Chronic Pain Syndrome

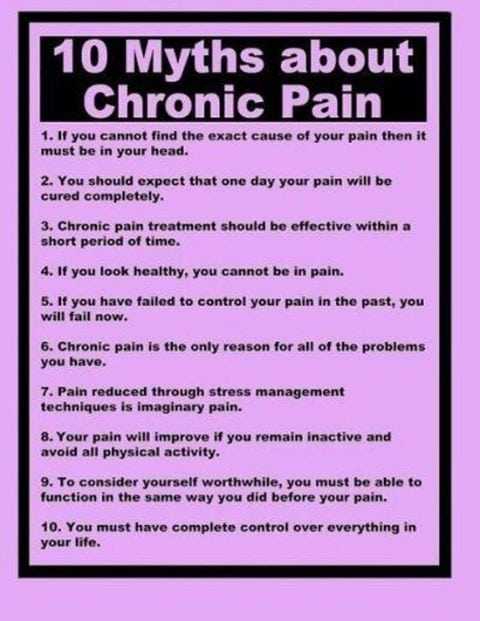

In chronic pain syndrome, a patient has pain that has persisted months or years longer than one might expect from an inciting event. Several maladaptive features are associated with the pain. In patients with chronic pain syndrome, suffering occurs at every level of being: physical, emotional, mental, social, and spiritual. In essence, the patient becomes defined by pain rather than by a more soulful sense of self. Chronic pain syndrome may be seen as a combination of any of the other clinical syndromes discussed previously. Chronic pain syndrome may be one of the most challenging clinical syndromes for clinicians to address and manage.

Chronic pain syndrome entails chronic neuropathic pain and, as such, represents a dysfunction of the nervous system. There is no clear consensus as to why patients develop chronic pain syndrome. What is clear is that an inciting event or events occur, and patients seemingly never recover. Rather, pain persists, takes on a life of its own, and the patient becomes imprisoned, living a life of pain every waking moment.

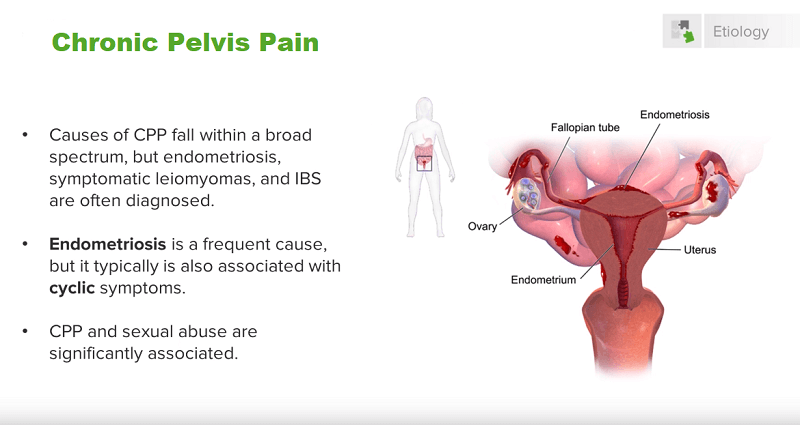

Chronic pain syndrome can develop in any region of the body. Some patients have chronic, refractory headache. Others have chronic, refractory neck pain. Others have unrelenting low back pain. Others have more diffuse body and joint pain. Chronic pain syndrome is distinguished from the chronic pain that occurs as a result of inflammatory or mechanical causes by the fact that no situational fluctuations to the pain occur. Chronic pain syndrome is essentially indistinguishable from post-laminectomy syndrome if the patient has undergone lumbar spine surgery.

Patients who have chronic pain syndrome in the region of the lower back typically have pain that never ceases. Patients have difficulty sleeping at night because of pain. Pain may be described as sharp, burning, electric, shock-like, lancinating, achy, or simply as a diffuse, deep-seated pain. Sensitivity to touch may be present in the region of the pain.

Sometimes, associated autonomic features are present, in that there may be alterations in skin color or temperature and even regional changes in the hair growth pattern. Because of musculoskeletal disuse, bone loss may develop. In addition, muscle contractures and even bony contractures can occur. In women of childbearing age with chronic pain syndrome, menstrual irregularity is common.

Patients generally complain that pain worsens with any type of prolonged activity, and pain also is present at rest. Weather fluctuations may influence pain, and day-to-day emotional fluctuations may precipitate pain. Typically, patients have undergone numerous therapeutic interventions, including epidural injections, facet blocks, surgical procedures, multiple trials of medications, and multiple trials of physical therapy and spinal manipulation.

Depression is the rule in patients with chronic pain syndrome. Often, patients have a flat affect , which means that they no longer express a range of emotions when speaking. Many patients have lost a sense of hope. Relationships have become defined by pain, and the family unit often is dysfunctional because the patient suffering with pain can no longer become meaningfully engaged in family or social relationships. Very often, patients are out of work and receiving disability compensation.

Patients often feel desperate, and they may have sought a multitude of alternative treatment strategies. Too often, patients have been taken advantage of by clinicians who offer unrealistic hope. Many patients with chronic pain syndrome seem to be going through the motions when they are undergoing an evaluation by a clinician, because they feel that they are not being heard; very often, they think that no one believes them. This is not surprising given the fact that multiple treatments have failed and, very often, clinicians will simply say that no adequate explanation exists for the patient’s pain, thus suggesting that the pain must have a psychosomatic origin.

Cause of Chronic Pain Syndrome

The cause of chronic pain lies within nervous system dysfunction. A concept in neuroscience called brain plasticity means that the brain can reorganize following an insult to the body or nervous system. There is no question that brain reorganization occurs in chronic pain patients, but the reorganization is not necessarily because of a lesion in the nervous system. Rather, the reorganization occurs as a result of a multitude of physical and emotional responses to a major inciting event or multiple inciting events.

Genetic factors may predispose to the development of chronic pain syndrome. Some studies suggest genetic alterations in pain receptors of the spinal cord, and these alterations predispose such patients to neuropathic pain. Other evidence suggests that patients who have suffered prior trauma or abuse are more predisposed to developing chronic pain syndrome when compared with the general population. This latter explanation should not lead physicians to presume that patients with chronic pain syndrome have been prior victims of abuse.

Even in patients who suffer with chronic pain syndrome, fluctuations in pain may occur that have an anatomic basis. Thus, clinicians must always be aware of this possibility. For example, a patient suffering with chronic pain syndrome may develop a superimposed lumbar disc herniation, a severe strain in the iliopsoas muscle, or an acute spinal fracture, all as a result of prior, chronic maladaptations. Any one of a number of possibilities of more acute, anatomically based pain is possible in patients who suffer with chronic pain. Addressing these factors is key, while keeping in mind that they are only one part of the larger cycle of pain.

Physical Examination

No classic physical examination findings are present in patients who suffer with chronic pain. More often than not, several maladaptive musculoskeletal findings are evident when performing a careful physical examination. This may include abnormal movements of the lumbar spine in flexion and extension, abnormal contractility of supporting lumbar spine musculature, or chronic spasm and sensitivity of muscles, which can be noted by palpation. The neurologic exam is unremarkable unless the chronic pain syndrome has developed in the setting of a prior neurologic insult, for example, a nerve root injury as part of a lumbar spine disorder.

Imaging and Diagnostic Studies

No classic imaging and diagnostic studies are definitive in patients who suffer with chronic pain syndrome. Some evidence may be present of prior surgical interventions and, as with patients who suffer with failed-back syndrome, incidental findings of degenerative disc changes or chronic disc herniations may be noted. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies may show evidence of chronic lumbar nerve root irritation, but do not reveal meaningful active denervation changes. Very often, patients are subjected to a multitude of imaging and diagnostic studies, including but not limited to multiple plain radiographs, multiple magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, routine and triple phase bone scan studies, EMG and nerve conduction studies, myelogram, and detailed rheumatologic evaluation. None of these studies provides a compelling explanation for the patient’s pain.

In functional brain imaging studies, such as functional brain MRI or positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, patients who suffer with chronic pain syndrome may demonstrate abnormal metabolism and hyper-responsiveness in several areas of the limbic brain , which is the largely nonconscious, emotional brain. These studies demonstrate that the simplistic view of pain pathways no longer holds for patients with chronic pain syndrome.

Treatment Considerations

Nonsurgical

Patients with chronic pain syndrome benefit from psychological counseling. However, the manner in which this is presented to the patient is important. Patients should not be led to believe that they are undergoing psychological counseling because their pain is psychogenic in origin. Rather, patients require psychological counseling because an almost universal, coexisting depression and sense of hopelessness are present. Coping strategies are usually poor, and the family unit often has broken down. Individual psychological counseling in conjunction with group therapy is extremely beneficial.

Medication management usually includes a combination approach. Because patients frequently have a disruption of their sleep cycle, medications such as amitriptyline (an early-generation antidepressant medication) or an anticonvulsant with sedative properties can be useful to help restore sleep. Low-dose amitriptyline may have painrelieving properties in and of itself. Similarly, anticonvulsants should be titrated upward, as tolerated and needed, because they may provide an important avenue of pain relief.

Newer-generation antidepressants also may play an important role in helping to treat depression and anxiety. Narcotic analgesics may be an important part of treatment, because anything that leads to pain reduction may help to improve quality of life. Muscle relaxants also may play an important role in patients who have chronic, hypercontracted musculature. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have little role in the longterm management of chronic pain syndrome.

Manual therapy plays an extremely important role. However, such therapy must be performed with a long-term vision in mind. Most patients have already been through multiple attempts at physical therapy or chiropractic care. Manual therapy should be performed with a focus on myofascial release and craniosacral technique, in an attempt to help the patient turn inward, become more attuned to his body, and to gradually help restore proper posture in body mechanics.

Therapeutic injections may or may not play a role, depending on the clinical manifestation at hand. Some patients who suffer with chronic pain syndrome also have situational, mechanical pain. For example, some patients with chronic low back pain also develop more specific facet jamming; such patients may obtain some relief from facet injections. However, if such injections are utilized, it should be understood that they are not the answer, but only a small part of the multidisciplinary treatment. If patients obtain meaningful benefit, then a facet rhizotomy procedure should be considered. Usually, epidural corticosteroid injections or selective nerve root injections are ineffective.

Once patients have developed some aspects of pain control and coping strategies, a gentle exercise program should be encouraged. This should be coordinated carefully with the physical therapist.

Surgical

One must proceed very cautiously with any thoughts of surgerv in patients who suffer with chronic pain syndrome. Patients are often desperate, and even physicians can be desperate to try to cure the patient of his malady. It is important to remember that chronic pain syndrome represents a dysfunction of the nervous system, and surgical interventions to correct anatomic lesions or deficits may only lead to an augmented pain response postoperatively. Unless a clearly defined, anatomically well-localized cause of one aspect of the patient’s chronic pain syndrome exists, all surgical considerations should be avoided. Physicians should explain to patients that surgery may only worsen the situation.

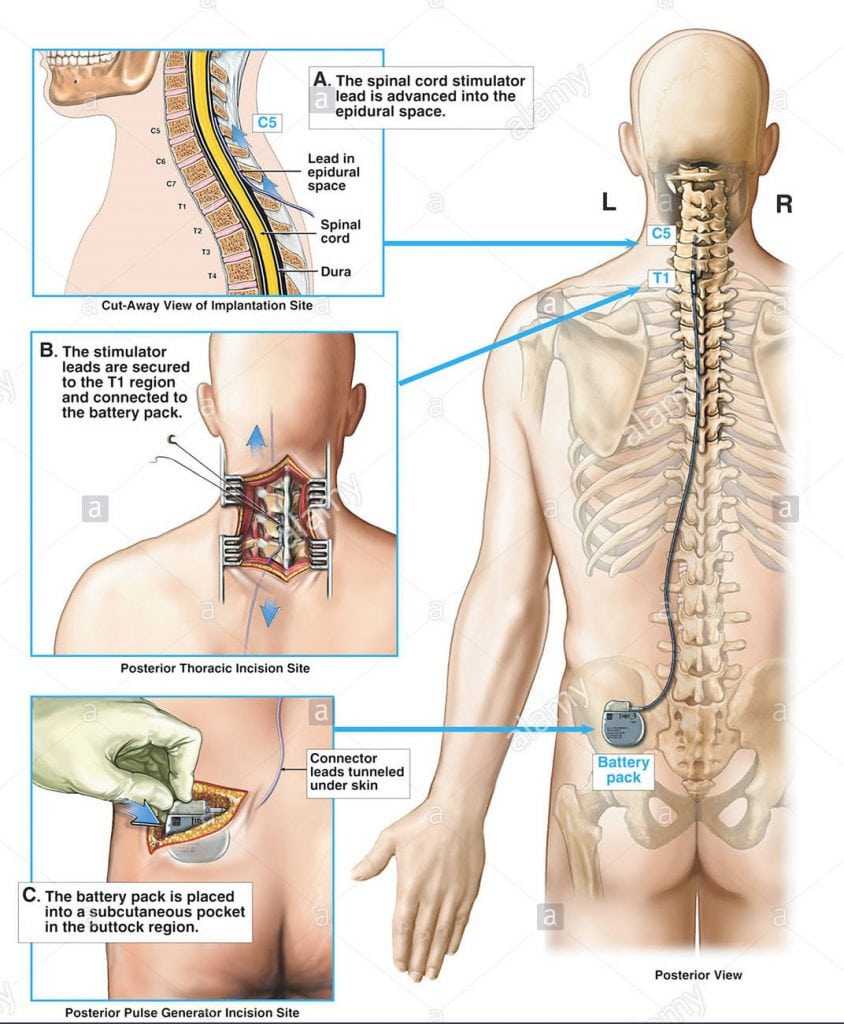

In cases of well-localized pain, spinal cord stimulator may be considered as part of a welldisciplined, multidisciplinary treatment. Again, the lure may be that spinal cord stimulator will alleviate the patient’s problem; this is unlikely in patients who have chronic pain syndrome. If spinal cord stimulator can help to alleviate some pain, and if patients can achieve better coping strategies and obtain a better sense of pain relief with medication management and manual interventions, then such an intervention can be considered.

In patients who clearly benefit from narcotic analgesics, but who cannot tolerate systemic side effects, then a morphine pump may be considered. As with a spinal cord stimulator, this should be part of a multidisciplinary approach, not a unilateral intervention.

Mind-Body Considerations

Mind-body considerations play a pivotal role in managing patients with chronic pain syndrome. Such a patient has been suffering considerably, usually with a marked dissociation between the patient’s emotions and his sense of physical pain. Initial mindbody approaches should include meditation and relaxation exercises, possibly coupled with biofeedback or similar strategies. At a minimum, such strategies should help the patient cope and gain a sense of control over his own physiology and pain responses. Sometimes, such interventions open the door to greater mind-body insights.

The one potential trap of mind-body therapy in treating patients with chronic pain syndrome is the assumption that the patient is hiding something from his past. This is a dangerous assumption in which a patient is led to believe that he is the cause of his problem. Although we can assume that depression, anxiety, and pain intermix with chronic pain syndrome, we cannot presume that depression or prior psychological factors are the sole cause of chronic pain syndrome.

Summary Points

- Chronic pain syndrome can develop from any one of a number of clinical syndromes. In essence, every aspect of the patient becomes defined by pain.

- Patients with chronic pain syndrome are universally depressed, and a high incidence of breakdown in the family and social structure is present.

- Functional brain imaging studies of patients with chronic pain syndrome may reveal abnormalities in parts of the brain that mediate nonconscious emotions.

- There may be genetic predispositions to chronic pain syndrome, and there may also be a history of prior personal, emotional, or physical abuse. However, many patients have neither of these predispositions, and such predispositions should never be assumed.

- Treatment for chronic pain syndrome should be multidisciplinary, including individual and group psychological counseling when possible.

- Treatment should be long term; at any point in time, the treatment may change considerably, based on patient-clinician results and experiences.