toe. If the nerve is severely compressed, there may be numbness (corresponding to the same sensory distribution) or muscle weakness. This demands urgent neurological evaluation.

Patients with acute lumbar disc herniation typically are comfortable lying on their back with knees flexed. Sitting is often uncomfortable, and standing may or may not be comfortable. Patients generally avoid bending forward, and sudden coughing or sneezing can worsen symptoms.

Cause of Lumbar Disc Herniation

The cause of acute lumbar disc herniation is not always apparent. Patients with chronic, degenerative lumbar discs and associated disc herniations often have a genetic predisposition to such degenerative changes. Otherwise, lumbar disc herniations generally occur in the setting of repeated overuse of the lumbar spine or sudden, more severe overuse. In this case, it is not simply the supporting musculature that gives, but the stabilizing force of the lumbar spine itself.

For degenerative lumbar disc herniations, the inner contents of the nucleus pulposus undergo a gradual change, which leads to a loss of water content in the nucleus pulposus. This drier disc makes the annulus susceptible to repeated micro tears. For an acute annular disc tear, the inner nucleus pulposus is generally healthy, and the water content is normal or near normal. The ultimate clinical expression of a lumbar disc herniation depends on the size and location of the disc. Large, midline central disc herniations cause primarily low back pain and, if they are severe, may lead to a worrisome neurologic presentation (discussed next). Discs that lateralize to one side or the other generally are associated with radiating leg symptoms, appropriate to the nerve root that is compromised.

Physical Examination

Patients with acute lumbar disc herniation are generally in considerable pain. They may be tilted to one side or the other, especially if the nerve root is compromised. Forward bending generally is quite uncomfortable. From a seated position, a straight leg-raising maneuver, as demonstrated in Image 4, may reproduce the patient’s pain by stretching the compressed nerve. Areas of palpable muscle spasm may be present in the lower back. Even if a nerve root is compromised, the neurologic exam may be normal. If nerve compression is severe enough, then there may be a loss of sensation, a loss of reflex, or motor weakness that corresponds to the level of nerve dysfunction.

Imaging and Diagnostic Studies

Although plain radiographs are often obtained in the work-up of patients with lumbar disc herniation, they are generally unhelpful. The usefulness of a plain radiograph is more for excluding other causes of back and radiating leg pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the diagnostic study of choice for lumbar disc herniation. If the clinician suspects a large disc herniation, or if any neurologic compromise is present, MRI should be obtained immediately. Otherwise, for a more typical presentation of lumbar disc herniation that is not improving with nonsurgical treatment over a period of a few weeks, then an MRI should be obtained.

In chronic disc herniations, MRI will show loss of water content in a disc, but no evidence of an acute tear of the annulus. In acute disc herniation, on the other hand, the water content of the disc appears more normal. The relative water content of the disc can be determined with certain MRI sequences in which the water signal appears white.

Too often, radiologists interpret MRI studies without differentiating acute from longstanding changes in a lumbar disc. Thus, from the report alone, the physician does not know if the disc herniation developed recently or is longstanding. If MRI studies cannot be obtained, then a computed tomography (CT) scan is acceptable, although this provides less information about the disc itself.

Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies should be obtained if worrisome neurologic compromise is present. This helps to sort out the degree of nerve damage. For more straightforward cases of lumbar disc herniation that do not involve numbness or weakness of the leg, EMG and nerve conduction studies are generally not necessary.

Treatment Considerations

Nonsurgical

Most patients with acute lumbar disc herniation can be treated nonsurgi-cally. This is because the disc, over time, will gradually recede, thereby relieving pressure on other spinal elements. Even if a disc recedes completely, a disc that is herniated will never again be normal. Some water content will be lost, and subsequent degenerative changes may occur, leading to some loss of normal lumbar spine stability. Thus, long-term treatment must be directed at helping to restore spinal stability by other means.

Medications usually are indicated in the acute treatment of lumbar disc herniations. Antiinflammatory drugs are quite useful in helping to alleviate inflammation and pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be prescribed for 1 to 2 weeks. If pain is more severe, a corticosteroid may be prescribed for a 5- to 10-day course, instead of other anti-inflammatory drugs. Other medications include muscle relaxants if associated muscle spasm is present, or judicious use of narcotic analgesics for more severe pain.

Patients with acute lumbar disc herniation are generally too uncomfortable to undergo traditional physical therapy, although they may benefit from myofascial release or similar techniques. Acupuncture may be helpful, although the success of acupuncture for radiating leg pain is less than it is for low back pain per se. Spinal manipulation should not be utilized as an initial treatment for a lumbar disc herniation. Gentler mobilization techniques are appropriate. Epidural injections should be utilized if pain persists despite medication management and hands-on treatment. If pain is primarily in the leg as a result of a single nerve compression, then a selective nerve root injection is appropriate.

Once patients obtain reasonable pain relief, physical therapy should begin. Too often, patients arrive in a physical therapy facility, which is really no more than a mill, and they receive a “make, shake, and bake” approach in which multiple patients are treated simultaneously with a combination of modalities and cookbook-type exercises. More successful physical therapy employs a combination of manual techniques that help to restore muscle balance while allowing the therapist to understand relative areas of muscle weakness and imbalance. From there, a progressive spine stabilization protocol should begin. Over the long term, spine stabilization is the preferred treatment for patients who have suffered with lumbar disc herniation.

In conjunction with physical therapy, patients should be encouraged to resume or to return to exercise. If spine stabilization is successful, patients generally can return to any type of exercise.

Surgical

There are two absolute indications exists for immediate surgery in patients who present with a lumbar disc herniation:

- Bowel incontinence, bladder incontinence, or both that is attributable to the disc herniation.

- Progressive motor weakness or absolute motor weakness, attributable to the disc herniation.

If a disc herniation is quite large and primarily central, considerable compromise of the spinal canal can occur. This can then lead to a compression of the nerve roots that control the bladder and rectal region. If compression of these nerve roots is sufficient, patients become incontinent because the nerves are damaged (Image 5). This is a neurologic emergency: Patients should be evaluated immediately by a spinal surgeon to undergo immediate spinal decompressive surgery.

Similarly, patients with rapidly progressive or absolute motor loss are at risk of permanent motor loss and should be evaluated immediately by a spine surgeon. Delay in surgical treatment for either scenario may result in permanent incontinence, muscle weakness, or both.

The third surgical indication is relative. For patients who have undergone good nonsurgical management, but who have refractory pain that is appropriate to the level of disc herniation, then surgery is indicated. The timing of surgery is a decision to be made between the patient and surgeon. Generally speaking, ongoing leg pain from an acute disc herniation should not persist beyond 3 months and, if nonsurgical therapy has failed to yield positive results by this time, then surgery is an appropriate option.

The medical risks of surgery must be considered carefully (see this article). As noted, the medical and rehabilitation risks of surgery are more substantial for patients undergoing spinal fusion when compared with patients undergoing laminectomy or discectomy.

For a single-level disc herniation, surgery generally can be accomplished by way of a laminectomy or laminotomy with microdiscectomy. The herniated disc fragment is removed. Surgery is not curative for the remainder of the disc, and this disc will undergo some degenerative changes regardless of whether surgery has been performed. Successful surgery for a single-level disc herniation should lead to immediate cessation of pain. If pain relief is not immediate despite appropriate disc fragment removal, then possible physiologic causes of pain should be addressed.

Patients generally recover from surgery immediately and are discharged within 1 to 2 days. They often are walking the day of surgery, and resume full activity within weeks. As with patients who have undergone nonsur-gical treatment, patients who undergo surgical treatment should ultimately work with a physical therapist who specializes in spine stabilization. These patients will benefit from a detailed analysis assessing muscle balance and strength, and should undergo a progressive spine stabilization protocol.

Unless other complications are present within the spine, such as multilevel degenerative changes or spondylolisthesis (discussed in this article), patients do not require spinal fusion. Some physicians utilize laser surgery, which essentially shrinks the disc and accelerates degenerative changes. The long-term success of laser surgery has not been well studied.

Mind-Body Considerations

More often than not, patients and their treating clinicians focus on an inciting physical event that led to a disc herniation. Although this may provide part of an answer as to why the patient developed a disc herniation, the intent or perception surrounding the inciting event also may provide important clues. Psychological stress can lead to considerable physiologic changes in the body, including abnormal contraction of the lumbar spine musculature and even an abnormal spinal posture.

It is helpful for the patient to understand his perceptions around the time that pain developed. To do so requires either considerable trust between the patient and clinician, or the patient must be engaged in some type of mindful or meditative activity. Mindful and meditative activities allow individuals to move away from the distractions of day-today life and move into a place of turning inward, which may lead to a possibility of insight regarding various signals from the body.

Too often, we are unaware of day-to-day stressors. Then, when we become suddenly ill or injured, the focus turns to the injury or illness and not to our own sense of well-being versus our own sense of distress. This is not to say that all patients who develop a lumbar disc herniation have experienced stress. Rather, providing an opportunity for mindfulness may sometimes yield considerable beneficial results.