YOUNG-ONSET PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Since popular actor Michael J. Fox announced that he has Parkinson’s disease, the public and the medical community have become increasingly aware that younger people are not immune to this illness, and that even people in their thirties can be at risk. Fox’s courage and advocacy in speaking out has forever dispelled the Parkinson’s stereotype of the elderly person with a stooped posture, tremor, and slowed gait.

Michael J. Fox

How common is Parkinson’s disease in young people? Most Parkinson’s disease specialists use the term young-onset Parkinsons disease (YOPD) when a patient develops symptoms before age 40. Approximately 5 to 10 percent of all persons with Parkinson’s disease in North America and Europe have an onset before age 40. A very small percentage of YOPD patients are juvenile-onset Parkinson’s disease or JP (juvenile Parkinson’s), and develop symptoms before 21.

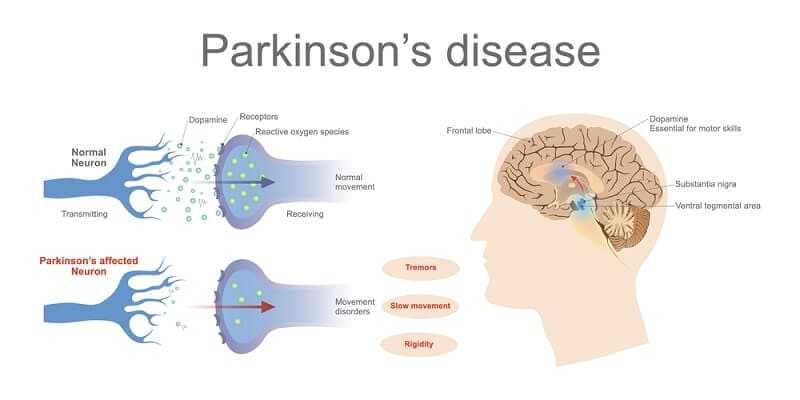

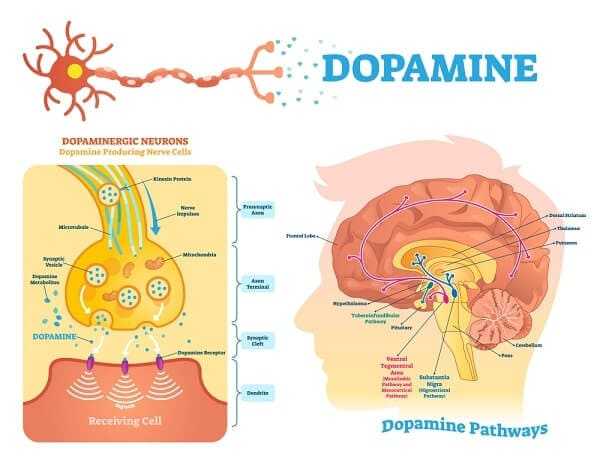

Pathologically, YOPD and adult-onset Parkinson’s disease are the same, with the classic loss of dopamine neurons in the SNc (Substantia nigra compacta) and the presence of Lewy bodies. But YOPD differs from adult-onset Parkinson’s disease in several ways. Younger patients tend to respond better to dopamine-stimulating drugs, and motor symptoms are more easily controlled. YOPD patients may also develop motor fluctuations such as “wearing off,” “on-off,” and dyskinesia earlier than adult-onset Parkinson’s disease patients, sometimes within months or a year of starting levodopa therapy. It has been estimated that up to 55 percent of YOPD patients will develop dyskinesia within one year of starting levodopa, and 74 percent by the third year. This is much higher than the adult-onset rate of 28 to 50 percent experiencing dyskinesia and motor fluctuations 3 to 5 years after starting levodopa. Limb dystonia (sustained cramping and posturing of muscles) occurs early on in the course of Parkinson’s disease in up to 43 percent of YOPD patients, compared to only 4 percent of adult-onset patients. Cognitive changes and difficulty with memory are far less common in YOPD. Young-onset patients do have motor symptoms of tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia similar to older-onset Parkinson’s disease patients but have less gait difficulty. It is generally agreed that YOPD progresses at a slower rate than adult-onset Parkinson’s disease.

Getting Diagnosed

Getting an initial diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease may be difficult for younger people— and it may even be delayed by many years—because some physicians aren’t experienced in diagnosing YOPD.

Sam’s story reflects this problem. Sam began noticing something was different around age 30.

I felt shaky on the inside of my body and had difficulty holding my razor to shave. My hands felt stiff and achy. My family doctor prescribed an anti-inflammatory medication for arthritis. It didn’t work and my symptoms got worse. A year later, after all the blood tests and X-ray reports failed to prove I had arthritis, I was referred to a neurologist, who diagnosed me with carpal tunnel syndrome. I wore wrist splints and took prescribed pain pills, but it didn’t help. I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t know what it was and neither did the doctors. Finally, I began to have bad tremors in both my hands and was referred to a different neurologist, who specialized in Parkinson’s disease. She told me straight out that she thought I had Parkinson’s disease. Even though I was only 33 years old, I was actually relieved to finally know what I had and to know that there was treatment available.

One patient, Joanne, had symptoms that started at the young age of 18, when she had trouble holding a pen at college.

My body was stiff and sore and it was hard to get out of bed in the morning. My walking slowed down. I looked and felt like my grandmother. The doctors were baffled. My parents took me to so many different medical centers and I had so many blood tests and brain and body scans and even had to see several psychiatrists. Some of the doctors thought I was just depressed, and having difficulty adjusting to college life. I was depressed, all right— depressed that no one but my parents believed me and no one could figure it out! Finally, after five years of searching, we found an expert doctor in Parkinsons disease and he knew right away that I had it. I was started on Sinemet and it was like a miracle, my body was free again to move. . . . The most important thing I can recommend to a young person with Parkinson’s disease is to find a doctor who specializes in Parkinson’s disease. It makes such a difference.

Treatments

YOPD should be treated differently than adult-onset Parkinson’s disease, particularly with regard to medications. Because of the greater risk of developing motor fluctuations (“wearing off,” “on-off,” and dyskinesia) with levodopa in YOPD, levodopa therapy should be delayed for as long as possible, and dopamine agonists, amantadine, and anticholinergics considered for the treatment of disabling motor symptoms. Many patients will need to add levodopa within three to five years of beginning medication therapy to adequately control the tremors, bradykinesia, and rigidity. The goal at this time should be to use a combination of medications, such as a dopamine agonist with levodopa, in order to allow for a lower dose of levodopa, which reduces the risk of developing motor fluctuations.

Younger patients may find it difficult to accept that their bodies may at times be stiffer, slower, or shakier; they may want to be completely rid of all symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, and will often request more medication to do so. But it is important to accept the presence of some Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms that stem from taking less medication, in order to avoid some of the immediate and long-term side effects of taking more medication. YOPD patients also need to watch carefully for cognitive side effects from the medications, such as mental dulling or daytime sleepiness, as most young-onset patients are actively employed and need to remain particularly alert.

Another factor to consider in the treatment of YOPD persons is the possible need for surgical therapy. When a 32-year-old is diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, ten years later, at age 42, he or she still has a long life to lead, compared to a 75-year-old, who will likely have adequate control of the Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms for the remainder of his or her life. If the YOPD person develops disabling motor fluctuations and if the motor symptoms are not as well controlled by the medications, surgical treatments can offer tremendous improvement in daily motor function and a return to independence.

Sherry was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at age 38, and she has found that surgery was a tremendous help to her:

After only eight years of having Parkinson’s disease, I decided to have deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery. I felt so helpless because I had horrible dyskinesia where my arms and legs would wiggle nonstop, sometimes all day. If I lowered the dose of my medicine, then I was so slow I couldn’t even get up off the couch or walk or swallow. It’s almost a year since my last surgery. I had an electrode put into the right side of my brain first and six months later I had another electrode put into the left side. It was the best decision I ever made. I am about 70 percent improved, with almost no dyskinesia. I can do almost everything for myself again.

Coping with Young-Onset Parkinson’s Disease

Being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at a younger age can seem catastrophic. It is very common for a younger person to be in shock and often in denial after receiving such news. But its important to be patient with yourself, and realize that Parkinson’s disease is not a death sentence, nor the end of your world. You will survive, and you too will have your stories to share.

Alan remembers when he was diagnosed at age 38, 30 years ago:

If I could have seen into the future to today, I would have felt a lot better when my doctor told me I had Parkinson’s disease. I have had tremors and slowness and dyskinesia for a long time, but I can still walk and pretty much take care of myself; my wife helps me with buttoning and getting up out of bed before my medication kicks in. I have seen people who are much worse than me, and I think I am lucky. After thirty years of Parkinson’s disease, I’m not afraid of it or what my future holds. I’m just glad to still be here.

Probably the most prominent young-onset Parkinson’s disease patient in the United States, actor Michael J. Fox, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 1991, at age 30. Fox, who has formed a foundation to search for a cure, has become a visible figure in the struggle for greater awareness of Parkinson’s. But Fox’s approach to coping with the condition is that he refuses to be defined by it. Instead he said he’s been enhanced by it, describing himself as a “fuller person.” Says Fox: “I’m living with it. And it is okay. I’m still me—me with Parkinson’s.”

Mary Noone, a Glenwood Springs, Colorado, artist whose Parkinson’s disease appeared nine years ago, at age 37, feels that it is important for young-onset Parkinson’s patients to be upfront about having the condition.

I tell everybody I have it, because it makes me uncomfortable to be shaking. People have even thought I was drinking, et cetera, so I think it’s best to be very honest with your friends, family, and people you come into contact with. Ultimately, the more you get the information out there, the more chance there is that somebody is going to come back with an answer.

The impact on your career and family can also be a concern. There are so many questions a newly diagnosed YOPD patient is likely to ask: How long will I be able to work? Will I have to change the kind of work I do? What is my disability insurance? How will this affect my marriage, our retirement plan, the children’s college? These are very valid and real concerns. Each person is different, with a different career or job, different stages and symptoms of Parkinson’s, different financial and family resources, and different needs and goals. Learning how to adapt and change as life and health changes becomes an important skill.

Susie, a 48-year-old former pediatric intensive care unit nurse, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at age 32.

I did well for the first seven or eight years after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. I did have to take my medication on a strict schedule every four hours and often had to take an extra Sinemet pill while I was at work to get an extra boost so I could write and use my hands. I talked to my employer early on about Parkinsons disease, and they were wonderful and really worked with me; after four years I changed from a twelve-hour shift to an eighthour one, which really helped. After eight years it became more difficult to keep up with the demands of ICU nursing; I was more fatigued and had more difficulty with writing and using needles, so I changed to nursing education part-time and am receiving partial medical disability. The best thing for me was to have a compassionate and understanding boss and coworkers.

Success Tips for YOPD Patients

• Talk about your illness with someone you trust early on. Don’t go it alone!

• Consider seeing a professional counselor. Dealing with a serious illness at a young age can be extremely painful emotionally and psychologically, and your family may be struggling along beside you and not able to offer you the advice and understanding that you need.

• Find a young-age support group, and if one is not available, talk to other YOPD patients and try to start one; this can be an informal social gathering or an organized educational forum. Make it what you want and need it to be, and let it evolve over time. Discussing your particular needs, frustrations, and coping strategies regarding Parkinson’s disease with other young patients can be an uplifting and freeing experience. https://www.facebook.com/groups/269825817156695/

• Find a doctor who specializes in Parkinson’s disease.

• Educate yourself (get a newsletter, buy a book, get online). Knowledge is power!

• Exercise, exercise, exercise!

• When you are ready, consider talking to your employer about your health to involve them in any possible changes in your duties at work and to plan for the future.

• If you are really struggling with performing your work duties, discuss this with your employer and your doctor to seek solutions with their help.

• Meet with a financial advisor and review your life, health, disability, and retirement plans.

• Consider marriage or couples counseling to help develop relationship strategies for coping with the disease.