What is Charcot Marie Tooth disease

During my time as a specialist practicing General Internal Medicine, with a focus on Pain Management, I encountered many unusual causes of chronic pain. In most cases, the patients were referred to me for management of their chronic pain and had already been diagnosed by various sub-specialists.

One of the most challenging syndromes I faced in clinical practice was an inherited condition called Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease (CMT). All my cases of CMT came to me already with a diagnosis and ample medical records. I came to realize that Charcot-Marie-Tooth was a very painful disorder…indeed (see the picture. It is a person with advanced CMT).

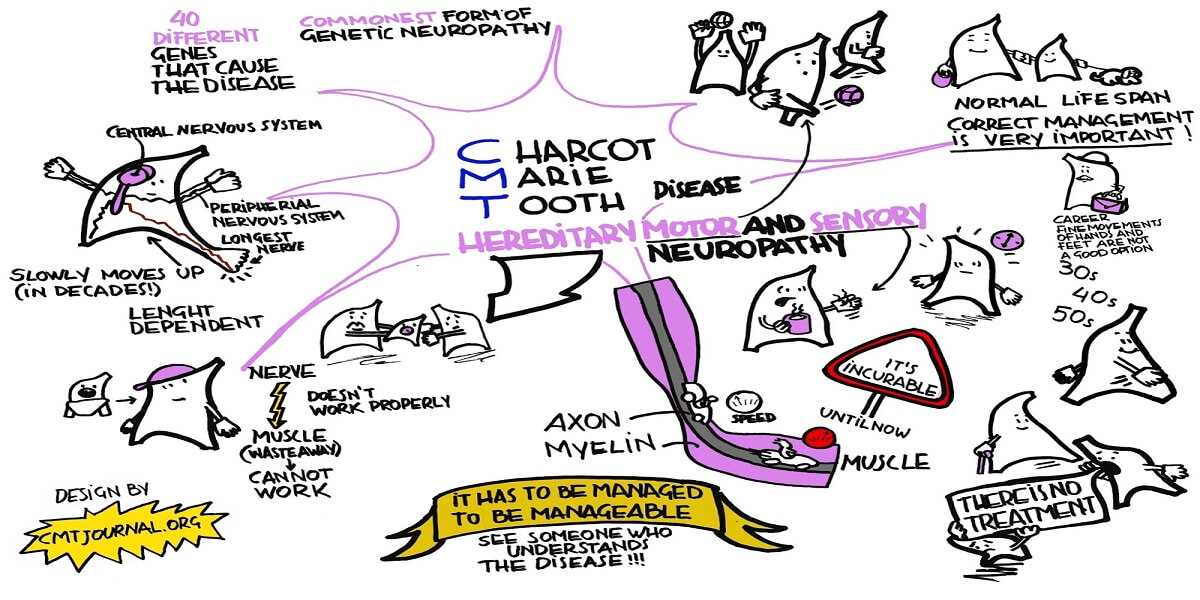

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is a neurological disorder named after the three physicians who first described it in 1886 — Jean-Martin Charcot of France, Pierre Marie of France, and Howard Henry Tooth of the United Kingdom.

CMT is the most commonly inherited peripheral nerve disorder affecting about 1 in 2,500 people.It affects more than 250,000 Americans. Since this condition is frequently undiagnosed, misdiagnosed or diagnosed very late in life, the true number of affected persons may actually be higher.

A Real Case of Charcot-Marie-Tooth

Tracey (her name has been changed) came to my office on referral from a friend. She was siting patiently in the exam room with a “quad cane” at her side when I first entered the examination room. “Hello Tracey, I see you have brought a very extensive copy of your medical records with you. The records indicate that you have been diagnosed with Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease. How may I help you?” I said somewhat uncertain of just what her condition was.

“Yes, I have been to a number of Doctors for my condition. None of them seemed to know what I have. It took 7 years and 7 different Doctors before anyone could figure out my case,” she said with a frustrated tone of voice. “Do you know what it is, Dr. Bado?”

It was never my style to pretend to know something when I didn’t…”Tracey, to be honest with you, I remember the name from medical school but I have never had a case with this disease. But, if you will work with me, I will research what you have and on your next visit I will be fully acquainted with it,” I said a little embarrassed at my ignorance.

Tracey smiled, “You are the first Doctor I met who admitted that they didn’t know what it was. I think you and I are going to do just fine.” I was relieved that I had not disappointed her.

“Tracey, why don’t you tell me just how you feel and maybe I can begin some therapy today?” My goal with every new patient in my practice was to establish trust as early as possible. I believe the best way to do that is to let a new patient tell their story without any time pressure or interruptions. Here is what she told me over the next hour…

Tracey had been in good health until she was in her mid-30s when she noticed she began to stumble without warning. This happened even when she was walking on flat surfaces that most people would not stumble on. It had led to her falling occasionally. She had embarrassed herself at several social gatherings with friends because of this. Her husband had even accused her of drinking too much alcohol at a party where she had fallen…he was embarrassed too.

She went to her Family Doctor who could not find anything wrong with her. Her husband was becoming skeptical and did not want to go to social functions with her. This put an additional strain on their already fragile marriage.

Over time her condition worsened. After a year she began to notice her feet were “numb” to the touch but felt as if they were always burning. There were no visible changes to her feet though. She had always had “high arched” feet but was able to walk just fine. She found she was unable to wear high heeled shoes anymore as her ankles would “give out.” She went to another Family Doctor who spent 10 minutes with her and told her she was “just clumsy.”

On several occasions she went to the Emergency Room of her local community hospital when the burning of her feet became unbearable. The Doctor spent 2 minutes with her, ran a few blood tests looking for “arthritis”, and gave her some Motrin. It didn’t help…she was getting worried.

Her social life was becoming unmanageable as she began to isolate herself due to her frequent stumbling and falls. Furthermore, she was unable to stand for long periods at work (she worked on an assembly line) and had to quit. Her husband was sure she was just malingering since none of the Doctors could identify what was wrong with her and she no longer wanted to be physically intimate with him.

By the time she was in her early forties she had pain in her feet all the time, had difficulty just walking around her home, and had fallen down the stairs from the second floor several times. The Family Doctor she was seeing referred her to a Neurologist. In one visit he diagnosed her with CMT and told her the bad news…she had an incurable disease that will only get worse. He offered her little in the way of pain relief. He told her she would just have to “live with the pain.” She considered suicide…only the recent birth of her grand-daughter kept her from attempting to end her life.

Tracey’s story with CMT is not unusual. Neuropathic conditions often have little in the way of observable abnormalities. This makes it difficult for an untrained person to be able to relate to a person suffering from CMT. In fact, even Doctors are often fooled by the lack of physical findings.

Let’s discuss for a moment just what is happening to the human body with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

Anatomy and Physiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth

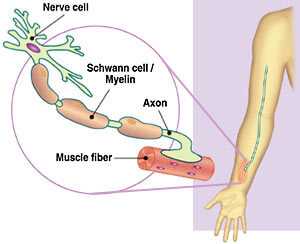

In the normal human body nerves are attached to muscles where the muscle is then “given instructions” for movement from the nerve. Nerves that are required to transmit signals rapidly are covered with a form of “insulation” called myelin. This allows the electrical signal to travel rapidly along the tail of the nerve called an axon.

If the myelin or the axon itself is in anyway disrupted, the transmission of the nerve signal is affected. If the nerve signal is affected the muscle that is relying on the signal for instructions will not function properly. Walking is a very complicated function and requires precise coordination of the muscles of the legs and feet to occur.

Furthermore, the information from the bottom of the foot is sent up to the spinal cord and brain for precise adjustment during walking. Simple numbness of the bottom of the foot can make walking difficult. Numbness often preceeds weakness in people with CMT disease and may not be noticed by the person suffering from the disease in the early stages.

CMT can affect the myelin, the axon proper, or both. The more disruption of the myelin and axon…the more dysfunction that occurs. The process is on-going in people with CMT and is not visible in the early stages.

In CMT there is a genetic alteration that renders the myelin dysfunctional and/or the mitchondria inside the axon defective (mitochondria manufacture energy). These 2 processes can result in what is called a neuropathy.

Diagnosis of CMT

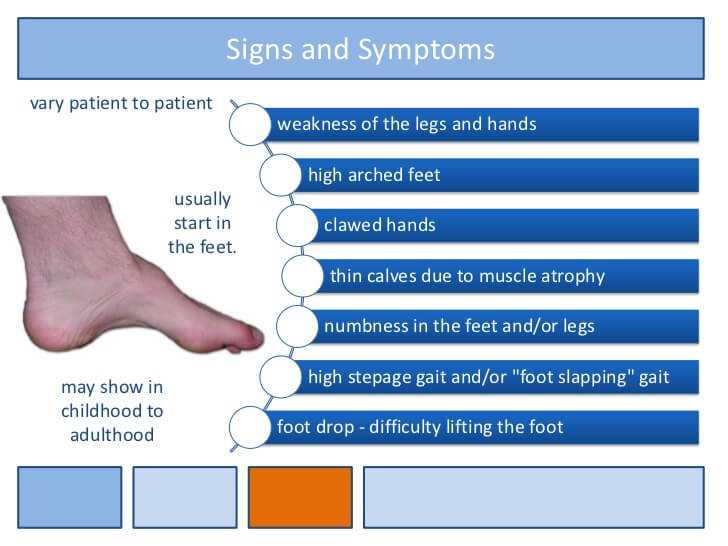

The diagnosis of CMT is suspected when the following history, symptoms, physical signs, and diagnostic findings are manifested by a patient:

HISTORY

People with CMT will often relate a history of difficulty walking, running, unprovoked falling, leg weakness or numbness, hand weakness or numbness, and loss of fine motor movement of the fingers.

There may be a family history of similar symptoms (or perhaps even a diagnosis). It is not unusual for people to have a long delay in diagnosis if their examining Doctor has never seen a case.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

1)Decreased sensitivity to heat, touch, or pain of the feet and/or hands.

2)Muscle weakness of the feet, lower legs, or hands.

3)Trouble with fine motor skills of the hands.

4)Foot drop

5)Loss of muscle mass of the lower legs.

6)Unprovoked tripping or falling.

7)Hammertoes

8)High Arched Feet

9)Flat Feet

10)Loss of Patellar and Achilles reflexes.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

- Needle Nerve Conduction/Electromyogram

The classic diagnostic study for CMT is a nerve conduction/electromyogram study (NC/EMG). This is performed by inserting needles into nerves and muscles and placing a small electrical charge through the needles to stimulate a nerve or muscle. The response of the nerve or muscle is graphically recorded and interpreted by a physician.

The NC/EMG is an uncomfortable study. Imagine having needles inserted into areas that already are painful. Few patients will subject themselves to more than one study after having experienced the discomfort of the first.

The graphic findings are diagnostic for nerve or muscle dysfunction. The study is limited by the discomfort it causes, the precision of the needle insertion, and can only detect larger nerve fiber dysfunction. Small nerve fiber abnormalities can be missed with this type of diagnostic study.

- Neural Scanning

There is a fairly recent improvement in the detection of nerve dysfunction called Neural Scanning (NS). NS does not require needle punctures…the electrical current is applied via skin pad electrodes. The particular electrical frequency of stimulation used allows for the measurement of both large and small fiber nerves (remember needle NC/EMG can only measure large nerve fibers).

In this way, early detection of neuropathic changes in very small nerve fibers (called C fibers) can be detected with Neural Scanning. Furthermore, it is a painless way to stimulate nerve fibers. I prefer this method of nerve and muscle stimulation as the patients tolerated it much better. They were more likely to allow me to recheck their results after they had been on therapy. Most of my patients viewed the needle NC/EMG as torturous but readily accepted multiple Neural Scans.

The following diagnostic studies are also performed at the discretion of the examining physician:

- Nerve Biopsy: this looks at the health of the nerve microscopically. Obviously, the patient requires a minor surgical procedure for this…possibly causing more pain.

- MRI imaging: usually of the feet and lower legs. This may show atrophy in a pattern consistent with demyelination or axonal injury.

- X-Rays of the feet and/or hands: prolonged and severe neuropathy can actually result in resorption of the toes and fingers. By the time this test is positive the disease is usually quite advanced.

The definitive way to specifically diagnose CMT is with genetic testing. Molecular genetic testing is currently available for CMT1A, CMT1B, CMT1D, CMT2E, CMT4A, CMT4E, CMT4F and CMTX. The following section is an in depth review of the present combinations of genetic abnormalities found in CMT.

GENETIC SUBTYPES

Today, CMT is precisely diagnosed by genetic testing. There are many sub-types as assigned by the specific genetic defect. Each sub-type is classified according to the specific genetic defect, where the main disorder resides (whether of the nerve axon or of the myelin sheath around the axon), age of onset, severity of dysfunction, and body parts affected. The most recent classification is as follows:

- CMT1A: A subtype of CMT1, called CMT1A (caused by a duplication in the PMP22 gene on chromosome 17) accounts for around 60 percent of CMT1 cases, making it the most common subtype of CMT1. The PMP22 gene encodes for peripheral myelin protein, and disruption of this gene leads to a dysfunctional myelin sheath on nerves. CMT1A patients usually present with typical CMT onset within adolescence, but remain ambulatory with no reduced life expectancy.

- CMT1B: CMT1B is the second most common subtype of CMT1. CMT1B is caused by a defect within the MPZgene, which lies on chromosome 1. The MPZ gene produces myelin protein zero, and disruption of this gene also causes deficits within the myelin sheath. CMT1B patients have onset and symptoms similar to those of CMT1A patients, although there is a wide range of variability within CMT1B.

- CMT1C: caused by defects in the LITAF gene.

- CMT1D: caused by defects in the ERG2 gene.

- CMT1E: caused by defects in the PMP22 gene, which is also associated with CMT1A. Instead of having a duplication of the normal PMP22 gene, CMT1E patients harbor different genetic abnormalities called point mutations within the PMP22 gene.

- CMT1F: caused by defects in the NEFL gene.

- CMTX: caused by mutations in the gene for connexin 32, which normally codes for a protein located in myelin, the insulating sheath that surrounds nerve fibers. Because this form of CMT is X-linked, it affects males more frequently than females (all other forms of CMT affect males and females equally).

- CMT Type 2: (CMT2) is a subtype of CMT that is similar to CMT1 but is less common. CMT2 is typically autosomal dominant, but in some cases can be recessive. CMT2 is caused by direct damage to the nerve axon itself in comparison to CMT1 which results from damage to the myelin sheath insulating the axon. CMT2 is commonly referred to as “axonal” CMT. CMT2A is the most common subtype of CMT2 and is caused by defects in the MFN2 gene. The MFN2 gene encodes for Mitofusin 2, which is a protein involved in the fusion of cellular mitochondria.

Other more rare forms of CMT and their gene defects include:

- CMT2B: caused by defects in the RAB7 gene.

- CMT2C: caused by defects in the TRPV4 gene.

- CMT2D: caused by defects in the GARS gene.

- CMT2E: caused by defects in the NEFL gene.

- CMT2H: caused by defects in the HSP27 gene.

- CMT2I: caused by defects in the HSP22 gene.

- CMT3: severe, early onset CMT is a sub-type of CMT that is a particularly severe variant of the disease. Other terms used to describe this variant include Dejerine-Sottas disease, and congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy. Severe, early-onset CMT can be inherited in either an autosomal dominant or recessive pattern.

CMT3 is a severe neuropathy with generalized weakness sometimes progressing to profound disability, loss of or changes in sensation, curvature of the spine and sometimes mild hearing loss. Severe, early-onset CMT begins in infancy or early childhood, and progresses slowly. Severe disability may eventually occur.

CMT3 is caused by defects in the genes for proteins found in axons or in the genes for proteins found in myelin. Some of these same genes also cause CMT1 and CMT2 such as PMP22, MPZ, and GJB.

- CMT4: a rare subtype of CMT, a genetic, neurological disorder that causes damage to the peripheral nerves — tracts of nerve cell fibers that connect the brain and spinal cord to muscles and sensory organs. CMT4 is a subtype of CMT that is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. CMT4 is caused by defects in the myelin sheath which insulates the axon. Symptoms are generally more severe than in CMT types 1 or 2.

There are sub-types for this severe type of CMT also:

- CMT4A: caused by defects in the GDAP1 gene.

- CMT4B: caused by defects in the genes MTMR2 (CMT4B1), or MTMR13 (CMT4B2).

- CMT4C: caused by defects in the SH3TC2 gene.

- CMT4D: caused by defects in the NDRG1 gene.

- CMT4E: caused by defects in the EGR2 gene.

- CMT4F: caused by defects in the PRX gene.

- CMT4H: caused by defects in the FDG4 gene.

- CMT4J: caused by defects in the FIG4 gene.

Treatment of CMT

As CMT is presently incurable, treatment is aimed at reducing pain, limiting orthopedic complications, improving functionality, treating depression, and adjusting to the emotional/social isolation that can occur with this devastating illness.

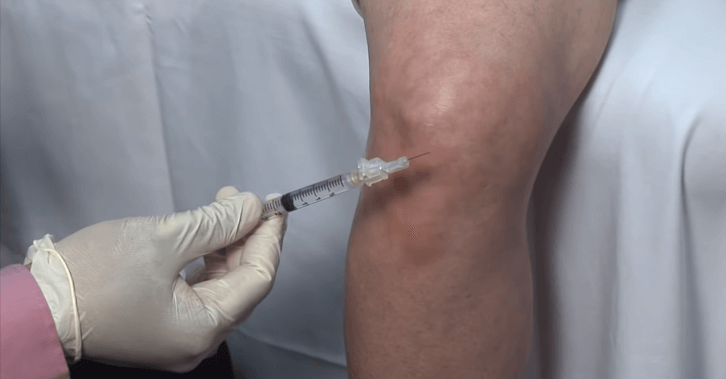

I recommend my article on, “The 7 Best Treatments for Chronic Pain” as a starting point for therapy of CMT (click here to link to that article). In addition to the therapies recommended in that article, the following are usually listed as therapies for CMT:

- Physical Therapy

- Shoe Orthotics (shoe inserts)

- Leg Bracing

- Selective Orthopedic Surgery (for limb deformity)

Effective treatment of pain is essential with CMT. Simply instructing a patient that they must “live with it” is an insufficient response of a Doctor to a patient in chronic pain. Chronic pain causes negative physiologic changes to the immune system, nervous system, cardiovascular system, endocrine system, cerebrovascular system, and nearly every other system of the human body.

All cause mortality is also increased in people with under-treated chronic pain. This means that existing disorders are often made worse in the presence of chronic pain. The effect of chronic pain on existing disorders is often under-reported since the cause of death is never “Untreated Pain” but usually reflects the underlying disease process.

There is hope…

Are you wondering what happened to “Tracey” (the case history I presented at the beginning of this long article)? Her outcome was one of the many successes in my Pain Management practice.

On the first long visit with Tracey I was able to establish that her pain was averaging an 8 or 9 out of 10 when not treated. My custom for my pain practice was to query a new patient as to what medicine in their past history worked best for their pain. Thereafter, I would estimate the dose based on their usage history.

In Tracey’s case I took a pragmatic approach:

FIRST…I prescribed a short acting opiate pain medication to be taken every 4 hours while awake. This would mean that her starting dose would require 240 pills for the month (1 every 4 hours and 2 at bedtime so she could sleep 4 or more hours). The “start low and go slow” mantra that seems to have infiltrated the medical literature didn’t make sense to me in a patient who was already opiate tolerant.

Nowhere else in medicine do we “start low and go slow” with a patient who already has historically demonstrated an effective dose. Can you imagine a patient with severe high blood pressure, who has been maintained on effective doses of medication, seeing a new Doctor and restarting their medications at the lowest dose possible? They could have a complication doing this (such as a stroke).

Why is this done with opiate pain medications? It is done this way because the fear of inducing addiction (and potential legal reprisal) is more important to most present day physicians than effectively treating a patient’s pain. The actual risk of addiction in a chronic pain patient (with whom there is no history of addiction) is less than 1%. The opiate “naysayers” seem to ignore this statistic in favor of political correctness.

Once I had established what Tracey would need to keep her pain at a “5” with the short acting opiate, I then converted her to a combination of long acting opiate pain medicine as “background” coverage for her pain and short acting opiate pain medicine for “break-through” pain (the episodes where her pain intensified during the day). This usually takes several sequential visits. Most of my patients had their pain effectively treated within 6 months or less.

The format of using a combination of long acting opiate pain medication with short acting for “break-through” pain mirrors the way in which diabetics are treated with insulin. In a diabetic, a long acting insulin is given as “back-ground” coverage of their blood sugar. Then, before each meal. a fingerstick blood sugar is checked and a “sliding scale” dose of short acting insulin is given to “cover” any spike in blood sugar. The dose of the insulin is never arbitrarily limited but is determined by how high the blood sugar is. So it should be with the dosing of opiate pain medications.

SECOND…I considered starting Tracey on a slower to act medication that reduces pain conduction (such as Lyrica). It may take weeks to work so having the opiate pain medication gave immediate relief and hope. The adjustment of the Lyrica dosing will take months due to each new dose requiring weeks of observation to see if it was reducing her pain.

THIRD…I also considered giving Tracey an anti-depressant that recycles both norepinephrine and serotonin (such as Cymbalta). This type of medicine has shown great promise in reducing pain and alleviating depression (of which most chronic pain patients suffer).

All of these medicines are prescribed with the consideration of potential side effects, drug interactions, previous tolerances, and whether the patient’s insurance will cover the cost of the medicines (a HUGE consideration when considering what medicines to choose).

Within 8 weeks I was able to lower Tracy’s chronic pain level to a “5” where she remained until I retired in January of 2013. She had been a patient of mine for over 7 years at the time I retired and her pain was well controlled throughout the entire period of time. Don’t believe the misinformation that “long term” opiate therapy doesn’t work. Just ask “Tracey”…

If you are suffering with CMT (or any chronic pain syndrome for that matter) there is hope for you. You will need to find a physician who is willing to prescribe the medications you need. They are out there…don’t give up looking for them.

I hope you have enjoyed this rather long article on CMT. It has been my privilege to share this information with you. If you have further questions or comments, please send below it. I will promptly respond.

Wishing you joy and healing,

Facebook

Google+

Twitter

Pinterest

Reddit

StumbleUpon

Skype